How One “Rejected” U.S. Engineer Created the Plane the Luftwaffe Couldn’t Defeat

Logawi (original uploader), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the years before the Second World War, one young engineer faced skepticism from military officials yet went on to create one of the most effective combat aircraft in history. His work marked the shift from conventional designs to machines built for performance, range, and surprise. This is the story of Clarence “Kelly” Johnson and how his design helped change the air war during that conflict.

Early Struggles and Breakthroughs

Clarence Leon “Kelly” Johnson was born in 1910 in Ishpeming, Michigan, into a family of nine children with modest means. After college and a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, he joined Lockheed Corporation in 1933 as a tool designer. Early on he demonstrated an ability to see problems in aircraft stability that others overlooked. Despite some initial resistance from military advisors, he moved quickly into the role of aeronautical engineer.

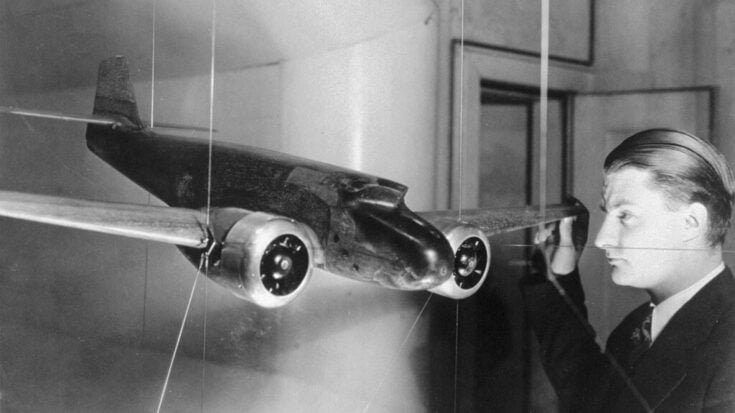

In 1937, the U.S. Army Air Corps issued a requirement for a high-altitude twin-engine fighter. Johnson and Lockheed responded with the XP-38 prototype. The design featured a central fuselage pod, twin booms and two powerful supercharged engines. At first many in the establishment considered it risky or unconventional. Yet the proto-type flew for the first time in January 1939.

The P-38 Lightning and Air War Impact

The production version of the aircraft, named the Lockheed P‑38 Lightning, began to enter service in 1941-42. It was the first American fighter to exceed 400 mph, and boasted a range that rivalled bombers of the time. Its long reach and twin-engine reliability allowed it to carry out missions that other single-engine fighters simply could not. In the Mediterranean theatre and later in the Pacific, the P-38 proved itself against German and Japanese opposition.

Johnson’s rejection by some corners of the military did not stop him from pushing the aircraft into operational use. His motto—“Be quick, be quiet, be on time”—became part of how he ran his design teams. Under his leadership, the P-38 also achieved a notable interception mission in the Pacific that struck at a major Japanese naval figure.

From Fighter to Innovation Machine

Johnson did not stop at the P-38. After the war started changing from propeller to jet power, he set up and led the famed Skunk Works at Lockheed. That small, highly focused team produced aircraft that set speed and altitude records: the U-2, the SR-71 “Blackbird,” and other design breakthroughs. His management style emphasized small teams, rapid decision-making and keeping bureaucracy out of the way.

His dedication to simplifying design, stressing performance and treating production as part of engineering distinguished him from many contemporaries. He believed a first sketch should be flight-worthy and saw production constraints as part of design problems, not external limits.

U.S. Air Force photo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Legacy of Innovation

Johnson remained at Lockheed until his formal retirement in 1975, but his influence extended long after. He designed or had major input into over forty military and civilian aircraft. His work on the P-38 and later projects reshaped American air-power, moving the focus from numbers and armor to reach, speed and strategic flexibility.

In recognition of his contributions he received many awards including the National Medal of Science and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. His story also shows how rejection by one institution can turn into opportunity when driven by vision, care, and hard work.

The P-38 Lightning remains a symbol of that transformation. And Johnson’s role in its creation illustrates how one individual’s belief in a better design can change the outcome of conflict.