The Tragic Reason So Many B-24 Liberator Crews Didn’t Return from WWII Missions

Voices From the Front / YouTube

The Flying Coffin

More than 30,000 young men climbed into the B-24 Liberator bomber during World War II and never returned. Entire towns lost sons in the skies, all tied to one aircraft that was meant to be a miracle of modern engineering. On paper, the B-24 seemed unbeatable—fast, far-flying, and capable of carrying more bombs than any other Allied aircraft. But in reality, it became one of the most dangerous planes ever flown by Allied crews.

In 1939, the U.S. Army Air Corps wanted a bomber that could fly farther, faster, and carry heavier loads than the famous B-17 Flying Fortress. The Consolidated Aircraft Company responded with an ambitious new design called the Model 32, soon renamed the B-24 Liberator. It featured sleek, high-lift wings, a deep fuselage, and four powerful engines that gave it an impressive range of 2,000 miles and the ability to haul up to 12,000 pounds of bombs. At its production peak, one B-24 rolled off the assembly line every hour, with more than 18,000 built—more than any other heavy bomber in history.

Into Combat

The B-24 entered combat in early 1942 with the Royal Air Force, flying long-range patrols over the Atlantic Ocean. Its reach helped close the “air gap” that German submarines had exploited to attack Allied convoys. Soon, American B-24s joined the fight from bases in England, North Africa, and Italy.

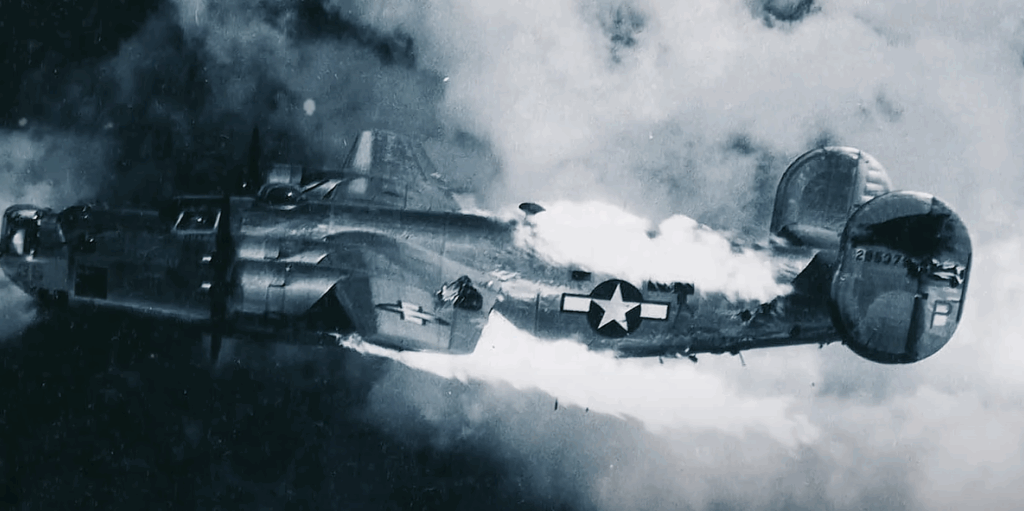

When flown alongside B-17 formations, the differences between the two aircraft quickly became clear. The B-24 was faster and flew at lower altitudes, forcing it to separate from B-17 groups during missions. That separation made it harder to defend against German fighters and anti-aircraft fire. Losses mounted quickly, as formations of Liberators were ripped apart midair. In some cases, German forces even flew captured B-24s to sneak into Allied formations, causing deadly confusion.

A Dangerous Design

Flying the B-24 was exhausting and physically demanding. Its control systems were heavy, forcing pilots to swap positions every 15 minutes to avoid fatigue. The plane struggled to stay in formation, drifting constantly and forcing crews to battle the controls while under fire.

