The Tragic Tale of Dennis Copping’s P-40

YouTube / Rex's Hangar

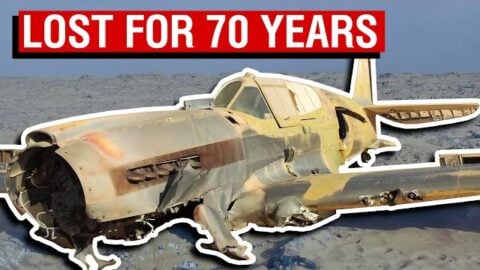

In May 2012, a Polish oil company worker stumbled upon the wreck of a Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk fighter, an American-built aircraft supplied to Britain through the Lend-Lease program. It had once served with the Royal Air Force during the North African campaign of World War II. Records suggested it was lost on June 28, 1942, when its pilot, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping, was forced to land while ferrying the plane for landing gear repairs.

What Went Wrong

The dry desert air kept the P-40 in surprisingly good condition, even after almost seventy years. Its discovery brought back memories of the fierce battles fought across North Africa in 1942, when Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Panzer Army Afrika pushed the British Eighth Army toward Egypt.

By late summer, the British, now under General Bernard L. Montgomery, were preparing a major counterattack. The famous Battle of El Alamein, a pivotal battle, began in October 1942 and ended in a decisive Allied victory, marking a key turning point in World War II. Flight Sergeant Copping’s ordeal may have come from efforts to get every available British aircraft ready for this crucial offensive.

Military historian Andy Saunders explained in an interview with CNN that 24-year-old Copping likely got lost while ferrying his P-40 for landing gear repairs. Another pilot from 260 Squadron tried to signal him that he was flying the wrong way, but Copping didn’t respond. Eventually, his plane ran out of fuel, forcing him to make an emergency landing in the desert.

The P-40 was damaged when it hit the ground. Its propeller and nose were torn off, and the landing gear collapsed. Still, the rest of the plane stayed in good shape. Even decades later, the cockpit instruments were intact, and much of the interior looked almost untouched, as if time itself had stood still.

Vanished in the Sahara

It appears that Flight Sergeant Copping survived the crash- at least for a short time. Evidence at the site suggests this, including a parachute that had been stretched out to provide shade. It seems he stayed near the plane at first, trying to shield himself from the relentless Saharan sun.

“The parachute gives him shelter and a means to be identified from the air,” explained historian Andy Saunders. “He also would have had a small silver signaling mirror to catch the attention of passing aircraft, and a pistol with a few flares. But his chances of survival were not good.”

RAF pilots didn’t carry much in the way of food or water, and the P-40’s radio was probably damaged in the crash. Alone, stranded, and running out of options, Copping may have decided his only hope was to set out on foot, heading toward where he believed help might be.

No human remains have ever been found, and even today, the odds of discovering what became of Flight Sergeant Copping remain extremely slim.