How Japan Tried to Clone the B-17 But It Couldn’t Even Get Off the Ground

Unforgettable Stories / YouTube

The Dream of a Fortress

Tokyo, 1942. The Pacific War was in full force, and Japan sought to build an aircraft as powerful as America’s B-17 Flying Fortress. The B-17 had already proven itself as a heavy bomber that could cross oceans, withstand massive damage, and still return home. Japan’s air fleet, though formidable in short-range combat, lacked a bomber capable of long-distance strikes. Their aircraft were light and efficient but fragile, designed for limited operations rather than large-scale bombing campaigns.

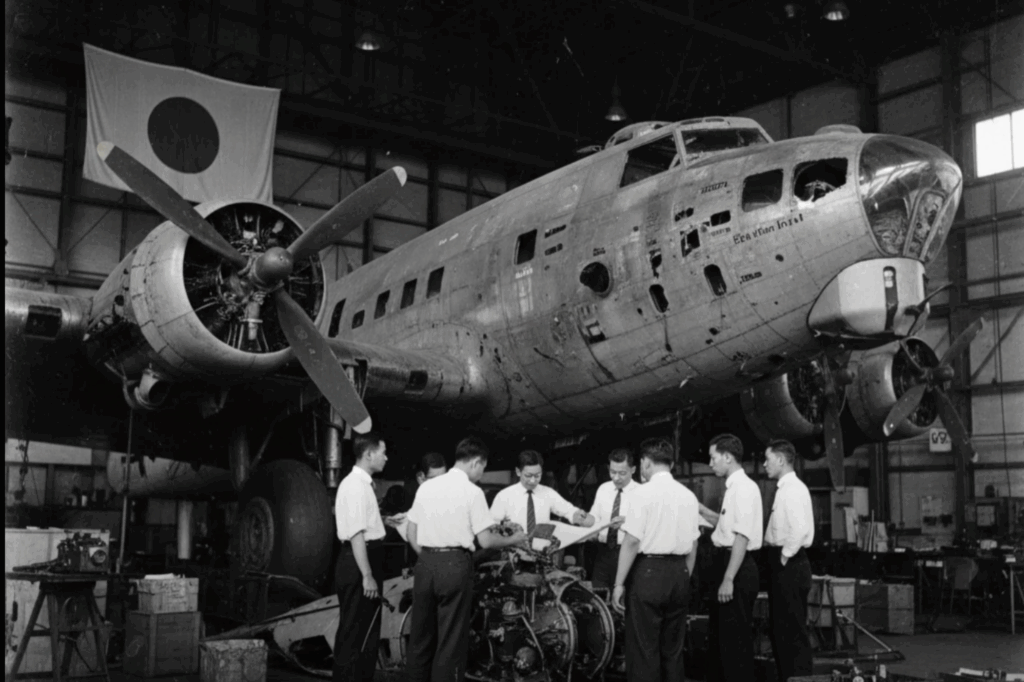

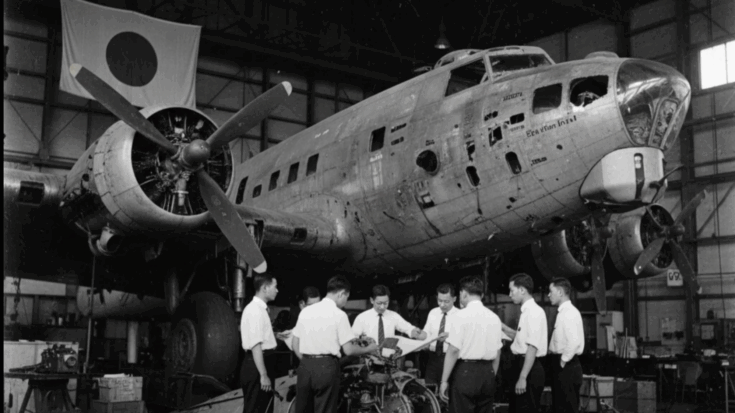

When Japanese forces captured damaged B-17s in the Philippines and Java early in the war, their engineers saw an opportunity. They brought the wrecks to Tokyo’s Tachikawa Air Arsenal, hoping to understand the American design. The B-17’s complexity shocked them. Its four Wright Cyclone engines generated more power than any Japanese engine could at the time, and its reinforced aluminum structure required precision machinery Japan did not possess. Still, military command insisted they copy it. Thus began Japan’s secret effort to create their own “flying fortress.”