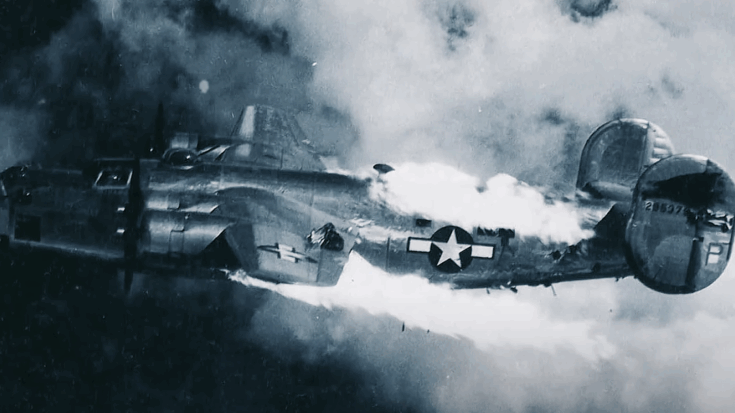

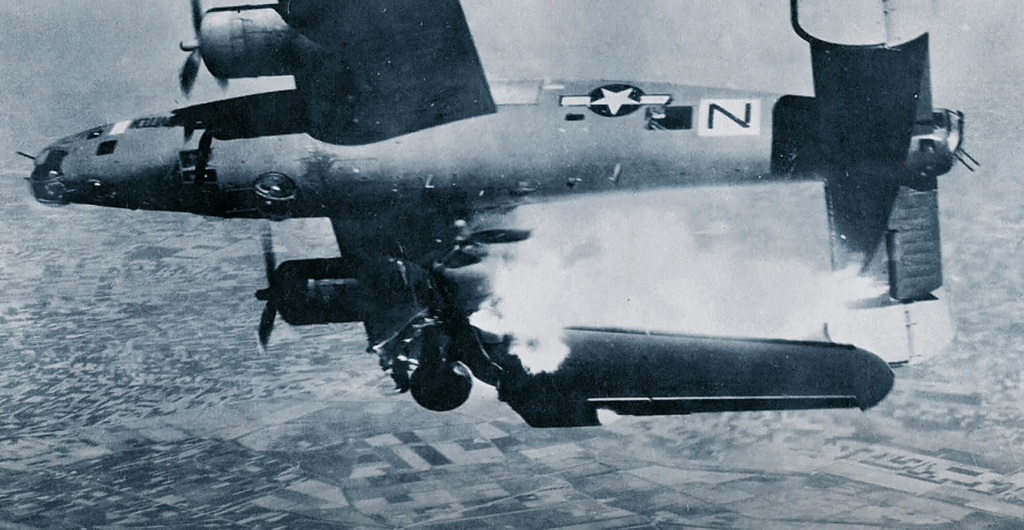

The Liberator’s thin armor and weak fuel tanks made it extremely vulnerable. A single flak burst could rip through its lightweight wings, while its self-sealing tanks often failed to prevent fires. Inside, the design posed deadly hazards. A narrow nine-inch catwalk ran through the bomb bay—the only passage between crew sections. Emergency exits were cramped and awkwardly placed, making escape almost impossible in a spinning or burning aircraft. If forced to ditch at sea, the flat-bottomed fuselage hit the water so hard that the plane often sank instantly, trapping men inside.

Operation Tidal Wave

On August 1, 1943, one of the most tragic missions in bomber history took place. Operation Tidal Wave was meant to cripple Germany’s fuel supply by destroying oil refineries in Ploiești, Romania. A total of 178 B-24s took off from Libya in total secrecy. But German intelligence already knew they were coming.

Before even reaching the target, disaster struck when a lead bomber crashed into the sea, killing the navigation leader. Clouds scattered the formation, and by the time the bombers reached the city, defenses were ready. They flew only 250 feet above the ground—low enough to evade radar but directly into anti-aircraft fire. Flak, machine guns, and fighter planes tore through them. Bombers exploded midair, collided, or slammed into buildings. One was hit head-on by an 88mm shell and crashed into the gun that fired it. Another went down in a city prison, killing more than 50 civilians.

Aftermath and Legacy

The few surviving crews tried to escape the burning skies, but enemy fighters pursued them relentlessly. Many planes went down across Romania and the Mediterranean. By the end, 73 bombers were lost, over 500 airmen were dead or wounded, and 100 were captured. The oil refineries were quickly repaired, and the mission changed little about Germany’s fuel situation.

Still, the Liberator crews continued to fly. They bombed rail lines, factories, and military targets across Europe and later dropped food to civilians in the Netherlands. But the price never stopped rising. By 1945, more than 30,000 men who had flown aboard the B-24 were gone. And when the war ended, the aircraft that had once filled Allied skies vanished almost overnight—scrapped and melted down, leaving behind only stories of courage, loss, and the heavy price of war.