How One Ingenious Mechanic Built a “Bamboo Fleet” to Save U.S. Aircraft in the Pacific

Philippine Air Force, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

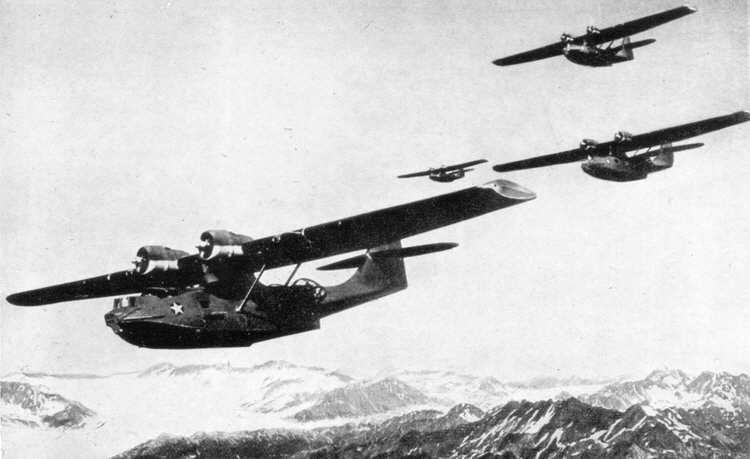

August 8th, 1942, Iron Bottom Sound, south of Guadalcanal. The night carried the smell of cordite and salt. Engines hummed, and the echoes of artillery rolled in from the jungle. A PBY Catalina limped over the dark Pacific, its left float shredded and fuel leaking. Inside, aviation machinist’s mate Charles M. Mallister gripped the throttle as the right engine coughed and sputtered. His co-pilot warned that the pressure was dropping again. The damaged plane struggled to stay level as waves struck its belly. By the time it reached Tulagi, the aircraft was half submerged, patched with rivets and whatever materials were on hand. Mallister didn’t speak. He simply stared at the bullet-pocked hull, thinking.

The next morning, under the harsh sunlight at Henderson Field, the crews of Naval Construction Battalion 6 faced a critical shortage. Their supply ship had been sunk two days earlier, taking the last crates of steel plating with it. Every Catalina returning from patrol carried holes large enough to fit a fist. Commander Edward “Pops” Lane ordered his men to scavenge everything possible: ship debris, engine covers, even tin cans. Mallister, however, saw another possibility. Just beyond the wreckage, tall bamboo stalks swayed in the wind. Light, hollow, and resilient, they sparked a memory from before the war: a Filipino craftsman had shown him that layered bamboo soaked in resin could resist cutting. Could it serve as armor?

Innovation in the Jungle

At first, the idea drew laughter. “Bamboo armor?” a fellow mechanic scoffed. Mallister ignored it. That evening, he boiled resin from aircraft sealant, cut bamboo into sheets, and layered them crosswise. Using sandbags and flattened tent doors, he pressed the layers together. Three days later, they mounted a panel on a test frame and fired captured Japanese Type 92 rounds. The first shot cracked the top layer; the fifth round barely dented it. Mallister noted that three layers would suffice. Word spread quickly. Soon, these bamboo panels were replacing shredded steel on returning Catalinas. The repairs were lighter, saving nearly 100 pounds per plane, and surprisingly effective.

The first mission with bamboo-plated aircraft flew on August 17th, 1942. Patrol Squadron 23’s PBY 44, call sign Black Cat, faced enemy fire over the Solomon Sea. A strafing run by a Japanese Zero hit the plane, but one bullet only partially penetrated the bamboo laminate. The pilot later reported that he could feel the strike bounce off. Mallister remained quiet, simply lighting a cigarette and staring into the jungle. By September, the bamboo panels were proving their value. Henderson Field, a cratered strip of dust and wreckage, was under nightly bombardment. Yet planes with bamboo reinforcements consistently returned, their hulls holding where steel had failed.

Battle-Tested and Field-Proven

In the cramped repair bays, Mallister moved among the crews, inspecting, adjusting, and teaching. Petty Officer Harris tested new panels repeatedly. Properly cured resin allowed the bamboo to flex rather than break, unlike brittle steel. During a night raid by Japanese bombers, Mallister and Harris took off in one of the newly armored PBYs. Explosions rocked the plane, yet the bamboo panels absorbed six direct hits without breaching the crew compartment. Hours later, they landed safely, confirming that the jungle-grown material could indeed save lives.

News of the bamboo-plated aircraft reached other Pacific bases, from Espiritu Santo to Noumea. Crews experimented with the panels, reporting that they were light, buoyant, and effective in combat. Bureaucratic orders dismissed the innovation as “non-standard,” but Mallister ignored them. Every battered Catalina that returned alive validated his work. Through the end of 1942, Mallister quietly coordinated repairs, teaching younger men how to maintain the makeshift armor. Photographs captured the distinctive cross-hatch pattern, though the images were lost in transit. The bamboo fleet continued to protect pilots and crews, even as steel and aluminum slowly returned to supply lines.

By early 1943, Mallister rotated home, recognized for excellent conduct but without official acknowledgment of his innovation. In Oregon, he returned to civilian life, often telling neighbors simply, “We built planes out of trees. Work just fine.” Decades later, veterans recalled the bamboo panels as crucial to survival. Declassified records confirmed that during six months of use, no bamboo-armored Catalina was lost to small-caliber fire. Mallister died in 1974, largely unrecognized, yet his ingenuity remained alive in the history of the Pacific Fleet. His story demonstrates how creativity, resourcefulness, and courage can protect lives even in the most desperate circumstances.