How Japan Built the Largest Submarines of WWII With Hidden Aircraft Hangars

Drachinifel / YouTube

A New Type of Weapon

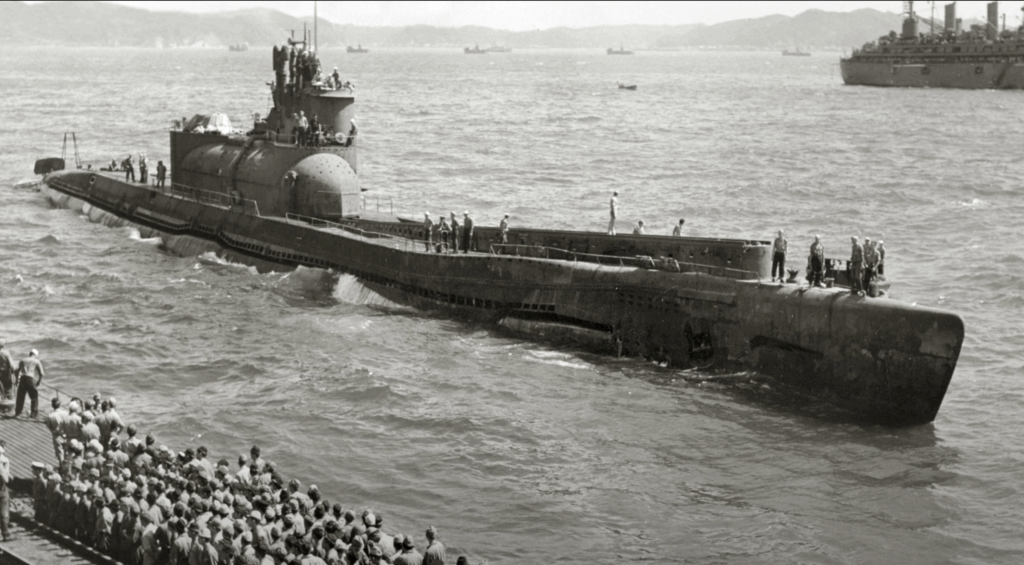

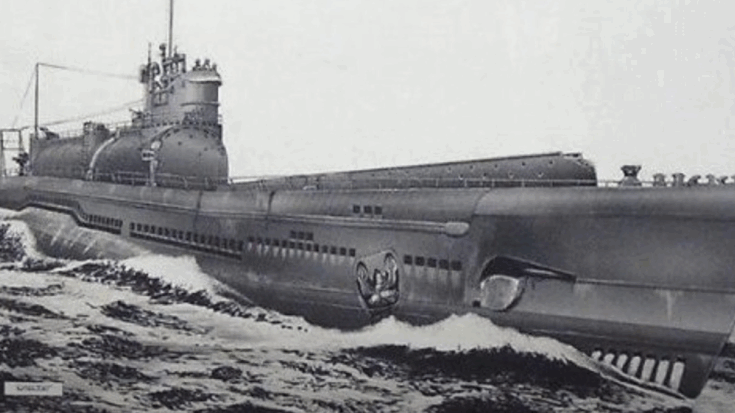

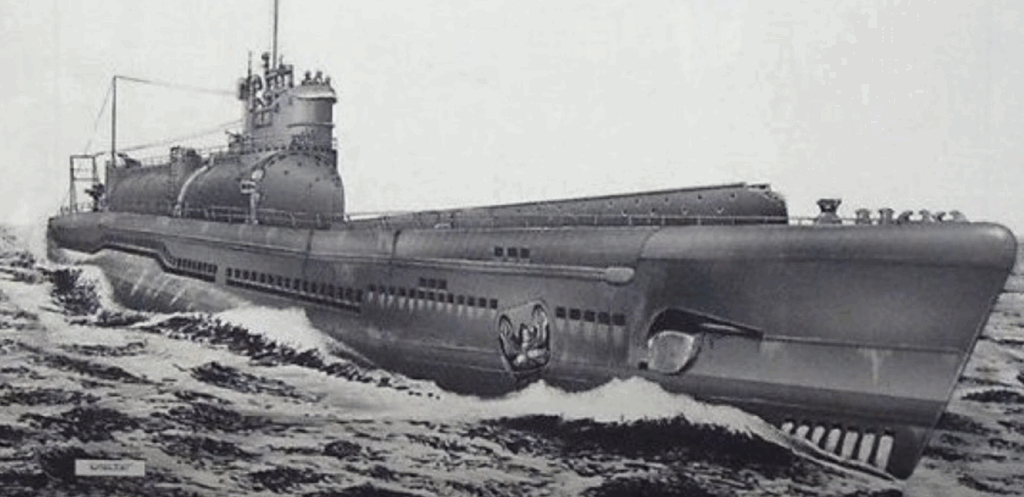

In the closing years of the Second World War, Japanese naval leaders searched for ways to strike far beyond the Pacific battlefield. Their answer was the I-400 class submarine, the largest ever built during the war. Unlike ordinary submarines, these massive vessels were designed to carry aircraft inside a long hangar mounted on the deck. For this reason, many observers later called them “underwater aircraft carriers.” The concept combined two ideas: the stealth of a submarine with the long-range striking power of carrier-based planes.

The intention was bold. By using these submarines, Japanese forces hoped to sail across the ocean unseen, surface near an important target, launch aircraft for surprise bombing raids, and then disappear beneath the waves. Targets considered included the