When Allied Pilots Tested a Captured Japanese Ki-84 — And Realized It Could Outclimb Their Best Fighters

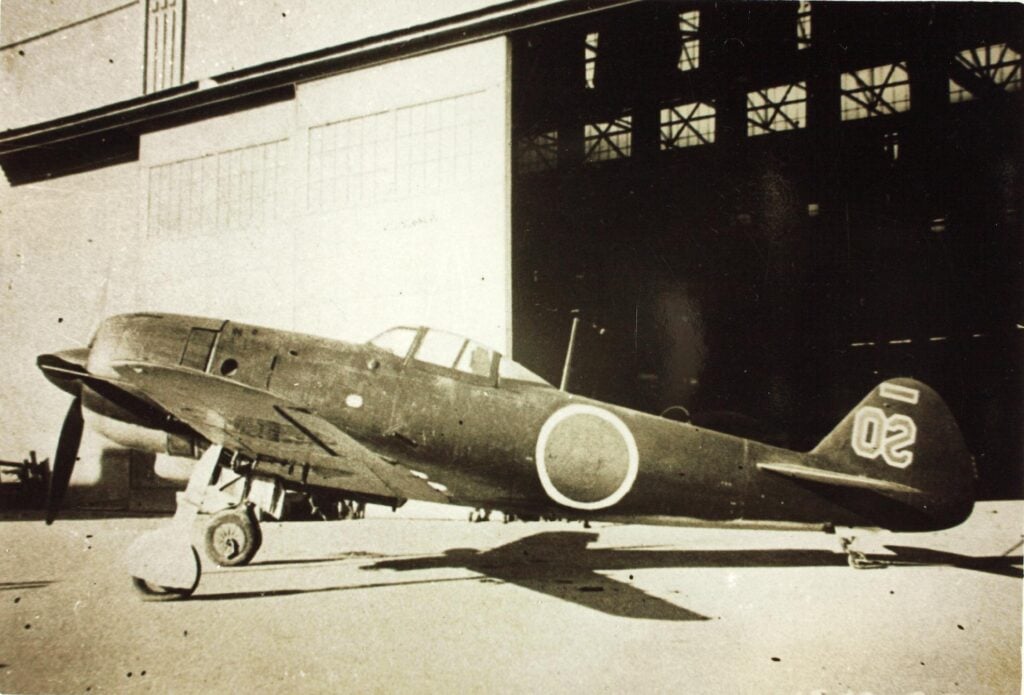

Photo by See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Fighter Beyond Expectations

In the summer of 1945, on a remote airfield in the Philippines, American pilots faced a puzzle. Reports had been coming in about a Japanese fighter unlike any they had encountered. Fast, maneuverable, and lethal, it had earned the nickname Frank. Experienced aviators were being outperformed, sometimes with deadly results. The aircraft’s official designation was Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate, but few in the U.S. military understood its true capabilities. When one was captured intact after Japanese forces abandoned an airfield, engineers and pilots finally had a chance to see it up close.

Major Thomas Blake, a veteran of combat over New Guinea, the Philippines, and Okinawa, knew Japanese planes well. He had flown against Zeros, Oscars, and Tonys, exploiting their weaknesses and avoiding their strengths. But the Ki-84 was different. Just weeks earlier, his squadron had engaged a formation over Luzon and lost two wingmen. The enemy aircraft had vanished into the clouds without losing a single plane. The captured fighter now rested on the tarmac, smaller than Blake expected, with patched metal and faded paint, yet it exuded a sense of precision and aggression that made even seasoned pilots uneasy.

First Flights and Shocking Performance

Captain Robert Chen, an experienced test pilot, approached the aircraft cautiously, running his hands along the fuselage and checking the controls. The radial engine had eighteen cylinders and, on paper, produced around 2,000 horsepower. Paper numbers, however, often misled. Only a flight could reveal the truth. Climbing into the cramped cockpit, Chen found the instruments marked in Japanese, but the layout was familiar. The moment he fired up the engine, its deep, aggressive roar made an impression. The aircraft leapt off the runway in less than 300 feet, climbing at a steep angle that defied expectation.

Once airborne, the Ki-84 revealed its qualities. The controls were exceptionally responsive; even the slightest input led to rapid changes in direction. The throttle reacted instantly, the rudder was sensitive, and the airframe remained stable at speeds above 350 mph. Chen tested its limits with steep dives, high-G turns, and rapid climbs. Every maneuver confirmed that the Ki-84 was built for combat, a machine designed to fight, not merely fly. When Blake took off in a P-51 Mustang for a mock engagement, the difference was striking. The Mustang, among the fastest fighters in the Allied arsenal, could not keep up. The Ki-84 pulled away in a vertical climb, outclimbing and outmaneuvering Blake with ease.

Understanding Its Implications

Back on the ground, pilots and engineers studied performance data. The Ki-84 had entered service in 1944, designed specifically to counter American fighters. It offered a faster climb rate, tighter turn radius, and superior acceleration. The Mustang’s only advantage was range, which mattered little in a dogfight. Observers realized that American assumptions about Japanese aircraft were incomplete. The fighter was exceptional, but the enemy could not deploy it in large numbers. Bombing campaigns had destroyed infrastructure, fuel was scarce, and experienced pilots were in short supply.

Despite its limitations in the field, the Ki-84 demonstrated the danger of underestimating the enemy. When tested against large formations of Allied bombers and P-51 escorts, even a small number of Ki-84s could inflict serious damage. Each flight against it required precision, timing, and strategy. Pilots quickly learned that in combat, small advantages could determine survival. Over several days, Blake and others flew repeated exercises against the captured fighter, consistently discovering that any pilot facing the Ki-84 in the air would be challenged, sometimes fatally, if the opponent knew how to use it.

Legacy of the Ki-84

The captured Ki-84 was eventually shipped to the United States for detailed study. Pilots were briefed, engineers dissected its design, and new tactics were developed based on what it had revealed. The aircraft itself, silent and still in the hangar, left a lasting impression. For Blake and Chen, it was a reminder that in war, raw skill, industrial capacity, and logistics often mattered as much as the capabilities of a single machine. The Ki-84 had shown what could be achieved with careful design and understanding of aerial combat, but in the end, production limits and strategic conditions had prevented it from changing the course of the conflict.