See Series of Photos from the Battle of the Coral Sea, WWII’s First Aircraft Carrier Battle

Deadliest Disasters / YouTube

Rising Tensions in the Pacific

In the months following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Pacific became a place of constant danger. Japan’s forces quickly spread across East Asia, seizing the Philippines, Singapore, and other territories. By the spring of 1942, their next goal was to threaten Australia. If Port Moresby in New Guinea were captured, Australia’s sea routes to the United States would be endangered.

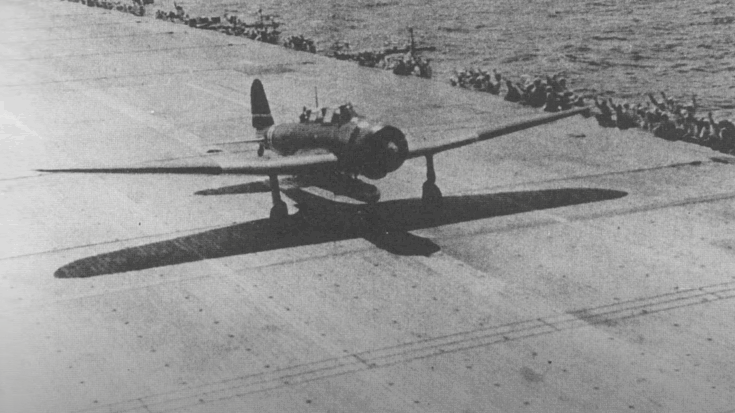

To stop this advance, the United States and Australia combined their strength. Two carrier task forces and an Australian cruiser squadron were sent north. By early May, these fleets gathered in the Coral Sea, off the coast of northeast Australia. What followed was unlike anything seen before. Ships did not fire directly on one another. Instead, planes launched from aircraft carriers became the deciding force. It was the first major battle where surface fleets never sighted each other.

Strategic Stakes and Early Moves

American leaders, including Admiral Chester Nimitz, understood the risk. Japan had launched Operation MO, planning to seize Tulagi and Port Moresby to isolate Australia. Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher commanded the American carriers Lexington and Yorktown, while Australian Rear Admiral John Crace led the cruiser group guarding the sea lanes.

On May 3, Japanese troops occupied Tulagi. The following day, carrier planes from Yorktown struck the harbor, sinking several ships. This marked the opening stage of the battle, though neither fleet had yet found the other’s carriers. Both sides sent out reconnaissance planes, knowing control of the sea would depend on locating the enemy first.

Losses at Sea and Acts of Bravery

On May 7, Japanese aircraft discovered the American oiler USS Neosho and destroyer USS Sims. Mistaking them for a carrier group, they launched a massive attack. Sims was struck repeatedly and exploded, taking nearly all of her crew down with her. Neosho was heavily damaged, and Captain John Phillips eventually ordered the ship abandoned.

Among the survivors was Corpsman Henry Tucker, who refused to leave the wounded. He swam from raft to raft with medical supplies, tending to burns and shrapnel injuries until he disappeared, never to be seen again. His actions became one of many small human stories that revealed the suffering and courage of sailors caught in the struggle.

Carrier Strikes and Heavy Casualties

That same day, American planes located and struck the Japanese light carrier Shōhō. Bombs and torpedoes tore into her, sinking the ship within minutes. Out of more than 700 crew members, only a fraction survived. This was a welcome success for Allied forces, proving that Japan’s carriers could be destroyed.

But the following day, May 8, the main carrier forces finally found each other. From more than 300 kilometers apart, both sides launched waves of aircraft. Yorktown was hit by bombs, while Lexington suffered devastating damage from torpedoes and secondary explosions. Fires raged uncontrollably, forcing the crew to abandon ship. By evening, the once-proud carrier had to be scuttled by American destroyers to prevent her from falling into enemy hands.

The Battle’s Outcome

Though the United States lost Lexington, the Japanese carriers also suffered. Shōkaku was badly damaged by bomb strikes and forced to retreat. Zuikaku, though intact, lost many of her aircraft and skilled pilots. Both were too weakened to take part in the next major clash at Midway a month later.

Casualties were severe on all sides, with thousands of sailors and airmen killed, wounded, or missing. Yet the Japanese invasion of Port Moresby was halted. Australia’s supply lines remained open, and the advance southward was checked. For the first time since Pearl Harbor, Japan’s expansion had been stopped.

See all the photos in the video below: