How a Chinese American Ace Pilot Became Japan’s Worst Nightmare Before the Flying Tigers

http://tushu.junshishu.com/Digest_648_1.html, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The War Before the World War

In July 1937, a clash near the Marco Polo Bridge ignited full-scale war between China and Japan. Though not officially part of World War II, this brutal conflict overlapped with it and lasted until Japan’s surrender in 1945. At the time, the Chinese Air Force relied heavily on imported aircraft, mostly American-built fighters such as the Curtiss Hawk III and Boeing 281, an export version of the P-26 Peashooter. There were also a few European designs, like the Italian Fiat CR.32.

China’s leaders had ambitious plans to strike back, even imagining bombing raids on Tokyo. But these early hopes vanished after devastating losses in the first month of fighting. Desperate for help, China turned to the Soviet Union, which provided Polikarpov I-15 and I-16 fighters and Tupolev SB bombers—fast, reliable, and better suited for modern combat. The British also contributed by selling 36 Gloster Gladiators, agile biplane fighters that would soon see fierce action in the skies over China.

The Rise of Arthur Chin

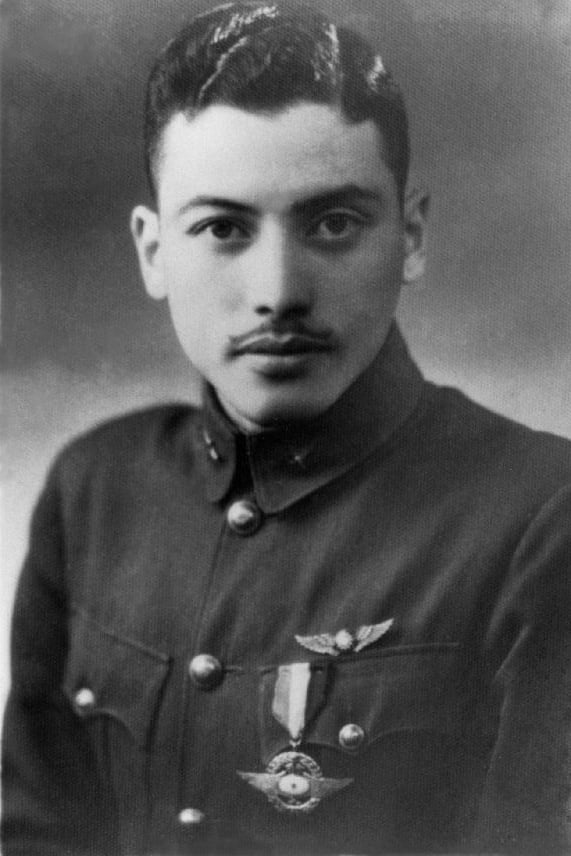

Among the new generation of pilots was Arthur Chin, or Chan Sui-Tin, a Chinese American of mixed Chinese and Peruvian heritage. He was one of fifteen Chinese Americans who volunteered to fight for China in the early 1930s, long before the United States entered the war. Motivated by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, Chin joined the Cantonese Air Force, later transferring to the Central Chinese Air Force after training in Germany in 1936.

By June 1937, he had become vice commander of the 28th Pursuit Squadron. Flying the outdated Curtiss Hawk II, Chin scored two victories that summer. In February 1938, his unit received the new Gloster Gladiator fighters, offering a much-needed boost in performance. However, his first flight with the aircraft ended badly when a snowstorm forced him into a crash landing, leaving him injured and grounded for weeks.

A Fighter Reborn

Despite his rough start, Chin’s combat record would soon soar. On May 31, 1938, his squadron intercepted nine Japanese Navy floatplanes near Hukou. Using the Gladiator’s superior speed and climb rate, Chin dove from above and shot one down after a 30-minute battle. The wreckage confirmed his victory. This success earned him promotion to captain and command of the 28th Squadron.

Just two weeks later, on June 16, Chin joined a formation of Gladiators led by fellow Chinese American John Wong. They encountered six Japanese bombers flying in two tight groups. Wong destroyed the lead bomber by igniting its external bomb load, while Chin set another ablaze. The engagement lasted over an hour, and though Chinese records claimed several kills, it was clear that Chin’s leadership and skill had made a difference.

Against Overwhelming Odds

In August 1938, Chin led seven Gladiators against a large formation of Japanese A5M “Claude” fighters. Outnumbered at least four to one, his squadron fought fiercely. Chin saved his vice commander from enemy fire and later protected a wingman who was being chased by several Claudes. During the fight, his Gladiator was riddled with bullets. The armor plate behind his seat saved his life. When his plane was too damaged to continue, he rammed an enemy fighter before bailing out.

After being hospitalized, he was visited by Claire Chennault—the future leader of the Flying Tigers—who praised his courage. Chin humorously asked if he could trade the machine gun salvaged from his wreck for a new plane so he could return to the fight.

The Last Battles

By late 1938, Chin’s unit began transitioning to Soviet I-15 fighters, but he remained loyal to the Gladiator. In 1939, now a major, he led guerrilla-style air operations against Japanese forces in southern China. On December 27, 1939, he flew his final combat mission, escorting bombers alongside Soviet crews. During the battle, Chin downed two enemy fighters before his own Gladiator was set ablaze. Severely burned, he bailed out over friendly territory and survived.

After months of recovery, Chin escaped from Hong Kong when Japanese attacks began and returned to the United States with his family. Though his combat days were over, he later flew transport missions for the U.S. Army Air Forces over the Himalayas in 1945.

Legacy of a Forgotten Hero

Arthur Chin ended his career with eight confirmed aerial victories, making him the top Chinese biplane ace of the war. He died in 1997 in Portland, Oregon, remembered as the Chinese American pilot who fought for freedom years before the Flying Tigers ever took to the sky.