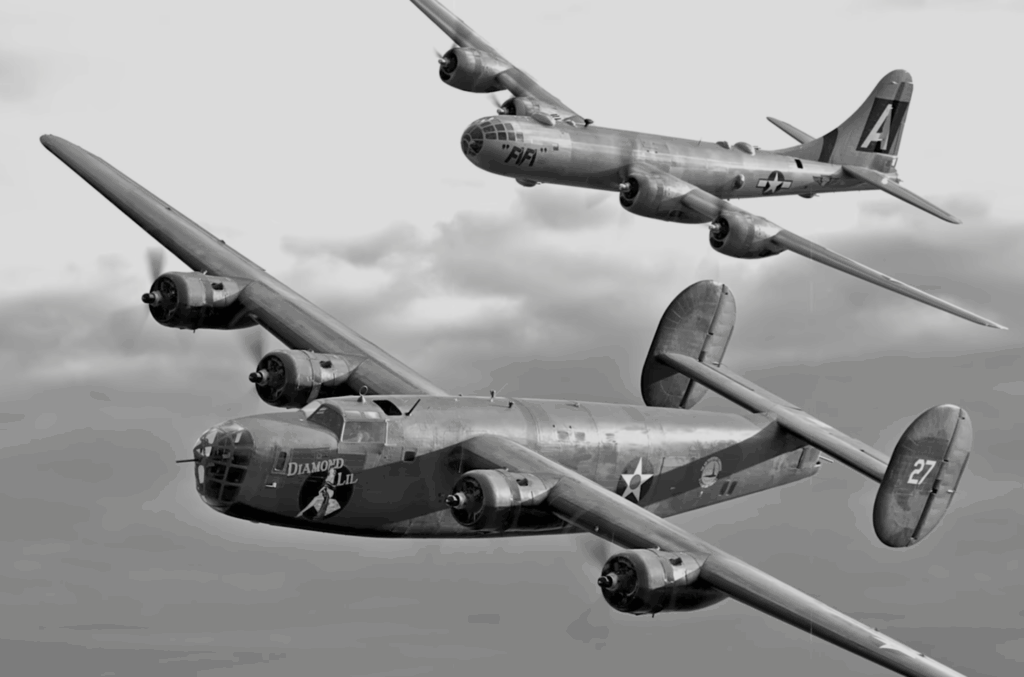

Why the B-24’s Flawed Wing Design Put Thousands of WWII Planes at Risk

Vintage Planes / YouTube

A Bomber Built for Distance

When the United States prepared for global war in 1938, military planners faced a serious problem. The Boeing B-17 could not fly far enough to hit key industrial targets in Germany or reach the long distances needed in the Pacific. General Henry “Hap” Arnold demanded a bomber with greater speed, higher altitude, and far longer range. Consolidated Aircraft offered a bold answer. Instead of simply producing more B-17s, the company proposed an entirely new design. Engineers promised a bomber that would outfly the B-17 in every measure and be ready for production in record time.

Their proposal became the B-24 Liberator. Central to the plan was a radical “Davis wing,” a high-aspect-ratio airfoil created by self-taught designer David R. Davis. Wind-tunnel tests showed that this thin, long wing reduced drag and extended range by nearly a quarter compared to the B-17. With a projected top speed over 270 miles per hour and a range approaching 3,000 miles, the new bomber looked like the future of American air power. But the same feature that gave the B-24 its reach also introduced hidden dangers.

Strength Traded for Efficiency

The Davis wing achieved its performance by using a very slim structure. Fuel tanks were built directly into the wing’s skin, which was less than a tenth of an inch thick in places. This saved weight and space, but it also meant that even minor damage could cause leaks or fires. The wing’s narrow design required higher stall speeds, forcing pilots to keep the aircraft fast during takeoff and landing. In rough weather or when hit by enemy fire, the wing could twist violently, leaving almost no safety margin.

Flight tests confirmed both promise and peril. The prototype easily outperformed the B-17, yet engineers warned of structural weakness. Pilots discovered that the B-24 demanded precise handling. Landing speeds exceeded 100 miles per hour, and a sudden loss of lift could send the plane into an unrecoverable spin. Training accidents soon followed, and crews quietly nicknamed the bomber the “Widow Maker.”

Production Wins Over Caution

Despite these concerns, officials in Washington pushed for mass production. The B-24 could be built faster than the B-17, especially once Ford’s massive Willow Run plant joined the effort. In a war where output meant victory, speed of manufacture outweighed the risks. By the end of the conflict, American factories had produced more than 18,000 Liberators, making it the most numerous U.S. military aircraft of the war.

Combat experience showed the tradeoffs clearly. The B-24 could fly farther and carry heavier loads than the B-17, striking oil refineries in Romania and patrolling the Atlantic to hunt German submarines. But it also suffered higher accident and loss rates. Crews respected its abilities yet remained wary of its handling and the vulnerability of its thin fuel-filled wings.

Legacy of a Dangerous Innovation

The Davis wing never became a model for later bombers. Its laminar-flow advantages worked only under perfect conditions, and even small dents or ice destroyed the effect. Postwar designs borrowed lessons but avoided the B-24’s extreme compromises. Still, the Liberator’s record speaks to its strategic value. It delivered a larger share of U.S. bomb tonnage than any other American bomber and helped close the mid-Atlantic “gap” that once sheltered German submarines.

The B-24 proved that innovation can win wars while exposing those who fly to grave risks. Its wing gave the Allies global reach but demanded constant vigilance from every crew that climbed aboard.