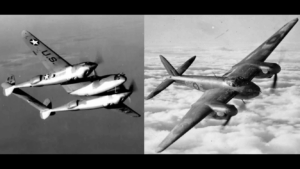

The Story of How B-25 Gun Noses Shattered Japanese Warships in WWII

The War Files / YouTube

The Rise of a Deadly Weapon

By 1943, Japanese naval officers realized that moving supplies in daylight had become almost impossible within range of American B-25 bombers. What had once been routine convoys carrying food, ammunition, and reinforcements across the Pacific now turned into deadly missions. Even small ships risked being destroyed, and larger vessels had no chance once bombers appeared overhead. Desperate to adapt, Japanese commanders shifted to using destroyers and submarines at night. Yet these efforts could not replace the vast cargo capacity of freighters, and isolated garrisons began to starve.

A clear example came at Lae in New Guinea. On March 3, 1943, a convoy carrying supplies for thousands of troops was annihilated before reaching shore. Months later, the men who survived the battle were forced to retreat through jungles, where disease, exhaustion, and hunger claimed many lives. The inability to protect shipping showed how devastating the B-25 had become when flown at low level with forward-firing guns blazing.

Countermeasures that Failed

Japanese defenses struggled to cope. Fighters had difficulty intercepting B-25s, which attacked too low and too fast. Heavy anti-aircraft guns designed to hit high-altitude bombers were almost useless against strafers roaring at treetop level. In moments of desperation, some Japanese pilots even attempted to ram the bombers, sacrificing their own aircraft in hopes of bringing one down. Despite such efforts, losses mounted. By mid-1944, more than sixty percent of Japan’s shipping tonnage had been destroyed, much of it by B-25 skip bombing attacks that turned ships into flaming wrecks in minutes.

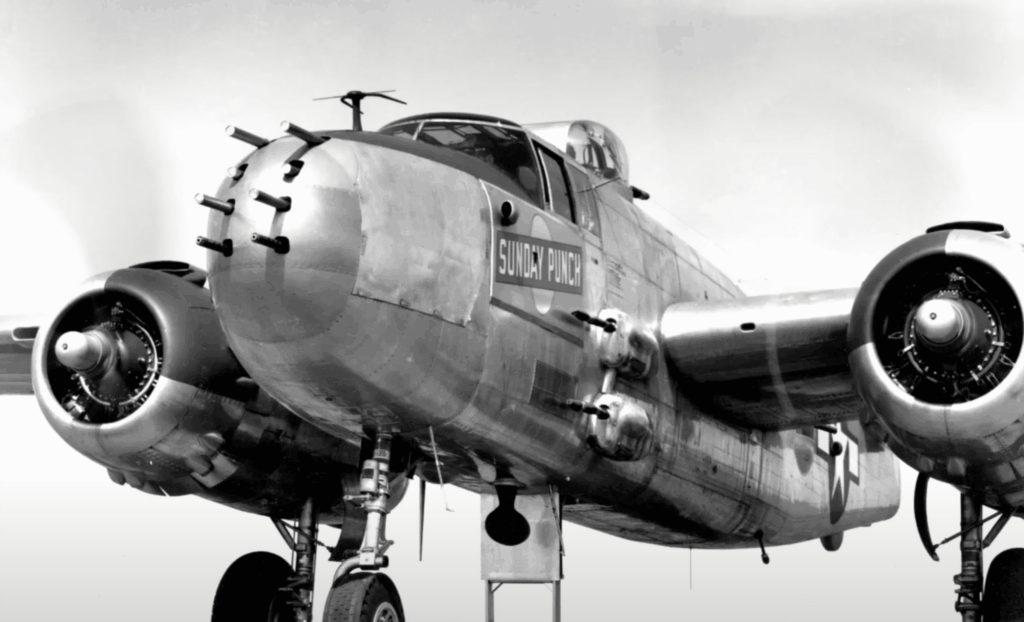

The B-25’s power was not limited to ships. It also struck Japanese airfields with devastating effect. In August 1943, strafing runs wiped out over 170 aircraft in a single series of low-level attacks. Pilots later described the terrifying sight of the bombers arriving almost at ground level, their eight nose-mounted machine guns firing streams of bullets that shredded everything in their path.

Shattering Warships and Reinforcements

The B-25’s effectiveness extended to major naval targets. At Biak in 1944, a destroyer group attempted to reinforce the island’s defenders. Just ten B-25s intercepted them. Concentrated fire from their eight-gun noses riddled the destroyer Harusame, and skip bombs soon sent it to the ocean floor. The reinforcement mission collapsed, leaving the defenders stranded and hopeless.

