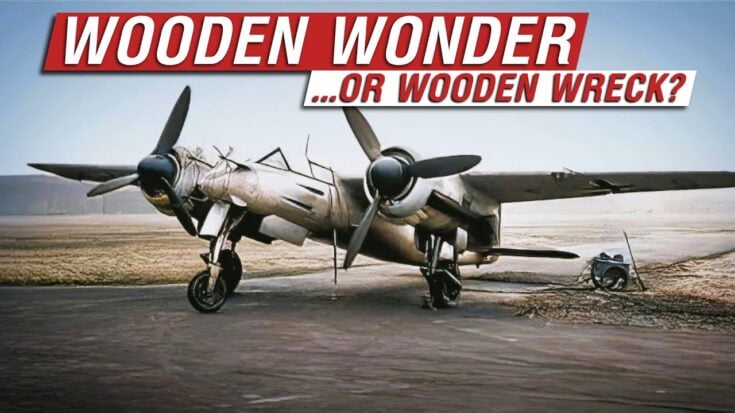

Why Germany’s Wooden Wonder Didn’t Work

YouTube / Rex's Hangar

When it comes to wooden aircraft of World War II, the British De Havilland Mosquito stands unmatched. Built largely from plywood and other non-strategic materials, it became one of the war’s most versatile and feared aircraft. The Mosquito quickly earned respect across the skies, and naturally, Germany wanted an answer.

That answer was the Focke-Wulf Ta 154—a wooden night fighter that began with high hopes but ended in frustration, failure, and broken airframes scattered across German airfields.

A Desperate Answer to the Mosquito

By 1942, the Luftwaffe was under pressure. Its heavy bombers were outdated, and its twin-engine Bf 110s and Ju 88s struggled against Allied raids. Field Marshal Erhard Milch pushed for a fast wooden aircraft, partly to save aluminum for other projects and partly to make use of Germany’s plentiful Junkers Jumo 211 engines.

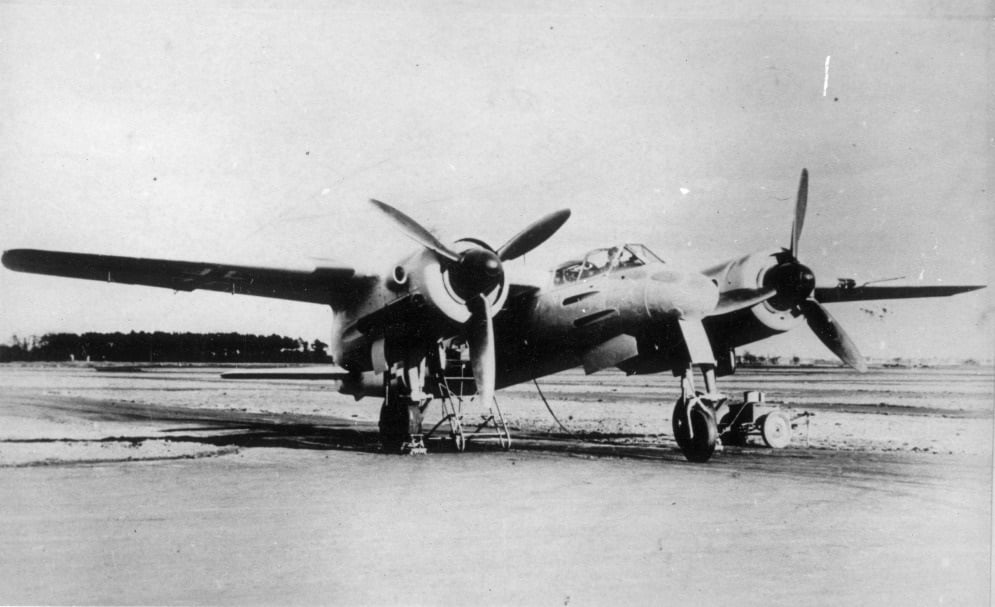

Focke-Wulf’s Kurt Tank led the effort. The plan was ambitious: a lightweight wooden airframe bonded with advanced adhesives, powered by twin Jumo engines, and armed with heavy cannon for night interceptions. On paper, it looked promising. In practice, it quickly became a nightmare.

