Why Japan’s Top Pilots Feared This One Allied Plane More Than Any Other in WWII

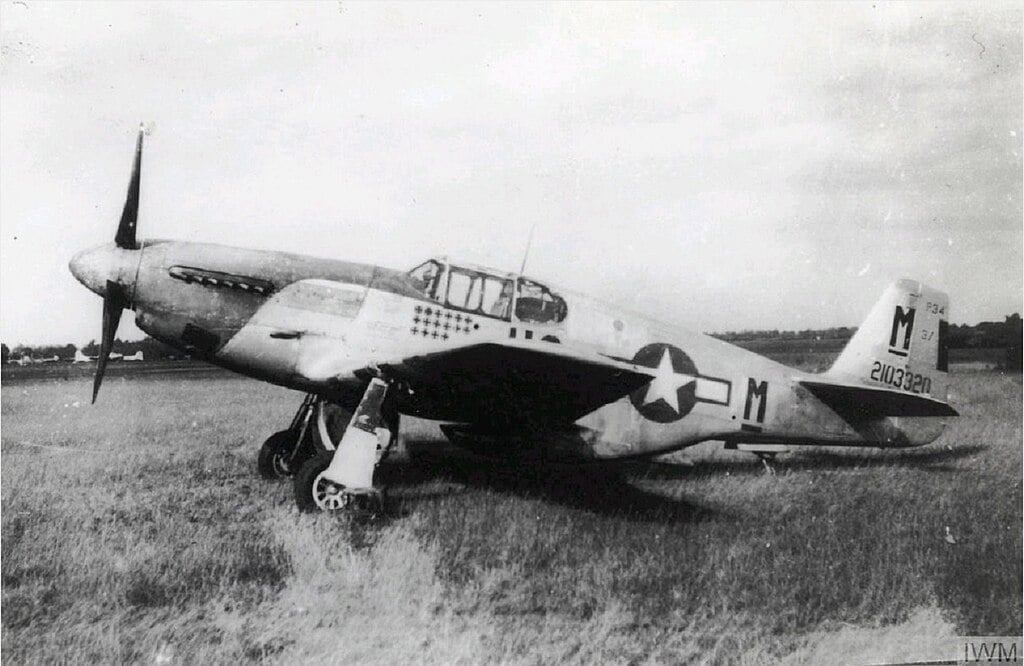

Photo by Imperial War Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Arrival of a Phantom Over Tokyo

In the closing months of World War II, the Japanese air service believed their homeland was untouchable. They were confident that no single-engine American fighter could reach the skies above Tokyo. But on April 7, 1945, that belief collapsed. As Japanese pilots scrambled to intercept the massive B-29 bombers, they saw something impossible—sleek, single-engine fighters weaving among the bombers. They were P-51 Mustangs, American aircraft that had somehow crossed 750 miles of open ocean from the island of Iwo Jima.

For Japanese pilots, the sight was like seeing a ghost. Their leaders had sworn such a flight could never happen. Yet there they were—fast, agile, and relentless. Flight Sergeant Totaro Shimezu later said, “When I saw the Mustangs with my own eyes, I thought I was dreaming. Our commanders told us no American fighter could reach Japan.” That disbelief quickly turned into fear.

The Power Behind the Mustang

The key to this impossible feat lay beneath the Mustang’s smooth metal skin. It was powered by the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, built under license in the United States by Packard. Earlier Mustangs used Allison engines that struggled at high altitudes, but the Merlin changed everything. Its two-stage, two-speed supercharger allowed it to maintain full power even where the air was thin. While Japanese engines gasped for oxygen, the Merlin kept breathing strong at 30,000 feet.

This engine, combined with the Mustang’s efficient laminar-flow wings, made the P-51 fast and fuel-efficient. With drop tanks attached, it could fly more than 1,500 miles—enough to escort bombers to Tokyo and back. Japanese fighters like the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate were excellent on paper, but Japan’s factories were running out of quality materials. Engines failed, parts didn’t fit, and poor fuel quality destroyed performance.

Factories, Fuel, and the War of Systems

While Japan struggled to build a few hundred aircraft, American factories rolled out new Mustangs every hour. Standardized production meant every part was interchangeable, and pilots could switch planes with complete confidence. In contrast, Japanese pilots often didn’t know if their aircraft would survive takeoff.

Training was another world apart. American pilots logged hundreds of flight hours before combat, mastering gunnery and formation tactics. Japanese recruits, by 1945, were rushed into battle with barely fifty hours of flight time. Many had never fired their guns in practice.

A Sky Owned by the Mustang

When the two forces met over Tokyo, the results were devastating. The Mustangs were faster by nearly 100 miles per hour and carried six .50-caliber machine guns with thousands of rounds. Japanese pilots had heavier cannons but little ammunition. Once they fired their brief bursts, they were defenseless. On that first day, American pilots destroyed twenty-six Japanese aircraft while losing only two of their own.

For Japan’s airmen, the sight of P-51s soaring freely above the homeland shattered morale. Captain Yoshio Yoshida wrote in his diary, “The appearance of American fighters over Tokyo has broken our spirit completely. We can no longer defend the emperor when the enemy rules our skies.”

In that moment, the P-51 Mustang was more than just an airplane—it became the symbol of a war already lost, the machine that proved no empire, however proud, could withstand the full force of industrial power and human determination.