Why Nearly Every Japanese Aircraft Carrier Crew Was Wiped Out

The Second World War Tales / YouTube

A Fleet Doomed by Numbers

By August 1945, an astonishing 91% of Japanese aircraft carrier crew members were dead. For every hundred men who had served aboard, only nine survived the war. The Imperial Japanese Navy began with ten fleet carriers, but none remained afloat when the conflict ended. This was not only the result of battles but of decisions that left the force mathematically doomed.

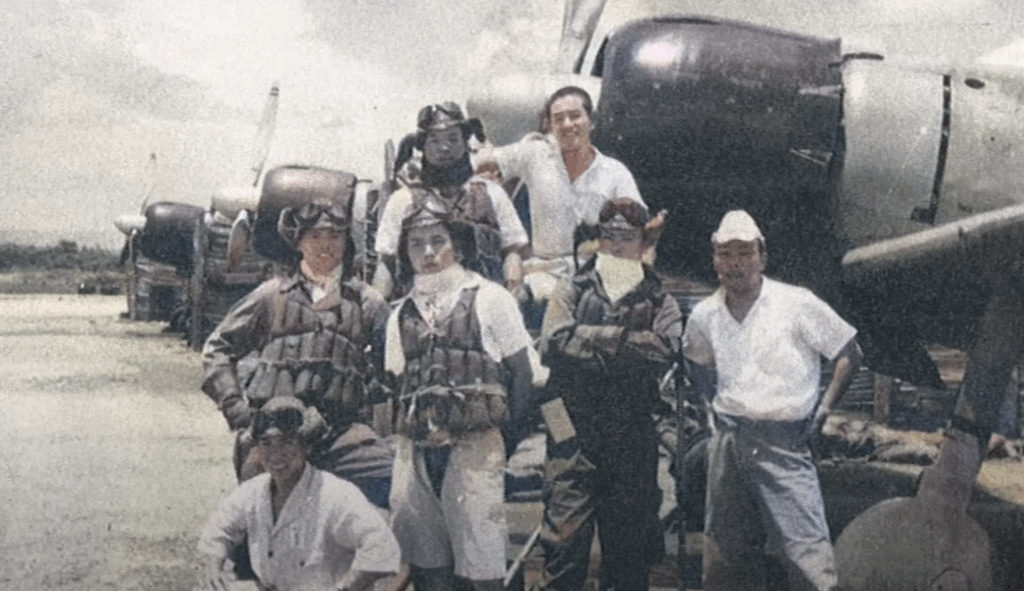

Japan entered the war with the finest naval aviators in the world. Each carrier pilot had received more than 800 hours of training. By 1944, the situation reversed. New recruits sometimes received fewer than 50 hours. The reason was simple: experienced pilots were never rotated home to train others. They remained in combat until they were killed, and without veterans to pass on their skills, training collapsed.

Midway and the Arithmetic of Defeat

The turning point came at Midway in June 1942. Four Japanese carriers and more than 300 aircraft were lost. The greater blow was the death of over a hundred highly trained pilots, each representing years of investment. Japan could replace them at a rate of about 200 per month, while the United States produced over 2,500 in the same time. The imbalance meant the carrier arm was already broken long before its leaders admitted it.

At the same time, the carriers themselves were vulnerable by design. Japanese naval doctrine emphasized offensive spirit over defensive preparation. Crews received little training in damage control. While American sailors attended firefighting schools, Japanese carriers relied on simple equipment. When the carrier Taiho was struck by a torpedo, ventilation systems spread fuel vapors through the ship. Hours later, one spark ignited the vessel and destroyed her with most of her crew.

