The Grim Truth Behind the High Death Toll of Hawker Typhoon Pilots

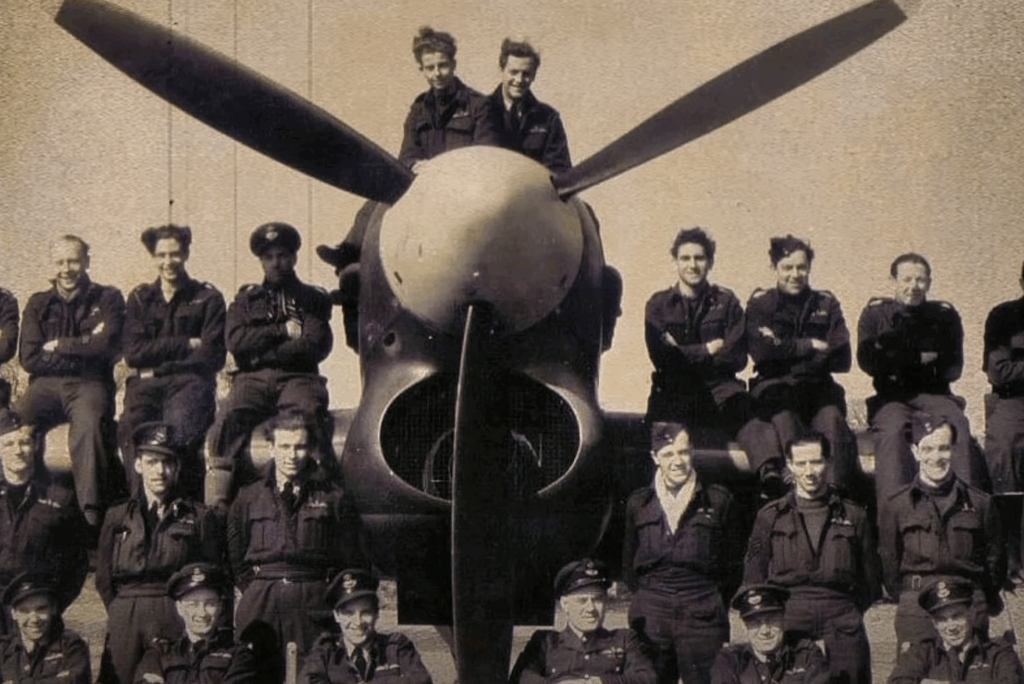

Unbelievable true stories / YouTube

A Fighter Built for a New War

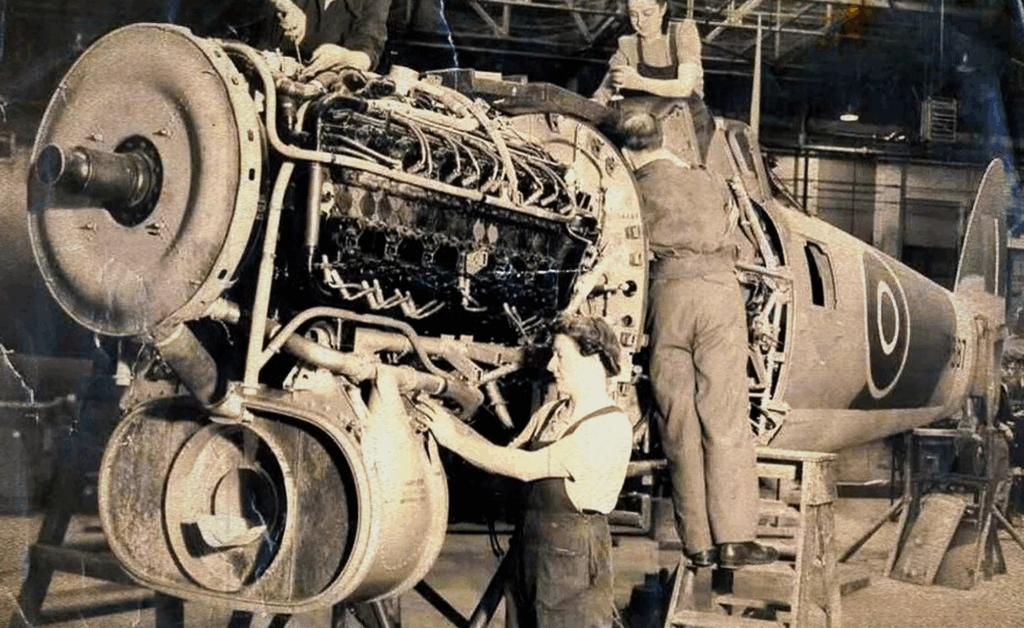

By the early years of World War II, the Royal Air Force was under pressure to keep up with rapid changes in aerial combat. The Hawker Hurricane, a key fighter during the Battle of Britain, was falling behind the latest German aircraft. To regain air superiority, especially with a future cross-Channel invasion in mind, Britain needed something faster and more powerful. That goal led to the creation of a new aircraft built around the Napier Sabre engine—one of the most powerful piston engines ever produced.

