The Story of the Day America Wiped Out 400 Japanese Planes in a Single Strike

The Lost Record / YouTube

The Turning Tide in the Pacific

By the summer of 1944, the war in the Pacific had reached a crucial stage. For nearly three years, Japan had fought to expand and hold its empire, but its early victories were slipping away. After defeats at Midway and Guadalcanal, and the loss of shipping to American submarines, Japan’s naval strength began to crumble. Meanwhile, the United States was producing ships, aircraft, and weapons at a pace Japan could never match. The islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam—the Marianas—became Japan’s last outer defense. If they fell, American B-29 bombers would be within range of Tokyo.

Japan knew the stakes. Losing the Marianas would expose the homeland and cut vital supply lines. As the U.S. Fifth Fleet under Admiral Raymond Spruance advanced across the Pacific, Japan’s commanders prepared for one last gamble. They believed a single, massive naval battle could change the outcome of the war. On June 15, 1944, American troops landed on Saipan, beginning Operation Forager. The invasion met fierce resistance from entrenched defenders, but behind the men on the beaches stood the immense power of Task Force 58, commanded by Admiral Marc Mitscher—fifteen carriers carrying hundreds of aircraft, ready to dominate the skies.

Japan’s Desperate Gamble

The invasion of Saipan sent alarm through Tokyo. Japan activated Operation A-Go, its plan to destroy the U.S. fleet in a decisive battle. Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa led a massive fleet of nine carriers, five battleships, and over 400 aircraft. On paper, it was still an impressive force. Carriers such as Shokaku, Zuikaku, Taiho, and Junyo represented the last of Japan’s carrier power. Yet the truth behind these numbers was grim.

Most of Japan’s veteran pilots—those who had fought at Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, and Midway—were gone. Their replacements were young, hastily trained, and often barely capable of landing on a carrier deck. Many had fewer than 100 hours of flight experience. Their planes, mainly Mitsubishi Zeros, were still agile but lightly built, lacking armor or self-sealing fuel tanks. Facing them were the rugged American F6F Hellcats—fast, durable, and guided by radar control that directed them straight toward incoming enemy formations. Japan’s fleet was betting on courage and numbers to defeat technology and experience.

The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot

At dawn on June 19, 1944, Ozawa launched his attack. More than 400 Japanese planes took off in four waves, heading across 200 miles of ocean toward Task Force 58. Their mission was to destroy the U.S. carriers and halt the invasion of Saipan. But the Americans were ready. Radar-equipped picket ships detected the approaching aircraft long before they were visible. Fighter directors sent squadrons of Hellcats into the air to intercept them.