Death Traps at Sea

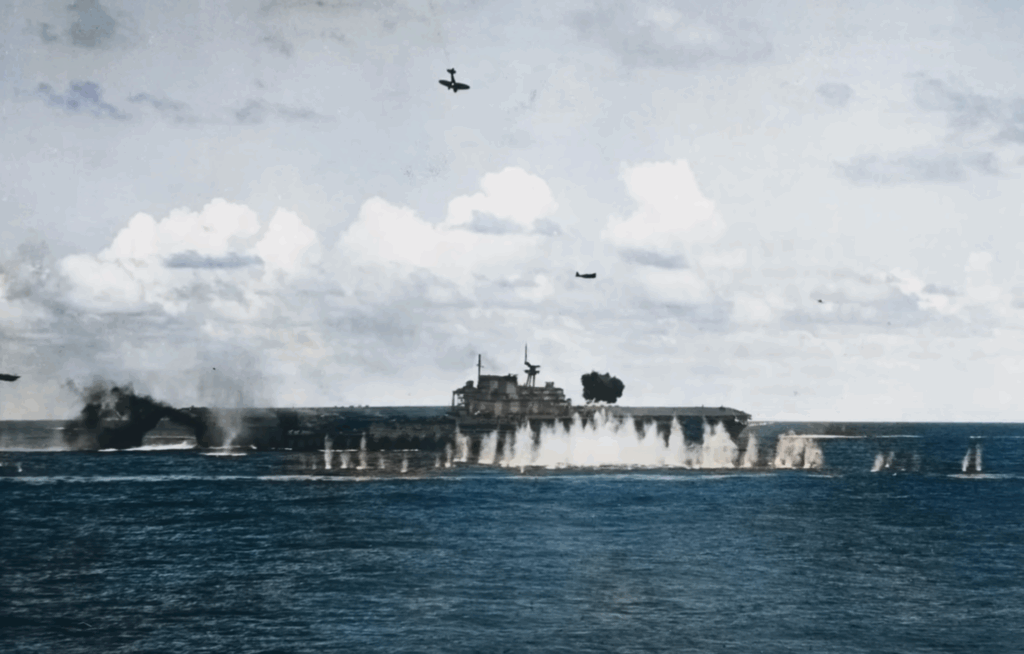

Survivors of other sinkings described how easily their ships were lost. A sailor from the carrier Shokaku recalled how three bombs from American dive-bombers struck, and within 20 minutes the vessel and 1,360 men were gone. Fires spread to the sea itself, burning those who jumped into the water. Such losses were not isolated tragedies but repeated patterns.

The carriers were overcrowded with aircraft. The Akagi carried more than 90 planes in space designed for 60. A single bomb in the hangar could destroy dozens at once, triggering explosions that spread uncontrollably. At Midway, the carrier Kaga was struck by four bombs, and in only nine minutes, 711 men were dead as the hangar turned into a furnace of aviation fuel and flames.

Technology and Industry Against Spirit

Another flaw was the lack of radar-directed anti-aircraft weapons. Japanese ships relied on visual aiming against aircraft traveling at over 400 miles per hour, giving them a hit probability of only 2%. American carriers, using radar-guided guns, reached nearly 18%. The difference turned battles into one-sided encounters where courage could not compensate for technology.

Japan’s industrial limits sealed its fate. After Midway, six carriers remained. In the following years, Japan managed to build seven more, while the United States launched 90. In 1944 alone, America completed 19 new fleet carriers, compared to a single Japanese launch. The imbalance between factories and shipyards meant the outcome was decided before many later battles began.

The Collapse of Training and the Final Blows

As the war dragged on, pilot training grew worse. By 1944, American pilots logged 300 hours, including advanced time in operational aircraft. Japanese recruits received as little as 30 hours, often in gliders. Many could not land on carriers even in calm seas, much less during battle. At the Battle of the Philippine Sea, often called the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, Japan lost three carriers and 400 planes. Only 43 pilots survived, while the United States lost just 29 aircraft.

Captured officers later admitted they understood their fate after Midway. Every carrier mission afterward was effectively a suicide assignment, even if it was not called that at the time. The giant carrier Shinano, the largest ever built at 72,000 tons, was sunk on her maiden voyage by four torpedoes from a single submarine. Over 1,400 men were lost because the crew had never been trained to use the ship’s damage control equipment.

The Last Carriers and the End of a Force

By 1945, the final Japanese carriers were converted from battleships or passenger liners. Pilots assigned to them often could not land on their decks, making them little more than one-way launch platforms for suicide missions. The last operational carrier, the Amagi, was destroyed at anchor, with its crew still waiting for aircraft that no longer existed.

From the war’s beginning to its end, Japan trained about 3,500 carrier pilots. When the fighting stopped, only 112 were still alive. More than 25,000 sailors had died aboard carriers that had once represented the cutting edge of naval warfare. The doctrine of offensive spirit could not overcome the arithmetic of industry, training, and technology.