Why Curtiss Final WWII Fighters the XP 62 and XF14C Ended in Failure

IHYLS / YouTube

A Company Searching for Relevance

By the early 1940s, Curtiss-Wright was a well-known aircraft maker but no longer a leader in combat designs. Its P-40 Warhawk had served widely, and the SB2C Helldiver filled an important dive-bomber role, yet neither matched the performance of newer American fighters. Curtiss supplied engines, parts, and trainers, but the firm wanted to return to the front line with advanced combat planes. Determined to prove it could still compete, the company set out to build powerful new fighters for both the U.S. Army Air Forces and the Navy. The effort produced two ambitious projects—the XP 62 and the XF14C—that would become symbols of high hopes and repeated setbacks.

Army Requirements and the XP 62

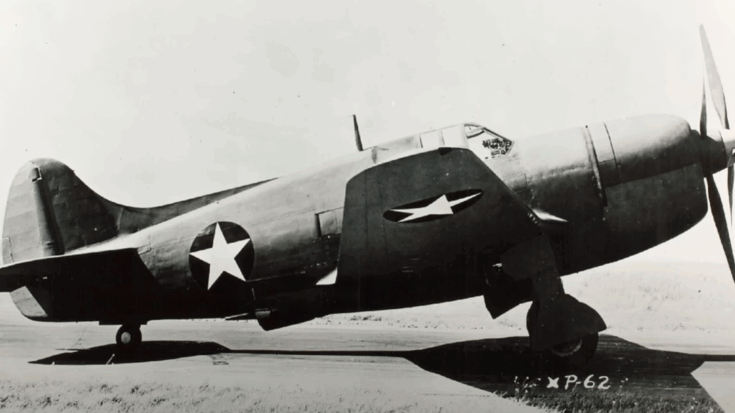

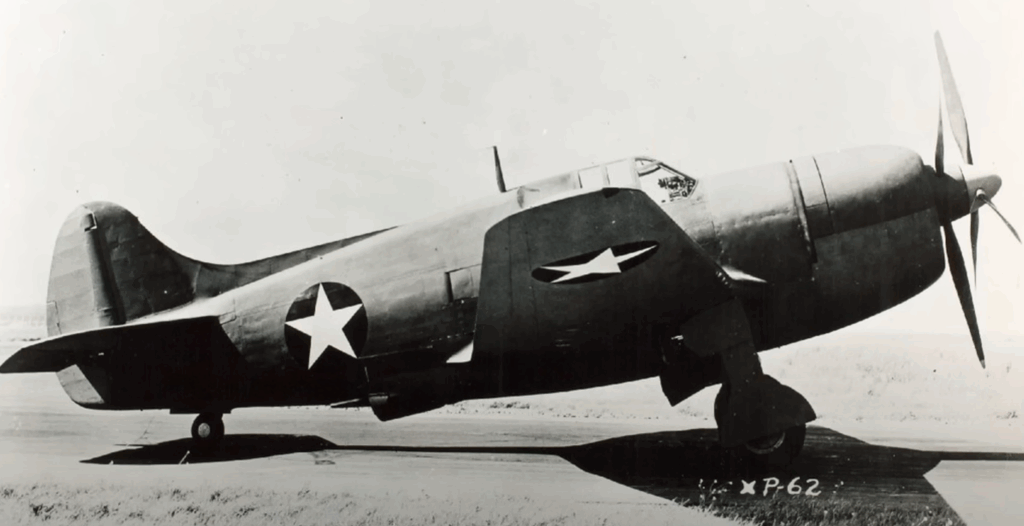

In January 1941 the Army sought a high-altitude interceptor with great speed and heavy firepower. Curtiss proposed a single-engine fighter built around its own Wright R-3350 Cyclone engine, one of the most powerful radials available. Early goals called for a top speed near 468 miles per hour at 27,000 feet, a pressurized cockpit, and either twelve .50-caliber machine guns or eight 20 mm cannons. Meeting those demands required a large airframe: the XP 62 stretched over 40 feet in length with a wingspan more like a twin-engine aircraft. Designers even planned counter-rotating propellers to control the engine’s torque.

The project soon ran into trouble. The special engine and propeller combination was delayed, forcing Curtiss to install a standard single propeller. Weight estimates kept rising, and the heavy armament reduced expected speed to about 448 miles per hour. The Army ordered two prototypes in mid-1941 but soon focused on urgent production of P-47 Thunderbolts and B-29 bombers, which used the same R-3350 engine. Contracts for 100 production aircraft were cancelled in 1942 before the prototype even flew.

A Late First Flight

Curtiss pressed on with its two prototypes to test the pressurized cockpit, but progress was slow. The first XP 62 finally flew in July 1943, well after the original schedule. By then the Army had little interest, and only a few hours of flight testing were logged. The second prototype was abandoned, and the lone XP 62 was scrapped early the next year. Though impressive on paper, it never had a chance to prove its worth.

Navy Ambitions and the XF14C

The Navy also explored advanced fighters in 1941, experimenting with a liquid-cooled Lycoming XH-2470 engine that promised high power with less weight than a radial. Curtiss received a contract for two prototypes, designated XF14C. Early estimates suggested a top speed of about 374 miles per hour, but wind-tunnel tests raised doubts, and the Lycoming engine suffered delays. By late 1943 the Navy cancelled the first design before a prototype could fly.

Curtiss reworked the aircraft as the XF14C-2, replacing the troubled inline engine with the familiar R-3350 radial and adding a turbo-supercharger for altitude performance. The modified fighter flew in July 1944 and reached about 398 miles per hour—short of the hoped-for 424. Engine vibration and changing wartime needs further weakened the case for production. A final high-altitude version with a pressurized cockpit, the XF14C-3, was studied but dropped in 1945.

The End of Curtiss Fighters

The XP 62 and XF14C shared a pattern of over-ambitious goals, delays, and shifting priorities. Both relied on engines that were in heavy demand elsewhere, and both entered testing long after faster and more reliable fighters were already in service. After these disappointments, Curtiss chose to leave combat aircraft development and focus on components and systems—a business it continues in today.