How One Colonel’s Ridiculous Idea Crushed the Luftwaffe’s Perfect Defense

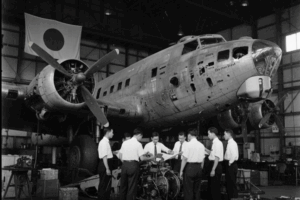

Historic Warframes / YouTube

The Suicide Mission

In early 1944, attacking a German airfield was one of the deadliest assignments an American fighter pilot could face. Casualty rates for these missions were four times higher than dogfights in the sky. Men who had survived months of combat against the best enemy aces were being lost to ground gunners they never even saw.

The reason was the Germans’ defensive setup, known among pilots as the Feuerwand — or “firewall.” Every airfield in occupied France had become a fortress of anti-aircraft guns. Between forty and eighty flak guns surrounded each base, layered to trap anything that approached. The Germans were not just well-armed — they were clever. They studied the weather and realized most planes took off and landed heading east, into the prevailing wind. American pilots, trained the same way, always attacked from the east to get the most stable firing run. That predictability was fatal.

The Perfect Trap

The Germans concentrated their heaviest guns — the 37mm and 40mm cannons — on the eastern sides of their runways. These weapons created a dense, pre-aimed kill zone. When American fighters came in low and fast from the east, they were met with an invisible curtain of shrapnel. Dozens of planes were torn apart before they could even fire. The Eighth Fighter Command was losing men at a rate that could not be sustained.

That changed when Colonel Hubert “Hub” Zemke, commander of the famed 56th Fighter Group, decided to study the problem himself. Zemke was not only a pilot — he had an engineer’s mind. He gathered reconnaissance photos, interviewed surviving pilots, and plotted flak positions on maps. When he looked at the data, something obvious appeared. The airfields were heavily fortified on the eastern approach but almost bare on the western side. No one attacked from the west because it went against everything pilots were trained to do. Zemke began to wonder if that rule itself was the problem.

The Wrong Way

His idea sounded ridiculous. What if, instead of attacking with the wind, they attacked against it — from the west? His staff objected immediately. A westward attack meant flying crosswind, less time on target, and more danger during takeoff and escape. Zemke listened, then gave a simple answer: “Dead pilots can’t destroy anything. A live one can make another pass.”

On May 8, 1944, Zemke’s theory was tested at the Aschersleben airfield — one of the most heavily defended bases in France. Sixteen P-47 Thunderbolts, flown by top aces like Walker Mahurin and Robert Johnson, prepared for the attack. Instead of the usual eastern approach, they came in from the west, flying so low their propellers nearly touched the trees.

Breaking the Firewall

The result was chaos. The German radar barely registered the incoming fighters before they were already over the field. The flak crews scrambled to respond, but their guns were pointed in the wrong direction — all facing east. It took several seconds for the heavy cannons to turn, and by then it was too late. The P-47s swept across the airfield, their eight .50-caliber machine guns tearing through rows of parked aircraft. Fuel trucks exploded, hangars caught fire, and the defenders could do nothing but watch as the attackers vanished beyond the horizon.

In less than a minute, the 56th Fighter Group had destroyed twenty-three enemy planes. Not one American aircraft was lost. The “suicide mission” had just turned into a near-perfect strike. For the first time, the infamous “firewall” defense had completely failed.

Turning the War on the Ground

Word of Zemke’s attack spread quickly. Within days, his “wrong way” strategy was adopted across the Allied air forces. In the two weeks before D-Day, nearly three-quarters of all strafing missions used the new reverse approach. The results were dramatic: the loss rate dropped from over eight percent to just two, while the number of enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground doubled.

The Germans tried to adapt, shifting guns and reinforcing western flanks, but it was too late. Their airfields had been built to face east — redesigning them in the middle of a war was impossible. Zemke’s simple change had revealed a critical weakness in their entire system.

By June 6, 1944, when Allied troops landed in Normandy, the Luftwaffe’s once-proud air fleet was already crippled — not just in the skies, but at its own bases. The “perfect defense” that once made airfield attacks suicidal had been undone by one man who dared to think the wrong way.