On paper, the Hawker Typhoon seemed like the answer. It was fast, heavily armed, and designed to be the next step in fighter development. But the real-world performance of the aircraft quickly revealed serious problems. Instead of dominating the skies, it became known for endangering its own pilots. Reports of mid-air failures, tail separations, and cockpit fires spread quickly. Many airmen began to view the Typhoon not as a lifesaving tool of war but as a flying death trap.

Unstable and Deadly

The Typhoon’s troubles began almost immediately during testing. In 1940, during an early flight, a structural flaw nearly led to disaster when the aircraft’s tail almost tore off mid-air. This forced emergency design changes. Yet even after modifications, problems kept showing up. When squadrons began switching from Hurricanes to Typhoons in 1941, they encountered new challenges. Most notably, the Napier Sabre engine had a bad habit of bursting into flames when started.

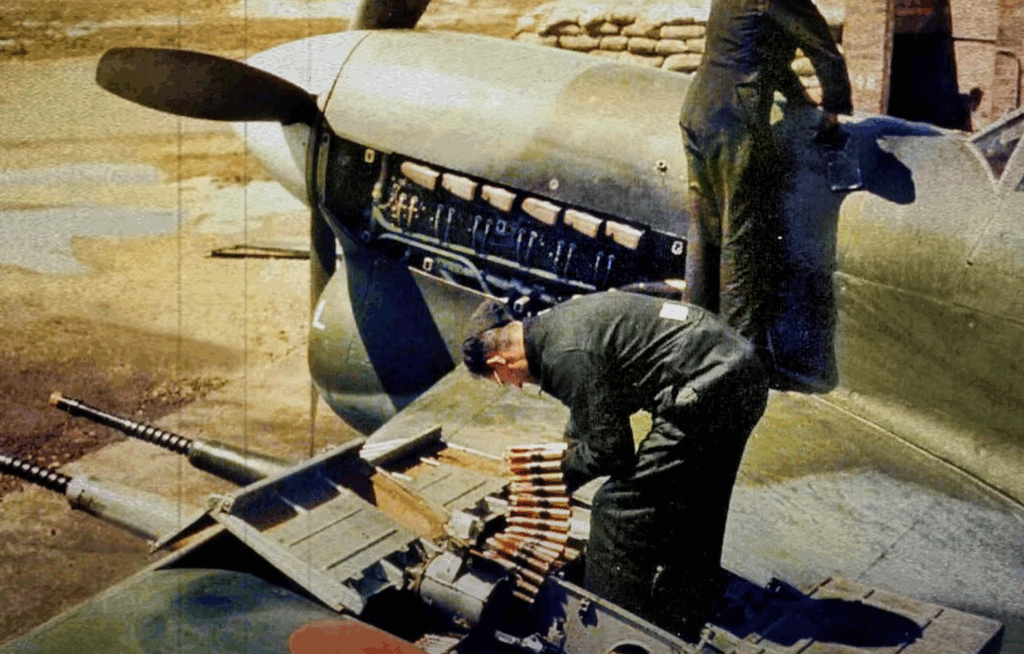

To get it running, ground crews had to fire explosive cartridges to turn the engine. If fuel was over-primed or temperatures weren’t right, the engine could ignite. Pilots were burned. Ground crews kept fire extinguishers on hand during every start-up. The Typhoon was powerful, but unpredictable, and it required more care than most wartime aircraft.

