The Bizarre Fat Airplane that Changed Military Aviation Forever

YouTube / Dark Skies

In the early 1930s, aviation was a playground for wild ideas. Streamlined monoplanes shared the skies with clumsy biplanes, and engineers across Europe were chasing the future of flight. But even among the strangest designs of the decade, one stood out — the Italian Stipa-Caproni, a plane so odd it looked like it belonged in a cartoon rather than a hangar.

The Flying Barrel

Italian engineer Luigi Stipa envisioned a new kind of aircraft that could make propellers more efficient. Drawing on the Bernoulli Principle, he theorized that enclosing a propeller inside a tube could accelerate airflow and boost thrust. His idea became known as the “intubated propeller,” and in 1932, the Italian Air Ministry gave him permission to test it.

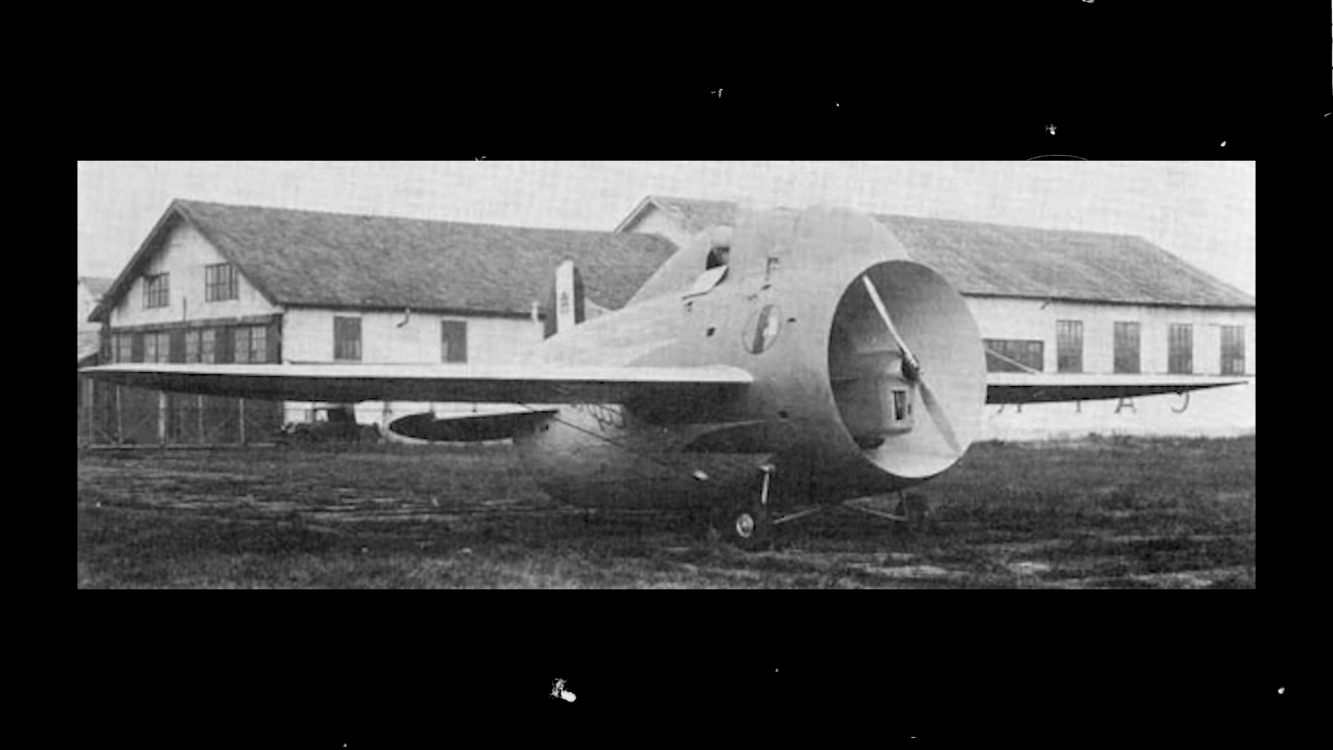

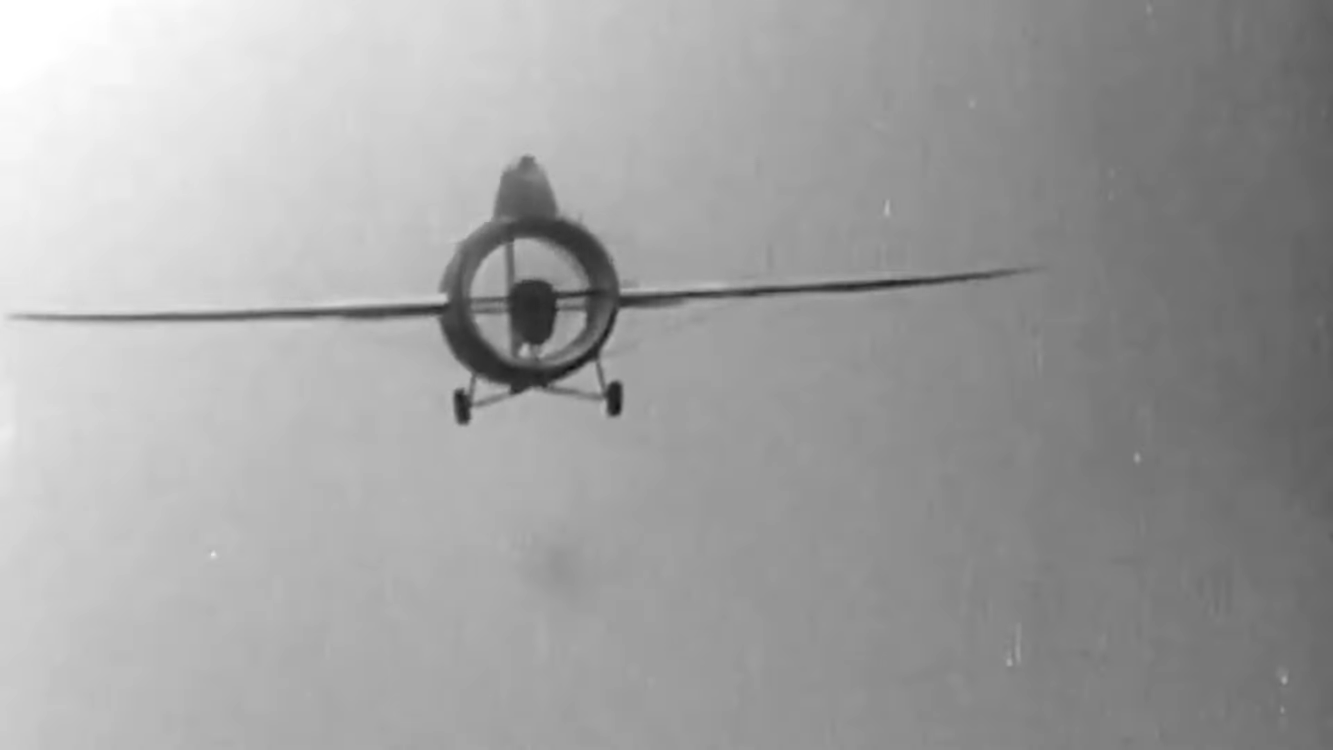

Working with the Caproni company — famous for building Italy’s largest wartime bombers — Stipa created a small, stubby prototype. Its fuselage was a hollow cylinder with a propeller spinning deep inside, powered by a 120-horsepower de Havilland engine. With short wings and a hump-backed cockpit, the aircraft looked more like a flying barrel than a serious experiment.

A Strange Success

When test pilot Domenico Antonini took the Stipa-Caproni aloft, witnesses could hardly believe it could fly. Yet it did — and surprisingly well. The “flying barrel” proved stable, quiet, and capable of climbing faster than other aircraft using the same engine. However, it was almost too stable, making it sluggish to turn. The thick tubular fuselage also created enormous drag, which canceled out many of its aerodynamic benefits.

Even so, Stipa’s theory worked in principle. The design improved propeller efficiency, demonstrated smoother airflow, and hinted at something revolutionary. Though the Italian Air Force decided not to pursue it, the lessons learned from the Stipa-Caproni quietly shaped aviation’s future.

Ahead of Its Time

Stipa patented his concept in Italy, Germany, and the United States. His “intubated propeller” would later influence the development of ducted fans and even early jet propulsion research. Engineers from France and Germany studied his work, and by the late 1930s, similar principles appeared in experimental aircraft like the Heinkel “T” fighter and the Caproni-Campini N.1 — one of the first planes to fly with a ducted-fan jet engine.

While Stipa never received full credit, historians now see his work as a critical stepping stone toward the turbofan engines that power modern airliners and fighters alike.

The Legacy Lives On

Stipa died in 1992, still convinced his ideas had been borrowed by others. But his legacy endures. In Australia, engineers built a 3/5-scale replica of his “flying barrel,” painted in the same cream and blue as the 1932 original. It flew twice before becoming a museum exhibit at Toowoomba City Aerodrome — a tribute to the man who looked at a propeller and saw the future.

The Stipa-Caproni may have looked ridiculous, but it proved a powerful truth: sometimes, the strangest ideas can reshape the skies!