How a Farm Boy’s “Impossible” Trick Made Him Destroy 40 Japanese Planes… All Alone

YouTube / Echoes of War

September 1944, above Borneo. Major Richard Ira Bong eased his P-38 Lightning into a shallow dive, scanning the clouds for movement. Below, Japanese fighters climbed toward American B-24 bombers—unaware that one of the deadliest pilots in American history was positioning for the kill. By war’s end, this quiet farm boy from Poplar, Wisconsin, would achieve 40 confirmed aerial victories, making him the highest-scoring American ace of all time—a record that still stands eight decades later.

From Farm Fields to the Flight Line

Bong’s journey to the top didn’t begin with heroics—it began with trouble. In 1942, newly assigned to Hamilton Field, California, the young lieutenant nearly ended his career by performing unauthorized aerobatics over San Francisco. His commanding officer, General George Kenney, grounded him immediately—but instead of court-martialing him, Kenney saw raw talent worth saving. Bong possessed near-superhuman spatial awareness, lightning-fast reflexes, and uncanny control of his aircraft.

Kenney decided to train, not punish, the reckless young pilot. That decision would change the course of air combat in the Pacific.

Into Combat Over New Guinea

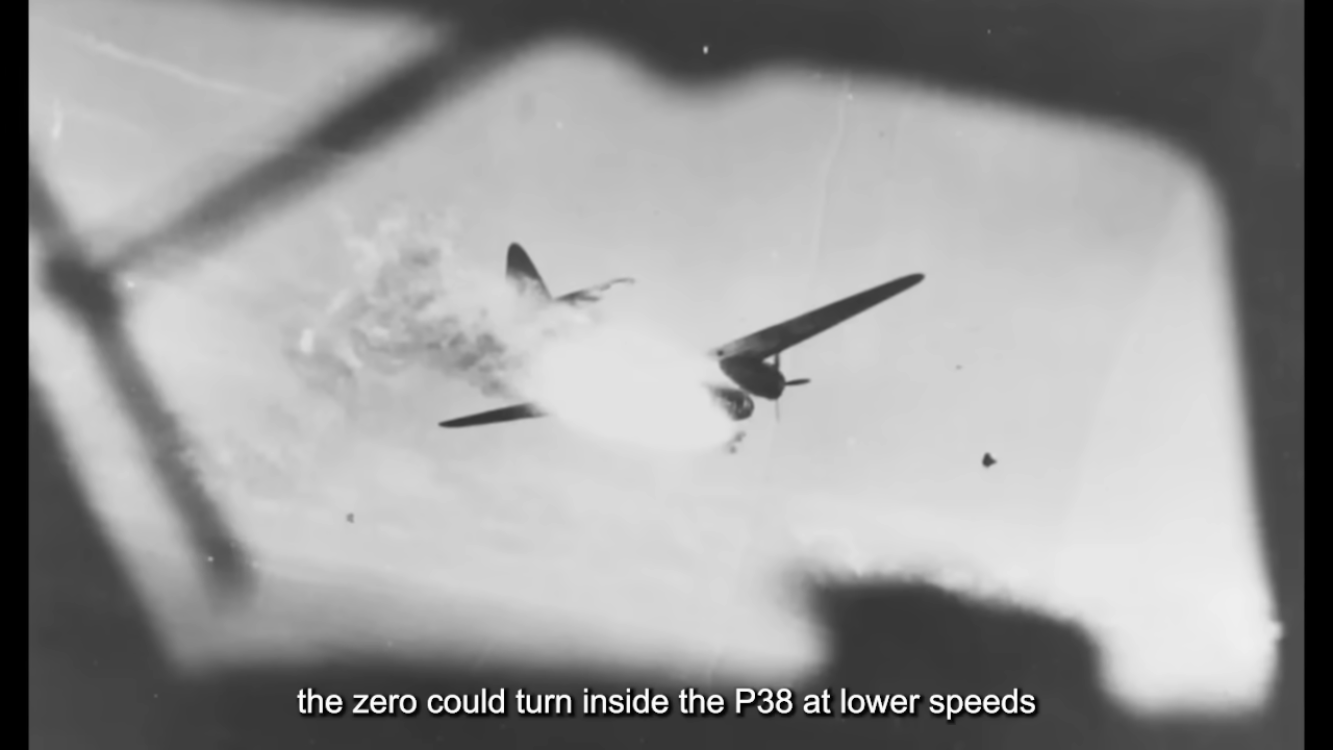

By late 1942, Bong joined the 9th Fighter Squadron in New Guinea. There, he faced Japanese Zero pilots hardened by years of combat. The odds were grim. The Zero could outturn nearly any Allied aircraft, and many American pilots died trying to match it in close combat. Bong learned fast: never turn with a Zero. Instead, he exploited his P-38 Lightning’s strengths—speed, altitude, and devastating nose-mounted firepower.

The P-38’s twin Allison engines gave it range and stability few fighters could match. Its four .50-caliber machine guns and 20mm cannon fired in a tight, lethal cone. When Bong’s aim was true, a single burst could obliterate an enemy plane.

Master of Deflection Shooting

What truly set Bong apart wasn’t aggression—it was precision. He mastered deflection shooting, the art of firing not where the enemy was, but where they would be. Few pilots could calculate these angles in the heat of battle. Bong did it instinctively.

He stalked his prey patiently, maneuvered into the perfect firing position, and unleashed short, controlled bursts. His gun camera footage showed minimal wasted ammunition—just calm, surgical efficiency. Squadron mates called him “the most patient killer in the air.”

Climbing the Ranks, Breaking Records

Through 1943 and 1944, Bong’s victories piled up. At Buna, Lae, and Hollandia, he perfected “boom and zoom” tactics—diving from altitude, firing with precision, and climbing away before the enemy could react. His P-38, painted with the name Marge after his sweetheart back home, became one of the most feared aircraft in the Pacific.

By mid-1944, Bong had surpassed World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker’s record of 26 kills. General Kenney, fearing the loss of America’s new hero, tried to pull him from combat. But Bong insisted on flying. Even when restricted to limited missions, he continued to rack up victories, shooting down veteran Japanese pilots over Borneo and the Philippines.

In one engagement, his P-38 was hit and lost an engine, yet he continued fighting on one engine—scoring another kill before limping home to base.

The Ace of Aces

By December 1944, Bong had reached 40 confirmed kills. General Douglas MacArthur personally approved his Medal of Honor, and Bong was permanently grounded—too valuable to risk. But his influence on aerial tactics endured. His disciplined approach—maintaining altitude advantage, using speed to strike, and firing only when certain—became standard doctrine for American fighter pilots.

New trainees studied his gun camera footage, learning how precision and patience could win battles that brute aggression could not.

A Tragic End and an Unbroken Record

In 1945, Bong transitioned to testing America’s first operational jet fighter, the P-80 Shooting Star. On August 6, 1945, during a routine test flight over Burbank, California, his jet suffered a catastrophic engine failure shortly after takeoff. Bong attempted to bail out but was too low. He was killed instantly—just hours before news broke that the atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima.

He was only 24 years old.

Legacy of a Legend

Today, at the Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center in Wisconsin, visitors can see his flight logs, Medal of Honor, and a restored P-38 Marge. His record of 40 victories remains unmatched in U.S. history.

Bong proved that true mastery in combat comes not from recklessness, but from patience, precision, and control. His “impossible” trick—deflection shooting—turned aerial warfare into an art form. Eighty years later, no one has surpassed America’s farm boy ace who destroyed 40 enemy planes—all alone.