He Was Supposed to Snap Photos Instead He Wiped Out 40 Enemy Planes

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/6608416, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Discovery Over Paleolu

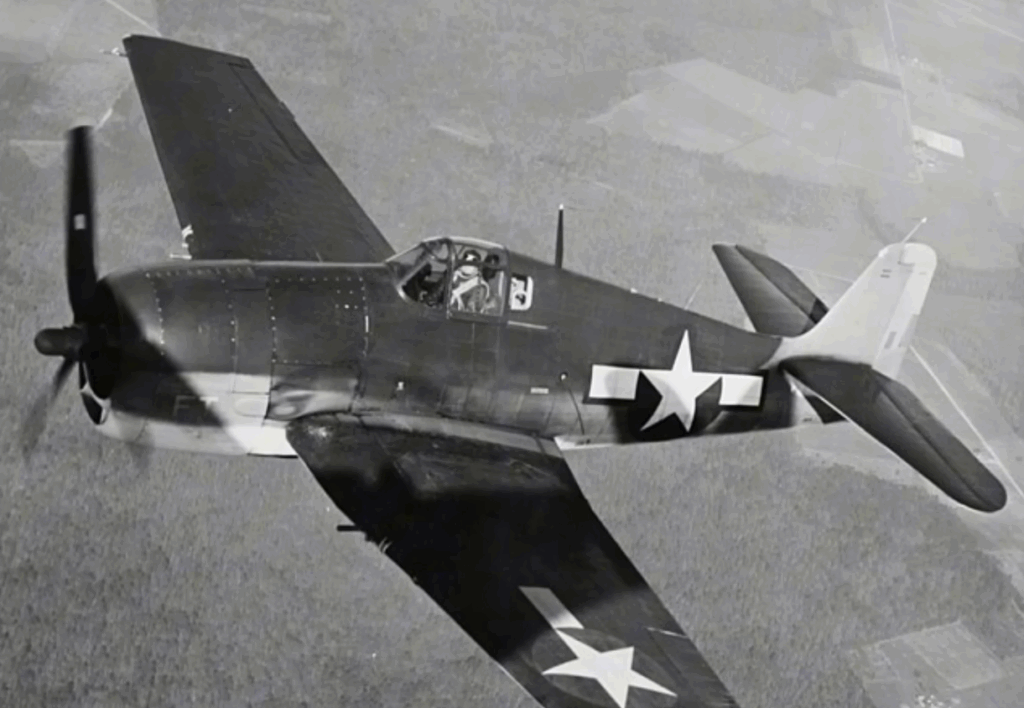

On September 12, 1944, Major Robert “Cowboy” Stout took off from the USS Hornet in his F6F Hellcat with a straightforward mission: photograph the northern airfield of Paleolu and return. Intelligence reports had assured him the field was abandoned, likely damaged by earlier attacks. But as Stout flew over at 8,000 feet, his eyes widened. The airfield was alive with Japanese aircraft—Mitsubishi Zeros, Nakajima bombers, all lined up wingtip to wingtip, fuel drums stacked, and ground crews bustling around. He quickly counted at least 40 planes, fully armed and fueled, poised to strike the Marines landing in three days. Stout’s mind raced. Following orders meant reporting and waiting for reinforcements, which could take hours or even a day. By then, these planes might scatter, hide, or attack the invasion fleet. Time was too short for proper procedure.

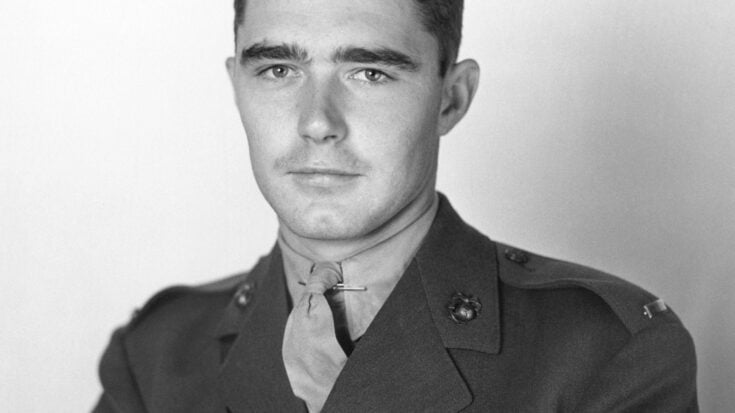

Stout studied the airfield carefully. The enemy had made a critical error: the planes were tightly packed near exposed fuel drums. One well-placed attack could trigger a chain reaction. He checked his ammunition—2,400 rounds of .50 caliber, roughly 12 seconds of sustained fire. Not enough to destroy each plane individually, but enough to ignite a massive inferno. Stout was no reckless pilot. At 28, he had survived 63 combat missions, dogfights, and landings in dangerous conditions. He knew the risk. Attacking meant facing every anti-aircraft gun on the island alone. One lucky hit could end him. Not attacking meant certain death for many Marines. His experience told him what mattered most: action now, not later.

The First Strike

He pushed the throttle forward and dove toward the jungle canopy. At 2,000 feet, the Hellcat roared near 400 mph as it leveled off above the airfield. Japanese crews scattered in panic. Stout opened fire on the northern row, aiming first at the fuel drums between bombers. Tracers tore through the air, igniting a massive fireball that engulfed two aircraft instantly. The flames spread quickly, consuming half the northern row within seconds. Anti-aircraft guns opened fire, but Stout had already begun climbing away, weaving to avoid tracers. The northern section burned fiercely, but 20 aircraft remained on the southern end. He had only six seconds of firing left, yet he chose to return.

This second run was even more dangerous. Anti-aircraft fire was immediate and intense. Stout approached from a new angle, firing at bombers and a fuel truck that exploded, flipping nearby aircraft and setting off ammunition crates. Secondary explosions tore through the southern row. Within moments, all 40 planes were burning. The Hellcat bore damage: control surfaces shredded, smoke trailing, but the engine held. Stout climbed, leaving behind an airfield reduced to flames and rubble.

Return and Recognition

The return flight to the Hornet was tense. Hydraulic failures made controls sluggish, and the landing gear partially failed. He managed to catch the second wire, slamming onto the deck with a damaged aircraft. Onlookers were stunned. Stout reported simply: the airfield wasn’t abandoned, and all 40 enemy aircraft were destroyed in eight minutes. Reconnaissance confirmed the destruction. The Marines would face the beaches with complete air superiority. Stout was awarded the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism, saving hundreds of lives by acting decisively when procedure demanded patience.

After the war, Stout lived quietly in California, rarely speaking of the mission. Historians later confirmed the attack’s full impact. One pilot, eight minutes, 40 planes destroyed, and potentially a thousand lives saved. His action is studied in military training as an example of initiative, target prioritization, and tactical judgment under extreme pressure. Stout’s choice shows that sometimes following orders strictly is less important than understanding the mission’s intent and adapting when circumstances demand.