The Story of the Two Hungover Pilots Who Defended Pearl Harbor During WWII

Pearl Harbor National Memorial / YouTube

On the morning of December 7, 1941, a surprise attack by Japanese forces changed the course of American history. Among the chaos, two young U.S. Army Air Corps pilots in their early twenties—Lieutenant Kenneth Taylor and Lieutenant George Welch—reacted with speed and bravery. Still recovering from a long night out in Honolulu, the two officers had only just fallen asleep when they were jolted awake by the sounds of explosions and gunfire. Within minutes, they would become some of the first American pilots to fight back during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Taylor and Welch had spent the night before attending a formal event. By morning, they were still wearing tuxedo trousers when the first bombs fell. Their base at Wheeler Field was one of the initial targets, and the situation escalated quickly. With no time to waste, they contacted Haleiwa Field, a nearby auxiliary airstrip roughly ten miles away, and ordered their P-40B Warhawk fighters to be readied. They jumped into Taylor’s car and drove at high speed toward the airfield. Along the way, Japanese aircraft strafed the roads, but they pushed forward, determined to get airborne.

Flying Without Orders

When they arrived at Haleiwa, they found the strip intact. Without delay, they climbed into their aircraft. The ground crews had only managed to load .30 caliber ammunition, and the fighters weren’t fully fueled, but that didn’t stop the pilots. Despite being advised to space the planes out to avoid being destroyed together, Welch dismissed the idea, and they both launched into the air. This was done without any formal command—strictly against military procedure at the time.

Once airborne, the sky revealed the full scale of the attack. Waves of Japanese bombers and fighters were targeting American installations. Taylor and Welch climbed high, scanning for enemy aircraft. They spotted a group of dive bombers heading for U.S. targets and dove into action. Though outnumbered, they pressed the attack, shooting down several planes. During the fighting, Taylor’s aircraft sustained damage, and he flew back to Wheeler Field to reload. When he landed, the destruction at the base was even more apparent.

Ignoring Commands

While the ground crews worked quickly to rearm and patch up the aircraft, the officers on-site gave strict instructions not to take off again. A second wave of Japanese bombers had been spotted, and commanders feared more losses. Taylor and Welch, however, chose to ignore the orders. As more explosions rocked the airfield, they climbed back into their cockpits and took off once more.

In this second round of fighting, Taylor was already wounded from earlier gunfire. He still pursued a group of enemy bombers, only to be hit again in the leg and arm. Meanwhile, Welch continued engaging targets. At one point, Taylor found himself being chased by an enemy aircraft. Welch, seeing this, broke formation and fired at the attacker, downing it and helping Taylor survive. Despite their injuries and limited supplies, they remained in the air as long as possible.

Returning From the Fight

Eventually, Welch spotted another enemy bomber and brought it down before returning to base. Taylor, bleeding and flying a damaged plane, was also able to land safely. By the end of the attack, Welch had four confirmed kills. Taylor was credited with two confirmed and two probable. Their aircraft were in poor shape, but the pilots had survived and inflicted damage on the enemy, even as the larger battle overwhelmed American defenses.

Recognition and Aftermath

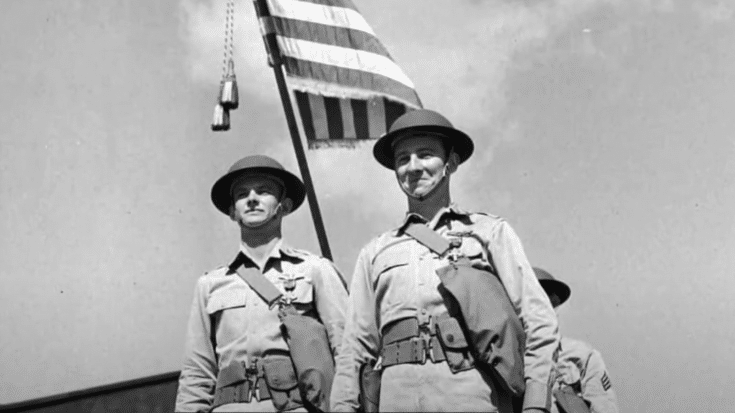

Their actions gained attention quickly. Interviews with Japanese pilots after the war confirmed that Taylor and Welch’s response may have prevented further losses at Haleiwa. However, their decision to launch without orders caused problems. While both were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Welch was denied the Medal of Honor, partly due to the lack of formal clearance to engage.

Taylor continued his service and retired in 1971, later passing away in 2006. Welch also stayed in aviation, eventually becoming a test pilot. He flew combat missions in Korea, even when not officially assigned to do so. In 1954, he died during a high-speed flight test. Both men left behind a story of quick thinking, risk, and bravery during one of the darkest mornings in U.S. history.