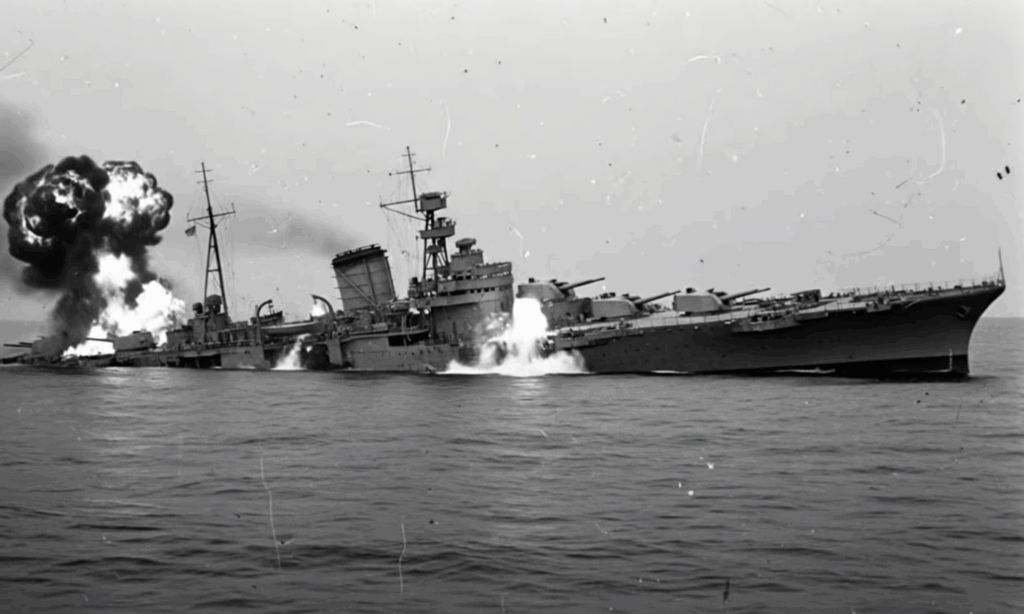

The result was disastrous for Japan. Hellcats tore through the incoming formations with deadly precision. American pilots later described the scene as a “turkey shoot.” Zeros and dive bombers burst into flames, spiraling into the sea. Only a handful broke through to attack the carriers, causing little damage. By midday, nearly 250 Japanese planes had been destroyed. In one day, Japan’s air superiority vanished.

The Submarine Strikes

While the skies were filled with dogfights, American submarines waited below. The USS Albacore sighted Ozawa’s flagship, the carrier Taiho, and fired torpedoes that struck deep in her hull. At first, her crew thought she could be saved, but leaking gasoline fumes ignited hours later, causing a massive explosion that sank her. Around the same time, the USS Cavalla attacked Shokaku, scoring three torpedo hits. The great carrier erupted in flames and sank with over a thousand men aboard.

These losses crippled Ozawa’s command structure. His fleet was scattered, communications were breaking down, and most of his aircraft were already gone. By nightfall, the once-formidable mobile fleet was in chaos.

The Final Blow

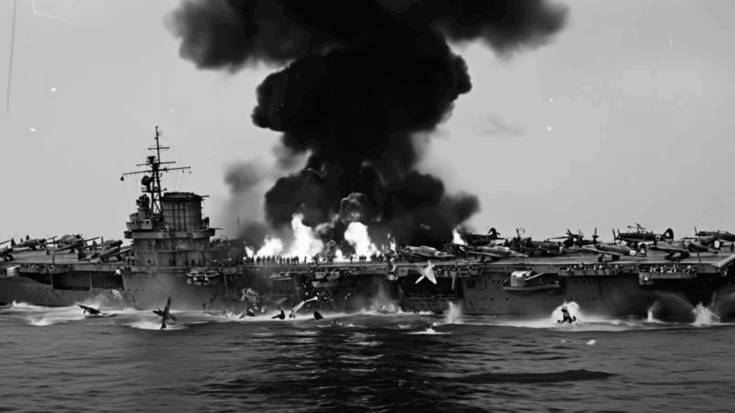

The next day, June 20, American scouts located the retreating Japanese fleet more than 300 miles away. Despite fading light and the long distance, Admiral Mitscher ordered a massive strike—over 200 aircraft launched from U.S. carriers. The American pilots found their targets just before sunset. Bombs and torpedoes struck the light carrier Hiyo, which exploded and sank. Other carriers, including Zuikaku and Chiyoda, were heavily damaged. Japanese air resistance was weak and uncoordinated.

As darkness fell, many American planes ran low on fuel, forcing Mitscher to take a risky decision. He ordered all U.S. carriers to turn on their lights—an unprecedented move in wartime—to guide the returning pilots home. Many still ditched at sea, but hundreds were saved.

By the end of June 20, Japan had lost three carriers—Taiho, Shokaku, and Hiyo—and more than 400 aircraft. Nearly all of its remaining trained pilots were dead. The U.S. lost about 130 planes, mostly from fuel exhaustion. Japan’s once-mighty carrier fleet was left helpless, its decks empty and its air wings destroyed. The battle, later known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, marked the end of Japan’s carrier power and the moment when American control of the Pacific skies became absolute.