How Germany Salvaged Allied Planes and Turned Them Into Tools of Destruction

Photo by Umeyou, edited by World War Wings, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

During the Second World War, tens of thousands of Allied aircraft were shot down over Europe. Many of those wrecks did not simply lie forgotten in fields or forests. German recovery teams moved swiftly, gathering every usable part from Allied bombers and fighters. What followed was an industrial effort that turned wreckage into raw materials, spare components, and even fully reworked planes for use or study by German forces.

Salvage Teams in the Field

Once an aircraft was downed, German units known as Berge-Bataillone or salvage battalions arrived. They evaluated the crash site under fire, collected engines, propellers, radio gear and other valuable bits, and rushed what they could to nearby depots. In many cases the airframe itself was too damaged to fly again, but the aluminum skin, steel engine mounts, and electrical wiring were carefully shipped back to aircraft factories for melting, repurposing or rebuilding.

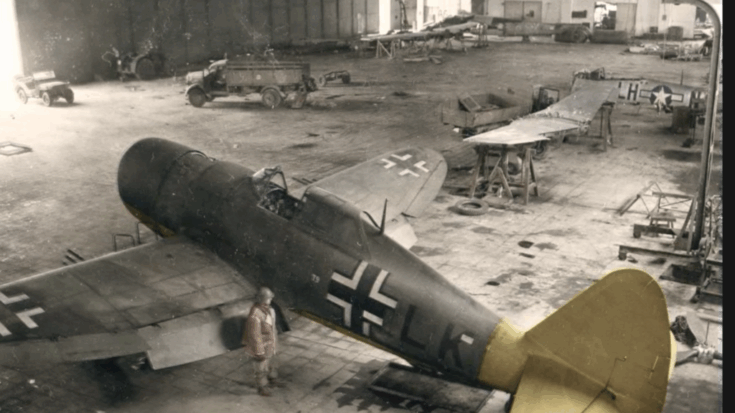

At the same time, other German specialist units such as Zirkus Rosarius tested captured Allied aircraft. This unit flew intact enemy fighters and bombers to study their performance and help German pilots learn how to counter them. The wreck-salvage work and captured-airplane testing were part of one system: salvage, recycle, test, adapt.

From Wreck to Factor

The process went like this: after a downed aircraft was found, the salvage team took off-site what they could. Technical gear like radios, cameras and guns were prioritized because these items revealed the enemy’s secrets. Structural parts followed: aluminum sheets, rivets, engine parts. These items were melted or refurbished. Some rare repairs turned whole aircraft or major components into usable spares or rebuild projects. For example, parts from P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts were reportedly reused in German overhauls.

This work helped fill gaps in Germany’s own production, especially as resources became scarce. By late in the war, German industries lacked raw materials, manufacturing capacity, and fuel. Salvaged Allied components were a small but useful supplement. But the salvage effort also exposed how stretched Germany’s logistics and industry had become. Author commentary noted that early in the war the German salvage units retrieved only about eight percent of crashed aircraft while other nations retrieved much more.

Turning Enemy Planes into Intelligence and Tools

Beyond scrap and parts, Germany also studied intact captured Allied planes. The Zirkus Rosarius unit flew these machines to learn their weaknesses. According to records, these captured aircraft were shown to German units to train them how to fight them. In many cases the aircraft were repainted in German markings and used in simulated combat. This provided direct feedback to German engineers and tacticians on how to counter Allied fighters and bombers.

At the same time, the salvage-and-rebuild program contributed to supply of spare parts for German forces. Planes shot down over the Reich or occupied territory were stripped, their guts sent to depots, melted down or rebuilt. This recycling helped Germany extend the life of worn aircraft and maintain operations despite declining production. Yet the need for salvage in such a broad scale also revealed the industrial disadvantage Germany faced: when you must pull enemy wreckage to feed your war machine, you are losing the ability to produce fresh on your own.

A War of Resources More Than Glory

What this effort shows is that the war in the air and on the ground was increasingly about machines, logistics and recovery. German forces that used salvage, rebuild and captured aircraft testing were acknowledging that attrition and resource shortage had overtaken earlier strategies of rapid maneuver and offensive dominance. The very fact that Germany had to rely on salvage of Allied wrecks underlines how the balance of production and resource management had shifted.

In a conflict where every plane, engine, gauge and bolt mattered, the salvaged remains of Allied aircraft became a hidden battleground. They were not merely trophies or scrap; they were materials, intelligence, and tools that extended Germany’s war efforts even in decline. What remains today is a reminder that behind every fighter and bomber lay scores of technicians, engineers and salvage crews working in mud, snow or rubble to keep machines flying, often in the shadow of defeat.