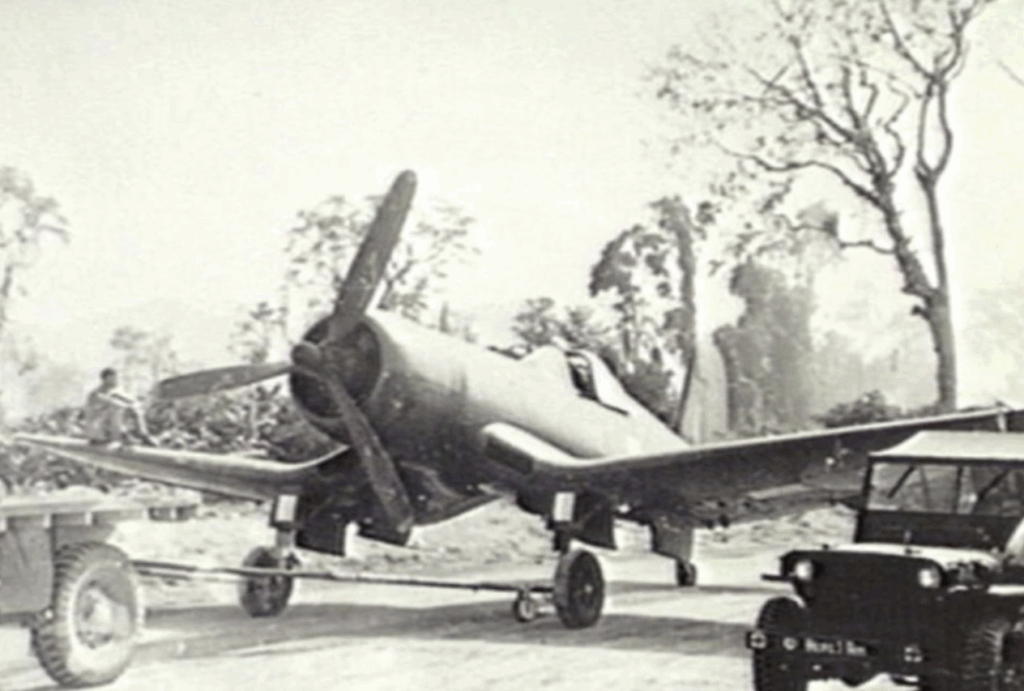

How One Marine’s Insane Gun Mod Turned His Plane Into a Flying Death Machine

Photo by Texasmorrell, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Trouble Above the Solomons

September 16, 1943, the air over Bougainville was alive with heat and gunfire. A Marine F4U Corsair raced through the sky, its six .50 caliber machine guns blazing. Captain James Sweat aimed at a twisting Japanese Zero, but his bullets missed. Moments later, his wingman’s plane spiraled down in smoke, swallowed by the jungle. That week, the squadron had already lost three aircraft—not to skillful enemies or engine failure, but to wasted ammunition.

The Corsair was powerful, fast, and capable, yet early combat showed it could not live up to its potential. Marine squadrons across the Solomon Islands struggled with poor accuracy. Pilots fired hundreds of rounds per enemy aircraft with little to show. The guns worked, the ammunition was reliable, and the pilots were among the best, but the bullets seemed to avoid their target. Gun camera footage revealed a strange pattern: tracers forming cages of fire around enemy fighters, but never connecting.

The Phantom Range

The problem lay in gun harmonization, the factory-set angles of the six machine guns on each Corsair. All guns were aimed to converge at a single point 1,000 feet away. On paper, this allowed pilots to lead and aim carefully. In practice, however, enemy aircraft moved too quickly, weaving and climbing, while the Corsair itself jolted with engine torque and recoil. By the time the bullets met, the target had moved. Pilots called this the Phantom Range: a deadly crossfire that hit nothing.

Squadrons like VMF-213, the Hellhawks, reported some of the worst hit ratios in the Pacific. Pilots returned from missions with empty belts and no kills. The official order from Marine Aircraft Group 11 forbade adjusting the convergence point, warning that going below 500 feet risked structural damage. The pilots continued to miss. Japanese forces noticed and began deliberately drawing Corsairs into ineffective long-range fire, waiting for them to empty their guns before counterattacking.

McCarthy’s Observation

In a maintenance tent near Tirokina Airfield, Staff Sergeant Michael McCarthy, a 26-year-old ordinance man, saw something others missed. Watching the same gun camera footage, he noticed the angles of the bullets and how they dispersed long before reaching the target. He understood it was not bad piloting—it was poor geometry. McCarthy studied the technical manuals and realized the outboard guns’ angles left bullets too spread out. A closer convergence could dramatically improve accuracy.

He calculated a new convergence point at 300 feet. At this range, the target moved only a short distance before the bullets arrived. Shorter distance meant tighter grouping and far higher probability of hitting the enemy. McCarthy knew the risk: too much inward angle could damage the aircraft. But the cost of doing nothing was higher, as pilots continued to die while firing useless rounds.

The Night Adjustment

In the early hours, McCarthy and two fellow ordinance men quietly adjusted Captain Sweat’s Corsair. They reinforced the gun mounts with steel plates and set each Browning gun to converge at 300 feet. At dawn, test bursts destroyed a target frame, forming a solid column of tracers. Sweat, initially skeptical, realized the modification worked. When his squadron engaged Japanese fighters later that morning, the results were immediate. Multiple enemy aircraft were destroyed in seconds with ammunition to spare.

Within days, word spread. Other squadrons requested the modification. By October 1943, nearly every Marine Corsair in the Pacific used the 300-foot convergence. Kill ratios soared, ammunition efficiency improved, and pilots regained confidence. Reports of engagements show pilots shooting down multiple aircraft while still carrying half their ammunition.

Legacy of the Modification

The success of McCarthy’s adjustment eventually led to official adoption by the Bureau of Aeronautics. Structural tests later revealed his crude reinforcements actually strengthened the wing mounts. Yet McCarthy’s name never appeared in manuals or reports. Pilots, however, remembered. In squadron gatherings, the story of the sergeant who defied orders and rewrote the rules of aerial combat was told repeatedly.

From September to December 1943, Marine Corsairs achieved an 11-to-1 kill ratio over the Solomons, a dramatic improvement from weeks prior. The modification did not just enhance firepower—it saved lives. The careful observation, calculation, and courage of one mechanic transformed a struggling fighter into a dominant weapon in the Pacific, proving that sometimes innovation comes not from officers or engineers, but from someone willing to see what others overlook.