The Birth of the Kawasaki Ki-91

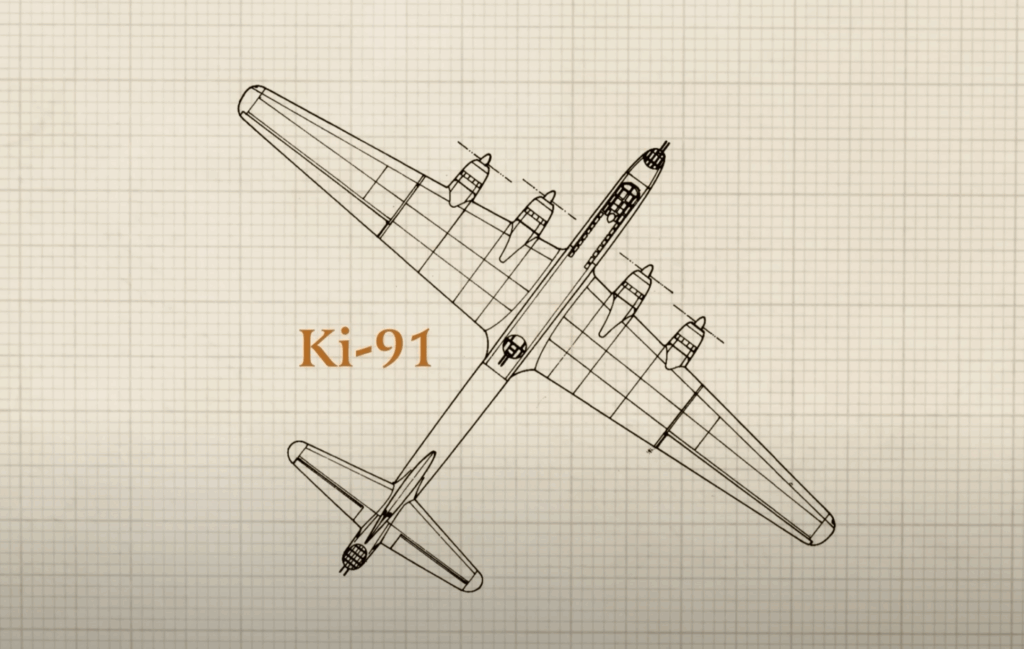

In 1943, engineers at the Kawasaki Aircraft Company were ordered to begin work on what would be called the Kawasaki Ki-911. They studied every inch of the captured B-17s, trying to replicate its systems using limited resources. The task quickly proved overwhelming. The aircraft’s American-made engines were far too advanced, and Japan’s equivalent, the Mitsubishi HA-104, produced less power. That shortfall alone meant their bomber would struggle to even take off once fully loaded.

Despite the odds, engineers persisted. Inside freezing hangars, they drew blueprints on rice paper and built prototypes from salvaged materials. Progress was painfully slow. Factories were bombed, steel and fuel were scarce, and many skilled workers were sent to fight at the front. When the Ki-91’s structure was nearly complete, Japan’s industrial base was collapsing. In early 1945, before the prototype could fly, Allied bombers destroyed the Kawasaki plant. The aircraft—Japan’s attempt at a fortress—was reduced to rubble. As one engineer later said, “We wanted a fortress, but we built a tomb.”

The Shadow of the Superfortress

By 1944, the B-17 was no longer the greatest threat in the sky. The United States had introduced the B-29 Superfortress, a bomber so advanced that Japan could hardly believe it existed. The B-29 flew higher, carried heavier loads, and used engines with turbo-superchargers—technology far beyond Japan’s capabilities. Still, the Japanese military launched another desperate program, this time led by the Nakajima Aircraft Company.

This new design, called the G8N Renzan, was meant to match the B-29. Engineers studied every wrecked American bomber they could find, trying to piece together how such machines were built. But shortages of material and precision tools crippled the effort. They substituted lighter engines, simplified the fuselage, and removed armor to save weight. The prototype flew in late 1944, but its performance was disappointing. It was underpowered, slow, and overheated easily. Not long after, American raids destroyed Nakajima’s Musashino plant, ending the project before it could advance.

A War Lost in the Skies

As Japan’s war effort collapsed, the real B-29s continued to bomb cities across the country. Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya were reduced to ashes. By August 1945, the B-29 Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, ending both the war and Japan’s dream of rivaling American air power. When Allied forces occupied Japan, they discovered hangars filled with incomplete bombers, burnt blueprints, and broken engines. Every secret project—the Ki-91, the Renzan, and others—was seized or destroyed.

For years, Japan’s skies were silent. Aircraft production was banned, and engineers turned to building bicycles, cars, and sewing machines. Yet their skills didn’t vanish—they evolved. By the 1950s, when Japan was allowed to produce planes again, the same companies that once built bombers—Mitsubishi, Kawasaki, and Nakajima (renamed Fuji)—returned to aviation, this time working with the United States.

From Imitation to Innovation

By the 1970s, Japan’s engineers were no longer imitators. They had become leaders in precision manufacturing, helping design and build parts for Boeing and Airbus. The failures of the 1940s became lessons that shaped a new generation of technology. In museums today, the remains of the captured B-17s still rest in silence. Students and engineers visit them not as relics of defeat, but as symbols of how ambition, even when it fails, can lead to progress.