Promising Start, Swift Decline

The first Ta 154 prototype flew in July 1943. In early trials—light, unarmed, and without bulky radar—the aircraft impressed. Reports claimed it could reach over 430 mph and outmaneuver rivals like the Heinkel He 219. But once weapons, radar, and flame dampeners were installed, its performance dropped sharply.

Landing gear failures plagued the prototypes, leading to repeated crashes. Even worse, structural vibration from the cannons sometimes shook parts of the fuselage loose. Fatal accidents followed, including a cockpit-crushing crash that killed both crewmen, forcing engineers to redesign the nose in metal.

What was supposed to be Germany’s “wooden wonder” was already becoming less wooden just to survive.

The Fatal Glue Problem

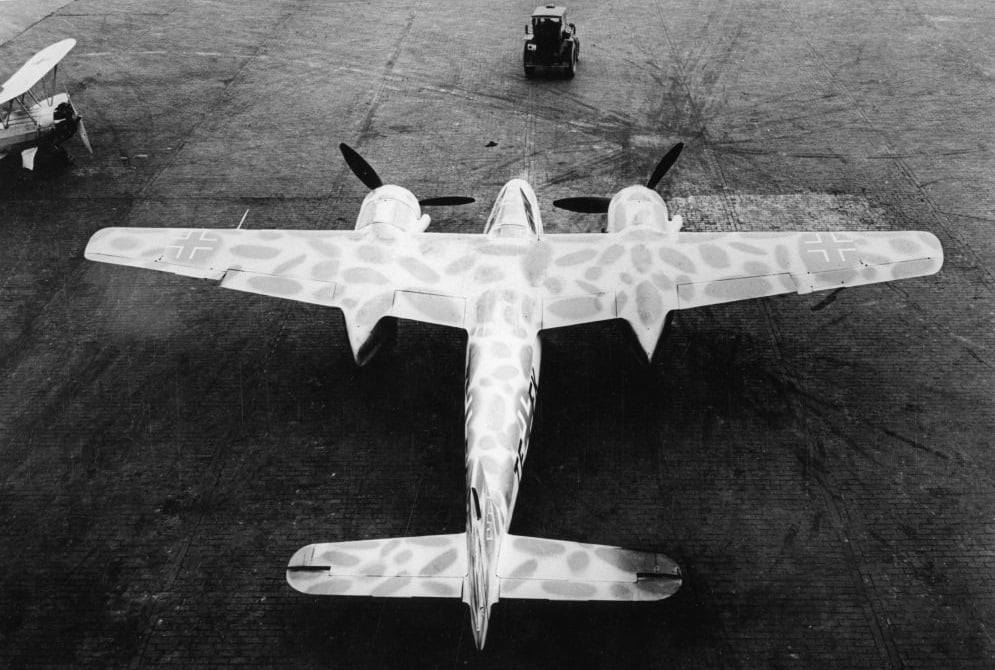

If one issue doomed the Ta 154 more than any other, it was glue. The British Mosquito owed its strength to reliable bonding resins and skilled craftsmanship. Germany, however, relied on a single factory producing the necessary synthetic adhesive. In May 1943, Allied bombers destroyed it.

The replacement glue provided by other firms was unstable—curing unevenly, absorbing moisture, and even eating away at the wood. The result was catastrophic. Several Ta 154s literally disintegrated mid-flight when their wings detached. Kurt Tank himself was accused of sabotage before a tribunal cleared him.

Cancellation and Obscurity

By 1944, Germany’s situation was dire. Bombing raids devastated production facilities, skilled woodworkers were scarce, and the Jumo 213 engines promised for the Ta 154 were redirected to other aircraft. With prototypes crashing, production collapsing, and confidence gone, Erhard Milch terminated the program in August 1944. He declared that not another drop of gasoline would be wasted on it.

In total, perhaps 30 to 50 Ta 154s were built. Only a handful reached operational night fighter units, and there is no evidence they ever flew combat sorties.