How Beatrice Shilling’s Ingenious Fix Saved 93 Planes in a Single Week

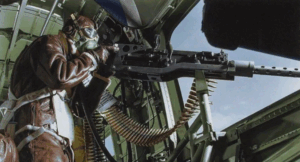

Royal Air Force, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Problem at 27,000 Feet

On April 8, 1943, high above the French town of Caen, the engines of a British Hawker Hurricane squadron roared as they chased a formation of German bombers. The air was thin, and the sky streaked with contrails and gunfire flashes. Lieutenant James Barlow, locked in pursuit, dived sharply—then silence. His Rolls-Royce Merlin engine suddenly died. It wasn’t a bullet or electrical failure. It was the same flaw that had haunted countless Royal Air Force pilots: fuel starvation in a dive.

As the ground rushed up, Barlow fought to restart the engine. At the last second, the Merlin coughed back to life, and he pulled the plane up, narrowly escaping death. His problem was not unique. The German fighters used direct fuel injection, which worked flawlessly at steep angles. British aircraft, by contrast, relied on carburetors that couldn’t handle negative G-forces. When the plane’s nose dropped, fuel flooded the carburetor, then cut off completely. The result was deadly silence in the middle of battle.

The Woman Behind the Solution

While officers debated and engineers searched for large-scale fixes, the answer would come from a quiet figure in an engineer’s uniform at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough. Her name was Beatrice Shilling. She wasn’t a general or a pilot, but a mechanical genius with a deep understanding of how engines breathed.

Shilling studied test data and knew that rebuilding the Merlin engine was impossible during wartime. Instead, she believed the solution lay in a small adjustment—a way to control fuel flow under pressure. Her idea was astonishingly simple: a small brass disc, no bigger than a coin, with a precisely drilled hole that could regulate the flow of fuel during negative G-forces. That tiny restriction would prevent both flooding and starvation.

The Test That Changed the War

In February 1943, Shilling tested her invention inside the roaring workshop at Farnborough. The air was heavy with oil and smoke as the Merlin engine spun on its test stand. She fitted the brass disc into the fuel line, tightened the bolts, and called for a simulated dive. The gauges dropped, the pressure shifted—and the engine kept running. For the first time, a Merlin didn’t stall in a dive. The workshop fell silent, then erupted in applause.

Her idea spread quickly. The RAF approved the fix and named it “Miss Shilling’s Orifice.” It could be installed in minutes, even at forward bases. Within one week, Shilling personally fitted the device to 93 aircraft across southern England. Pilots greeted her at each airfield, calling her a lifesaver. One told her, “You’ve saved our lives, Miss Shilling.” She simply replied, “No, you’re the ones saving ours.”

Turning the Tide in the Skies

Weeks later, the results were undeniable. RAF pilots who once feared diving in combat now attacked confidently. On May 15, 1943, over the French coast, Spitfire squadrons fought German fighters without a single engine stall. Lieutenant Ralph Dickinson wrote in his report, “I dove from 10,000 feet at 600 kilometers an hour, and the engine purred like a lion. It’s as if the aircraft was reborn.”

That day, the RAF destroyed fourteen enemy planes while losing only two of their own. Command recognized that Beatrice’s small device had changed the balance of air combat. Mechanics began pinning her photo on workshop walls with the caption: “The lady who made diving safe.” Her design soon spread to American units flying P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts. Across the Allied front, hundreds of aircraft carried her invention, saving countless lives.

Legacy of a Brilliant Engineer

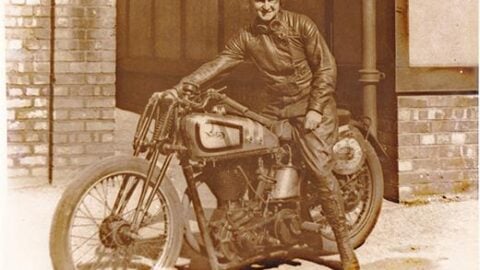

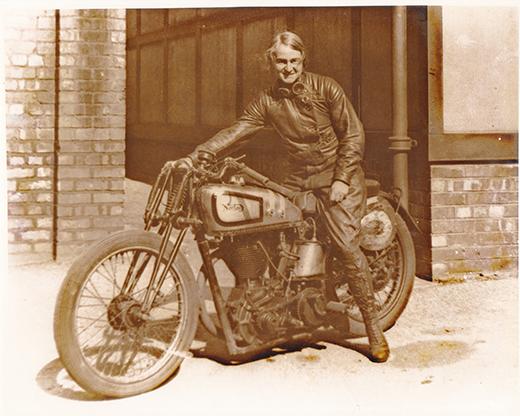

By late 1943, Beatrice was awarded the Order of the British Empire for her contribution. Yet she avoided the spotlight, saying simply, “I don’t fight in the sky—I just keep them flying.” After the war, she returned to the Royal Aircraft Establishment to study jet propulsion, but her love for speed never faded. On weekends, she raced her Norton 500cc motorcycle, often beating men twice her size.

In 1969, a veteran visited her office and said quietly, “Without you, I’d never have seen my children again.” She replied, “Without your courage, none of us would have a future.” When Beatrice Shilling passed away in 1990, newspapers remembered her with a simple line: “One woman kept Britain’s planes in the sky.” Today, her brass disc sits in the Imperial War Museum, a reminder that sometimes history turns not on weapons or ranks—but on the genius of a single engineer who refused to give up.