The Fate of Kamikaze Pilots Who Chose Not to Complete Their Missions

Unauthorized History of the Pacific War Podcast / YouTube

Introduction to a Deadly Strategy

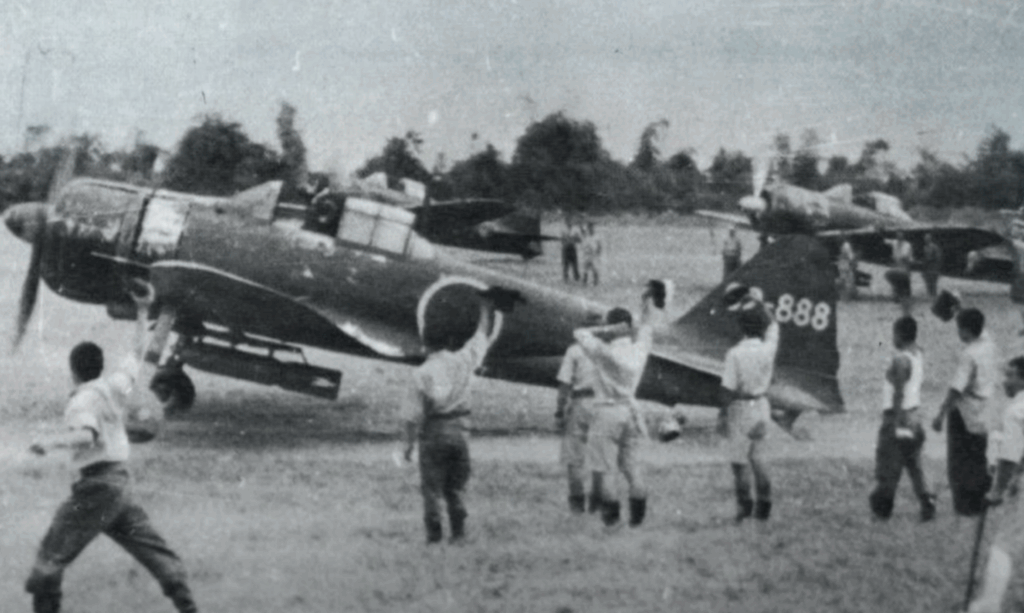

In late 1944, Japan faced growing losses across the Pacific. American forces were closing in, and Japan’s air attacks were no longer as effective. In response, military leaders created a new tactic—sending skilled pilots on one-way missions. These pilots were ordered to crash into Allied ships, turning their planes into flying bombs. The idea was to cause maximum damage and to scare the enemy by showing that Japan had soldiers willing to die without hesitation.

The word “kamikaze” means “divine wind.” It referred to typhoons that had once protected Japan from foreign invasion. But the pilots were not random recruits. They received special training and better food to prepare them both physically and mentally. They wrote farewell letters and were told they were doing something noble. Many believed this completely. But not everyone could follow through.

Fuel Myths and Mission Realities

There is a common myth that kamikaze planes were only given half a tank of fuel to stop pilots from returning. This was false. Full fuel tanks were needed to reach the targets, and Japan couldn’t afford to waste planes. If something went wrong—like bad weather or a technical problem—pilots were expected to come back. These men were not punished, because Japan could not afford to lose skilled airmen over issues beyond their control.

Sometimes pilots would return claiming they couldn’t find their targets or that enemy resistance was too strong. While these stories raised questions, they were often believed. In most cases, the pilots were simply told to try again. It was only in very rare cases—like a pilot returning nine times—when punishment became severe. That pilot was eventually executed, but this was not common.

Repeated Attempts and Group Strategy

To limit the number of pilots turning back, Japan began launching group attacks. This made it harder for anyone to leave the mission unnoticed. Alcohol was sometimes given before flights to reduce fear and hesitation. While some returned multiple times, many were simply reassigned or allowed to try again. The military chose practicality over harsh discipline.

The goal was to keep pilots alive long enough to complete a mission, not to waste them over mistakes. This approach showed that, while the kamikaze idea was deeply tied to national pride and sacrifice, it was still managed like any other military strategy. Japan needed trained airmen more than it needed examples made through punishment.

The Emotional Cost for Survivors

One part of the story rarely discussed is what happened to those who survived. Imagine living with the knowledge that you were meant to die for your country—but didn’t. Some pilots carried deep shame or guilt, feeling they had failed their duty and let down their families. Others may have felt relief but struggled with those emotions in silence.

Most of these feelings were not recorded, but the psychological stress must have been great. Young men trained to see death as an honor were left trying to live with the results of their survival. These emotional effects were part of the war, even if they weren’t talked about much.

War’s Harsh Reality Behind the Scenes

By 1944 and 1945, Japan was running out of nearly everything—fuel, planes, experienced pilots, and time. The idea of punishing pilots for failing suicide missions made little sense. Japan needed every person it could use. In the end, the kamikaze strategy—though wrapped in talk of honor—was run like a resource. The goal was to use it efficiently, not perfectly.

While many young men did crash into enemy ships, the ones who came back were rarely punished. They were seen not as cowards but as tools still useful to the war. This lesser-known side of the kamikaze program shows how even the most extreme plans were shaped by real-world problems, not just ideals.