Panama Canal, which was vital for American shipping, and later large naval bases in the Pacific. In theory, these missions could disrupt supply lines or damage American fleets.

Size and Design

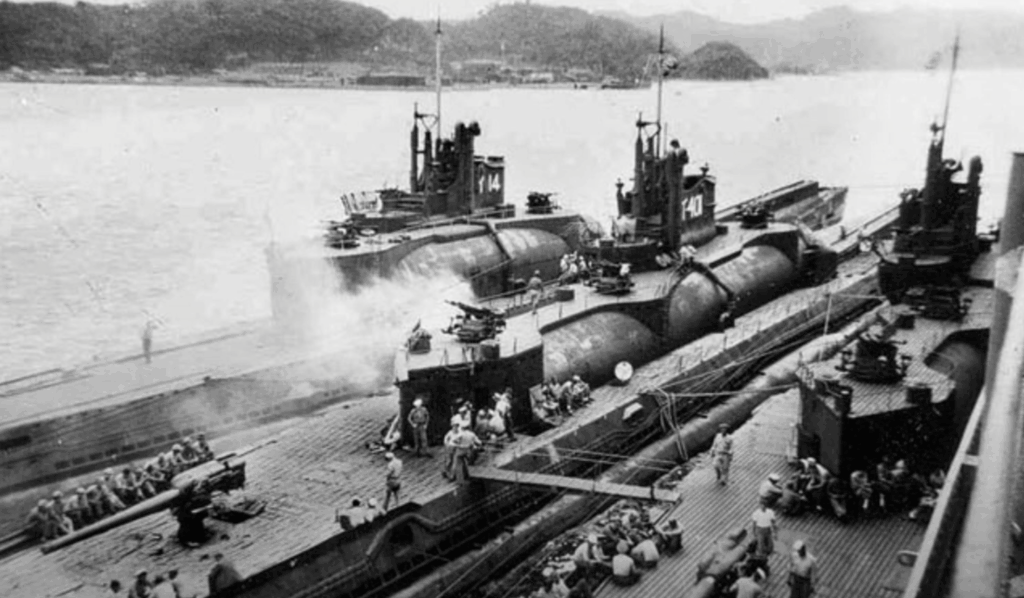

The I-400 class submarines were extraordinary in scale. Each stretched more than 400 feet, about twice the length of most wartime submarines. Their crews numbered over 140 men, supported by supplies that could sustain months-long voyages. Their range was remarkable, able to travel around the globe without refueling.

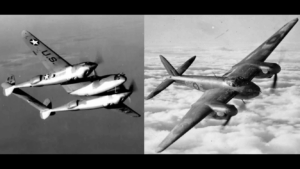

Most striking was the aircraft hangar, a cylindrical chamber large enough to hold three specially built planes known as Aichi M6A1 Seiran. These aircraft were designed to fit inside the hangar with wings folded and floats detached. Once surfaced, the crew could roll them out, assemble the wings, and launch them from a catapult on deck. After missions, the planes were intended to land on the sea, where cranes would hoist them back aboard.

