The Tragic Day 60 Bombers Fell Before the P-51s Could Save Them

YouTube / No Man's Land

Prelude to Black Thursday

On October 14, 1943, the Eighth Air Force sent 291 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses from England to destroy ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt, Bavaria. These plants supplied almost half of Germany’s entire output, making them a critical target. Allied planners believed that crippling this production could reduce German war output by nearly one-third within months. But the mission, remembered as “Black Thursday,” became one of the costliest in American air history—60 bombers lost, 17 damaged beyond repair, and 600 men killed, wounded, or captured.

The Schweinfurt raids were part of the Allied strategy born from the “industrial web theory,” which taught that destroying key parts of an enemy’s industrial system could cripple its entire war machine. Ball bearings were viewed as the perfect bottleneck—impossible to stockpile and vital to nearly every weapon. However, the Americans underestimated the dangers of deep, unescorted bombing missions over heavily defended territory.

The Strategic Gamble

Earlier that August, a raid on Schweinfurt and Regensburg had already shown the deadly cost of these missions, with more than a quarter of the bombers lost. The key problem was range. The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt escorts could only reach the edge of Germany, leaving the bombers unprotected for almost 200 miles. That gap gave German fighter forces time to organize fierce counterattacks.

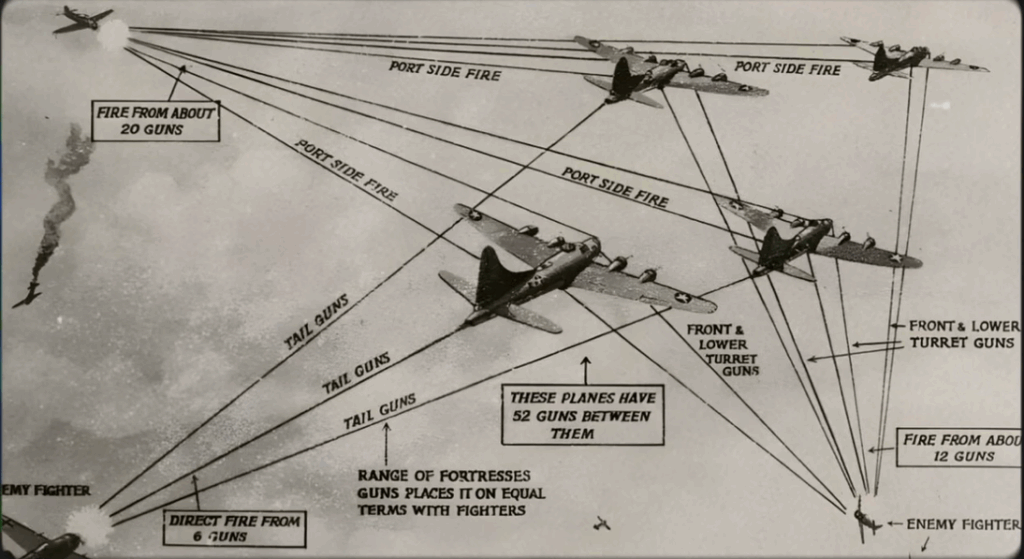

By October 1943, German air defenses had evolved into a precise network. Radar sites tracked incoming aircraft from over 100 miles away and directed fighters into well-coordinated attacks. Tactics like head-on passes exploited the B-17’s weakest defensive points. Despite their heavy armament—13 machine guns per plane—the bombers could not match the speed or firepower of interceptors like the Fw 190.

The Battle Over Bavaria

That morning, weather promised clear skies for visual bombing, and the formations lifted off despite reports of nearly 900 enemy fighters ready for defense. Around 10:10 a.m., the first German interceptors appeared, and once the P-47 escorts turned back, the bombers faced a three-hour onslaught. Survivors recalled the sky filled with white puffs from cannon shells and burning aircraft spiraling down.

Each B-17 carried thousands of gallons of fuel and oxygen at 25,000 feet—one hit could ignite the aircraft instantly. Still, under Major John Kidd’s leadership, formations stayed tight to maximize defensive fire. When the bombers finally reached Schweinfurt, they dropped over half a million kilograms of explosives with remarkable accuracy, striking several key factory buildings.