A Host of Dangerous Flaws

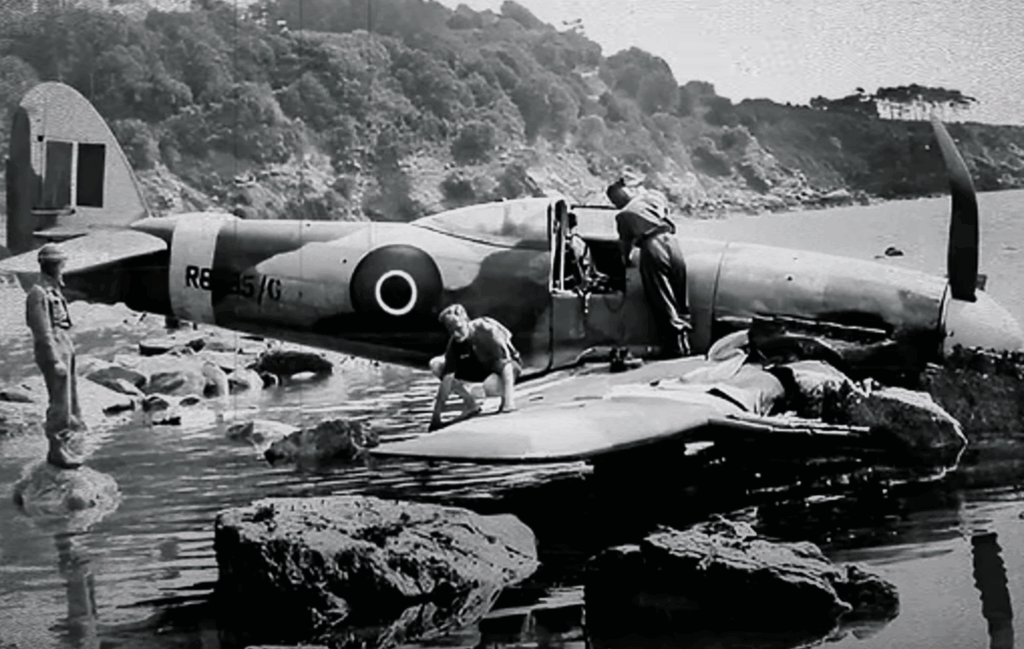

Mechanical fires weren’t the only risk. The exhaust system leaked carbon monoxide into the cockpit, leading to pilots passing out mid-flight with no warning. Others died when the tail section separated under stress. Escaping the aircraft during emergencies was also a challenge due to its car-style door, which often jammed during crashes or spins.

As more deaths occurred from design issues than combat, RAF commanders started to question the aircraft’s future. Morale among pilots dropped. The Typhoon had been built to be a high-speed interceptor but couldn’t safely perform the role. By late 1942, there was serious talk about cancelling the aircraft altogether.

From Near Cancellation to Sudden Comeback

However, just as the Typhoon was about to be pulled from service, a new threat gave it one last chance. The German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 had begun fast strike missions across the English Channel, evading most RAF fighters. The Typhoon, despite its faults, had the speed needed to catch them.

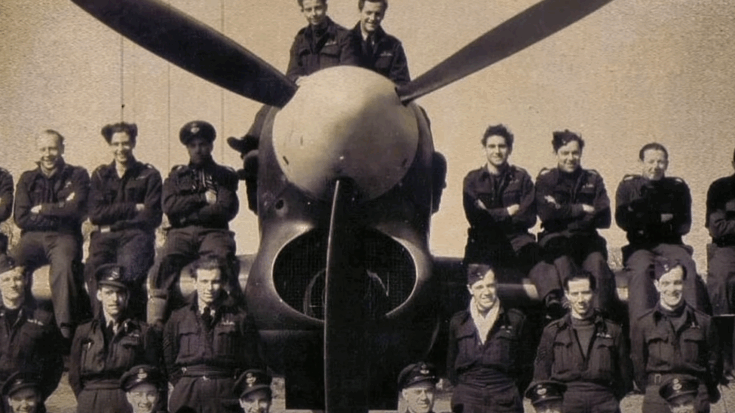

The aircraft underwent key upgrades. The canopy was changed to improve visibility and exit options. Oxygen systems were fixed, and only experienced pilots were assigned to Typhoon squadrons. This new approach began to pay off. The Typhoon started intercepting Fw 190s effectively, forcing German air raids to stop. A defensive line of Typhoon units stretched along Britain’s southern coast, controlling the skies above the Channel for the first time in months.

A New Role on the Front Lines

Despite its gains as a fast interceptor, the Typhoon would find its true value in a different role. RAF planners preparing for D-Day needed a plane that could strike targets in France quickly and powerfully. A young squadron leader named Dennis Crowley-Milling saw what the Typhoon could become: not just a fighter, but a ground attack aircraft.

The Typhoon was rearmed with rocket projectiles. These RP3 rockets were inaccurate but powerful. Fired in pairs from rails beneath the wings, they had enough explosive power to destroy tanks, supply trucks, and bunkers. What made the Typhoon so effective wasn’t just the weapons—it was the speed and low-altitude attack runs. Typhoons would fly low across the Channel to avoid radar, spot a target, dive in at full speed, fire their payload, and escape before enemy defenses could respond.

Changing the Course of the War

This shift turned the Typhoon into one of the most effective ground attack aircraft in the European theater. In the lead-up to D-Day, Typhoons knocked out radar stations, blocked transportation routes, and disabled enemy communications. Their attacks left German defenders slow to react when Allied troops landed on June 6, 1944. Though the Typhoon was never designed for this role, it filled it better than anyone expected.

The aircraft that had once caused panic on airfields became a key part of the Allied advance. By war’s end, Typhoon squadrons had destroyed more enemy vehicles than any other Allied aircraft in Europe. But its success came at a high price. Many of the young pilots who flew it never made it back—not because of enemy fire, but because the plane itself had failed them.