Life on Board

Despite their size, life inside was difficult. The crew lived in cramped, hot, and noisy conditions. Air was often stale with the smell of fuel and machinery, and food supplies grew unpleasant after weeks at sea. Sailors slept in shared bunks, and the constant fear of enemy detection weighed heavily. Missions could last months, cutting men off from the outside world. The submarines were impressive machines but harsh environments for human endurance.

The Seiran aircraft themselves were versatile, capable of carrying bombs or torpedoes. However, they were not as fast or powerful as American fighters, leaving them vulnerable in combat. The process of preparing and launching them was slow. The submarine had to remain surfaced for extended periods, exposing it to attack before the planes could even take off.

Strategic Ambitions

Japanese planners considered ambitious operations for these submarines. Early proposals focused on the Panama Canal. Destroying the locks there would have forced American shipping to detour around South America, adding weeks to supply routes. Later, plans shifted to American naval bases in the Pacific, particularly Ulithi Atoll, a major anchorage filled with carriers and warships. A successful raid could have inflicted damage, but timing and resources worked against the plan.

In practice, the submarines faced serious challenges. They were slow to dive and vulnerable to detection. Mechanical issues were frequent, and the launch sequence left them exposed. By the time the I-400 class was ready in 1945, American forces dominated the seas and skies. Intelligence breakthroughs also revealed Japanese movements, removing any chance of surprise.

Fate of the I-400 Class

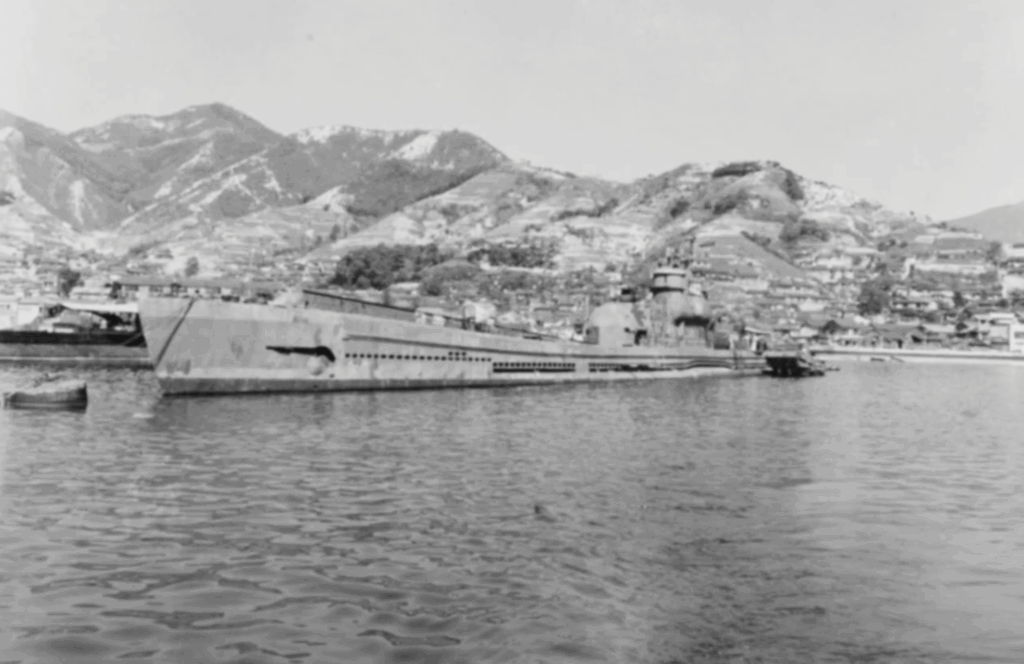

Only three of these giant submarines were completed before the war ended. They never carried out a combat mission. Japan surrendered in August 1945, and the vessels were handed over to American forces. Sailors who inspected them were astonished at their size and concept.

The U.S. Navy studied the submarines closely, examining their systems and the Seiran aircraft. But soon a new concern arose: the Soviet Union, now an ally at war’s end, requested access to the captured technology. To prevent this, the U.S. secretly scuttled the submarines off Hawaii in 1946. For decades they rested on the seabed, largely forgotten until undersea explorers rediscovered them in modern times.

Today, the I-400 class remains a symbol of wartime ambition and desperation. These submarines reflected Japan’s effort to change the course of the war with bold engineering. Though they never fulfilled their intended role, they stand as a reminder of how far nations were willing to go in search of advantage during the most destructive conflict in history.