Losses and Lessons

The cost, however, was devastating. Sixty bombers never returned, and hundreds of airmen were gone. The Americans realized that courage and formation flying were not enough against a coordinated defense. German losses were comparatively light—about 38 fighters destroyed.

Strategically, the raid forced Germany to disperse ball-bearing production into smaller facilities, lowering efficiency and stretching its resources. But for the Americans, it was clear that daylight bombing without long-range escort was unsustainable.

A Turning Point in Air Warfare

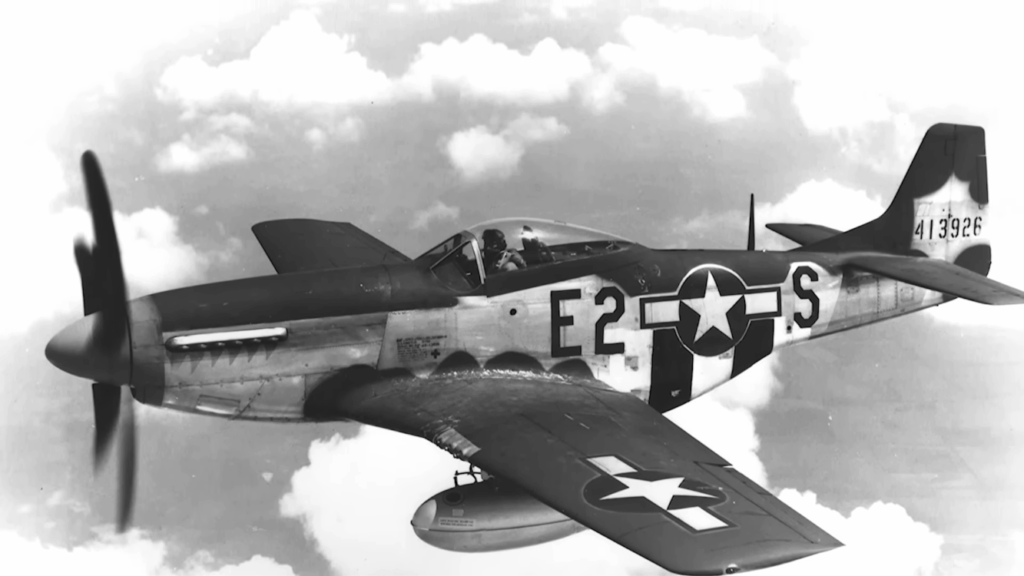

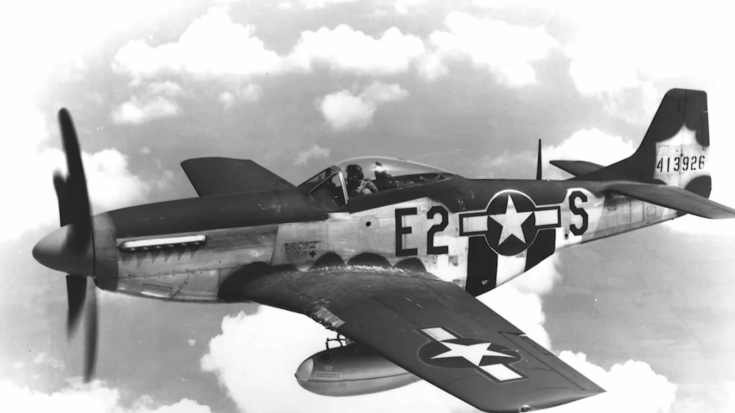

The solution arrived months later with the P-51 Mustang, whose extended range finally allowed bombers full escort to Berlin and back. The lesson from Black Thursday reshaped air strategy: bombers alone could not survive without fighter protection.

General Curtis LeMay summarized it plainly—bravery was not enough; superiority in numbers, tactics, or technology was essential. The 600 airmen lost that day paid the price for a truth that changed the course of air warfare forever.