How a Mechanic’s “Illegal” Tweak Turned the Mosquito Bombers into the Fastest Plane of WWII

Britain At War / YouTube

The RAF’s Wooden Wonder

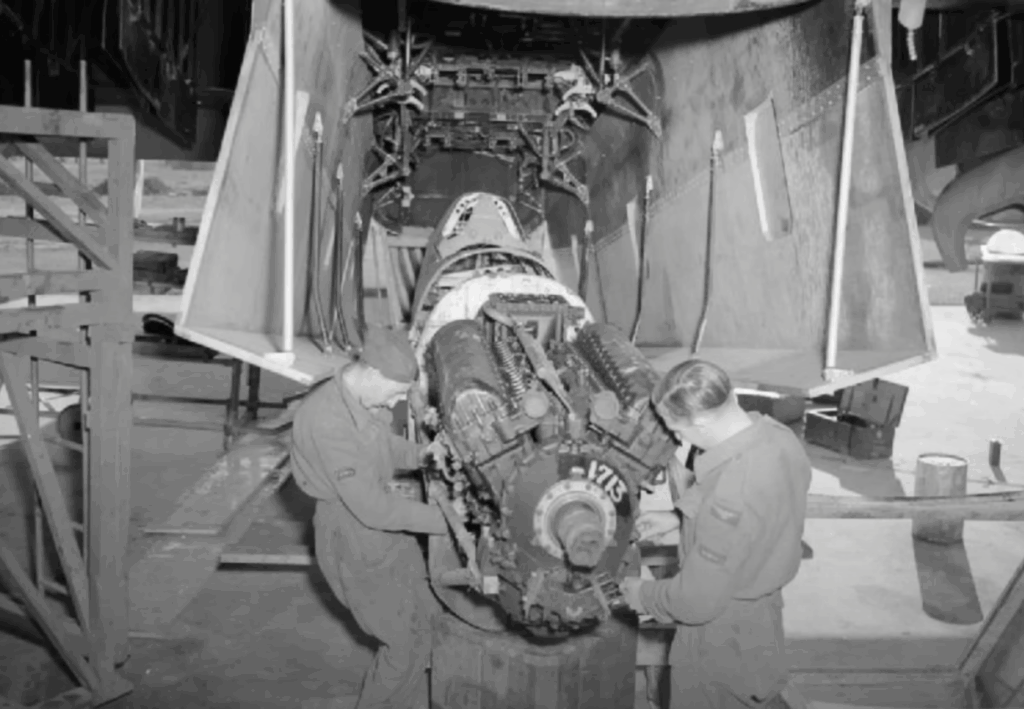

In the early 1940s, the Royal Air Force introduced one of the most remarkable aircraft of the Second World War—the de Havilland Mosquito. Built largely from wood when metal was scarce, it was light, versatile, and faster than most single-seat fighters of its day. Its combination of speed and precision made it suitable for reconnaissance, bombing, and even night fighting. Yet behind its incredible performance was an unassuming engineer whose name rarely appeared in official records—Roderick “Rod” Banks.

Banks was an RAF ground engineer stationed at several maintenance units, including RAF Marham. Known for his deep understanding of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, he had a habit of questioning orders and testing limits. When pilots complained that their Mosquitoes were being caught by German Fw 190 and Bf 109 fighters during deep raids over occupied Europe, Banks believed the problem lay not in the aircraft’s design, but in the strict engine settings imposed by the Air Ministry.

An Unauthorized Experiment

The Mosquito’s twin Merlin engines were designed to handle high boost pressures, but operational settings were deliberately restricted to preserve engine life. Banks, convinced that the aircraft could safely produce more power, began experimenting after hours. He carefully adjusted the boost control system—essentially increasing the amount of air and fuel mixture forced into the cylinders. These small, unauthorized changes gave the engines a temporary surge in power far beyond official limits.

It was an “illegal” modification, one that could have ended his career if discovered. But Banks tested his adjustments under controlled conditions and monitored fuel flow, temperature, and detonation risk. The results were astonishing. The Mosquito gained an estimated 25 to 30 extra miles per hour, enough to outpace the fastest German interceptors at low and medium altitudes. Pilots soon noticed that aircraft tuned in Banks’s workshop were consistently faster and could climb more aggressively when chased.

From Workshop Secret to Wartime Necessity

As word spread, crews began to quietly request that their planes pass through Banks’s maintenance bay before missions. The practice became an open secret within parts of RAF Bomber Command. During raids such as Operation Jericho—the famous 1944 attack on Amiens Prison—Mosquito pilots used that extra burst of speed to escape enemy fighters and heavy ground fire. Records from squadron diaries and pilot testimonies later suggested that aircraft with these modified engines suffered significantly fewer combat losses.

The performance edge was not merely mechanical—it gave crews new confidence. Knowing that their plane could outrun danger, Mosquito pilots often flew deeper into occupied territory for precision strikes that larger bombers could not attempt. Banks’s “tuned” engines became a quiet force multiplier, achieved not through new technology, but through human initiative.

Changing the RAF’s Thinking

Eventually, the improved performance of certain Mosquito squadrons reached senior officers, and engineers from Rolls-Royce were dispatched to investigate. Instead of punishing Banks, they studied his method. His empirical adjustments provided data that led to authorized revisions of boost pressure and fuel control systems in later Merlin variants. The Mosquito’s already legendary speed—sometimes exceeding 400 miles per hour—became officially achievable across the fleet.

Banks’s wartime contributions were later recognized informally by his peers, though official credit was limited by the secrecy surrounding unauthorized modifications. He continued to work in aviation after the war, applying the same practical ingenuity that had once bent the rules to save lives.

Legacy of Ingenuity

The story of Roderick Banks illustrates how innovation often comes from the ground up. In a war driven by mass production and bureaucracy, one mechanic’s willingness to trust his judgment helped transform an already remarkable aircraft into something extraordinary. The Mosquito’s reputation as “the wooden wonder” owed as much to quiet acts of engineering courage as to official design. And in the hangars of RAF Marham, a sergeant’s “illegal” tweak helped make it the fastest operational aircraft of the Second World War.