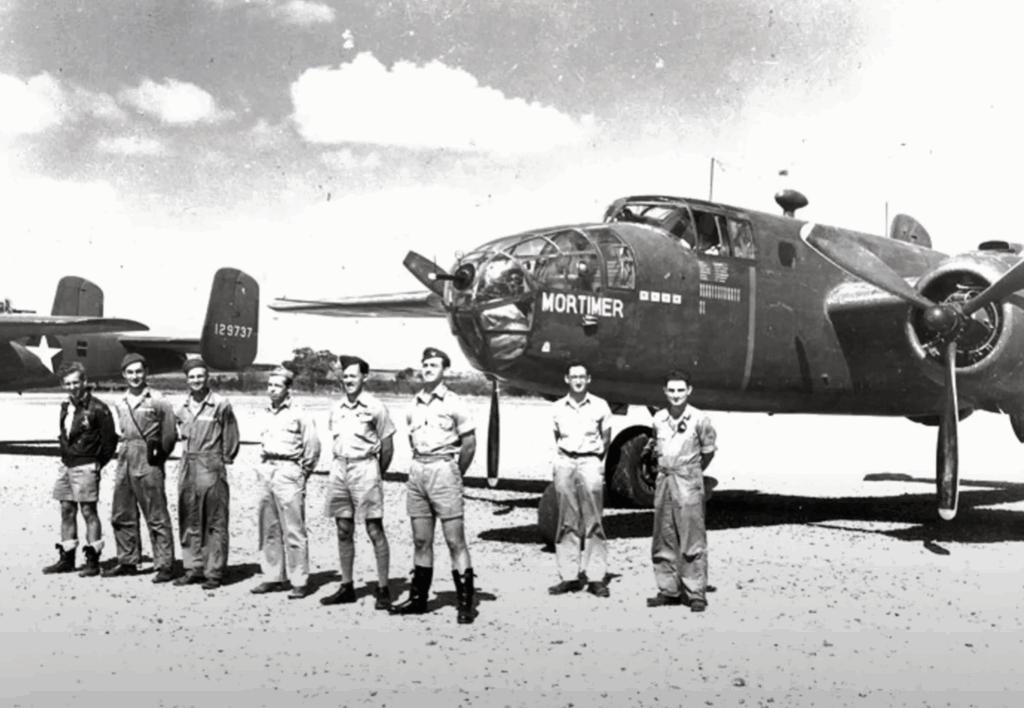

These missions shaped the identity of the crews. The men knew they were flying bombers unlike any others. Their aircraft carried names such as Dirty Dora and Hell’s Angel, often decorated with nose art and crew symbols. Pride came not just from victories but also from the psychological impact. Survivors of strafing runs recalled the memory of eight heavy machine guns roaring at once. Japanese officers wrote of nightmares involving the bombers, describing them as having “eight eyes of death.”

Innovation in the Pacific

Reports to Tokyo grew increasingly grim. One admiral conceded that the B-25 strafers were more destructive than submarines, more accurate than dive bombers, and more versatile than torpedo planes. In the Pacific, the Americans were not alone. Australian squadrons flying the same aircraft used their knowledge of local waters to ambush shipping in narrow channels and coastal coves, adding to the pressure on Japanese supply lines.

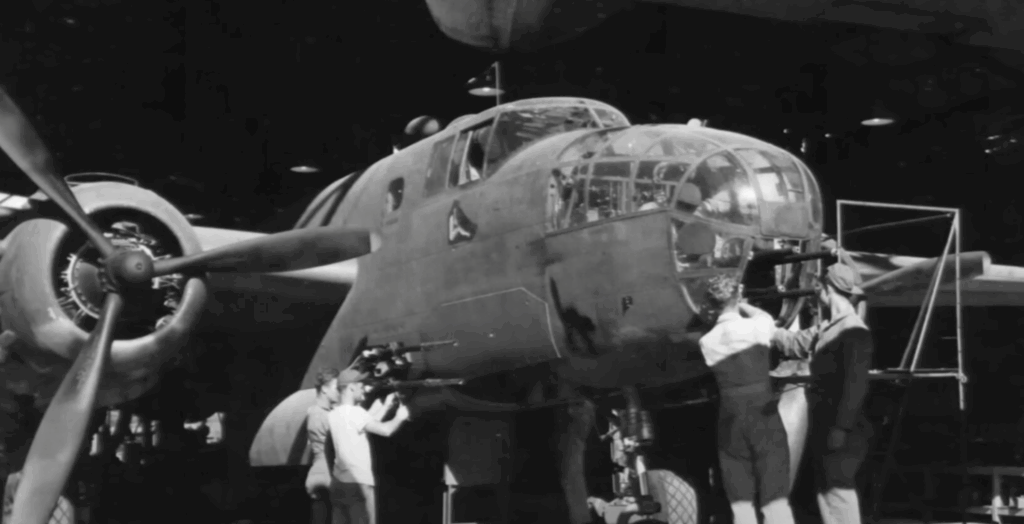

The aircraft itself continued to evolve. Later versions carried even heavier firepower, some mounting up to eighteen .50 caliber guns. Mechanics in field workshops modified standard bombers in just days, installing forward-firing guns and refining skip bombing techniques to hit ships exactly at the waterline. Much of this innovation came not from designers in factories, but from crews and engineers improvising in remote bases. Paul “Pappy” Gunn, a former airline mechanic turned combat engineer, became a driving force behind these modifications, turning the bomber into a true gunship.

The Toll on Crews

Japanese survivors later described the B-25 as a flying machine gun nest. Once its nose was pointed at a target, escape seemed impossible. Yet for American crews, each mission carried terrible risks. Strafing runs required flying low and directly into enemy fire, leaving little room for error. Many bombers never returned. The Third Attack Group alone lost more than forty aircraft during the war. Pilots endured tense seconds as they charged toward enemy ships, tracer rounds streaking toward them, and pulled up at the last instant to avoid crashing.

Despite the cost, the results changed the course of the Pacific War. B-25 strafers broke Japan’s supply chain, destroyed convoys, and crippled air power on the ground. They continued flying until the very last day of the war. On August 14, 1945, hours before the surrender announcement, B-25s struck Japanese ships in the Inland Sea. It was their final combat mission, ending the war the same way they had fought it—nose guns blazing, delivering destruction that no convoy could withstand.