The Most Dangerous Job an Airman Could Have in World War II

Photo by Royal Air Force official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Into the Frozen Sky

Flying a bomber in World War II was one of the most dangerous jobs a soldier could face. At altitudes of 20,000 to 30,000 feet, crews faced an environment that was almost as deadly as enemy fire itself. The skies were thin, cold, and merciless. Airmen, often between 19 and 25 years old, were tasked with navigating massive aircraft over hostile territory, carrying tons of explosives while exposed to the elements. Without pressurized cabins, survival at these heights relied on heavy clothing and electrically heated suits, known as F1 Blue Bunnies. These suits used coiled wires to generate warmth, keeping men from freezing, but a failure in the system could leave them soaked in sweat one moment and chilled to the bone the next.

Oxygen was another constant struggle. At altitudes comparable to the summit of Mount Everest, hypoxia could strike quickly, causing confusion, loss of coordination, and even unconsciousness. Oxygen masks and tanks were necessary, but they were far from perfect. Moisture from breath could freeze in the tubes and valves, reducing the oxygen supply without warning. Even basic human needs became dangerous: urine could freeze in clothing or boots, forcing airmen to improvise in the harsh environment. These conditions made every mission a fight for survival before the enemy even came into view.

Machines of War

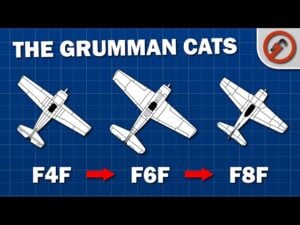

The Eighth Air Force relied primarily on two types of bombers: the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator. The B-17 earned its nickname for its metallic construction and the dozens of machine guns mounted to defend against enemy fighters. It carried up to ten .50 caliber guns, including two in a Sperry ball turret beneath the fuselage. Operating this turret was a challenge. Gunners had to lie in a cramped, hunched position, their knees bent above their heads, while the machine guns recoiled within inches of their face. The experience was uncomfortable and often dangerous, but it was essential for survival against German interceptors.

The B-24 Liberator offered improvements in bomb capacity, speed, and crew safety. Its retractable ball turret reduced the risk for gunners, and the aircraft could carry heavier loads over long distances. Both bombers were equipped with the Norden bomb site, a mechanical computer that calculated bomb release based on altitude, speed, and direction. In theory, it could drop bombs within a 75-foot radius of a target. In practice, vibration, wind, and equipment failures often reduced accuracy, making repeated missions over the same target necessary. Cities like Bremen, with critical shipyards and factories, could be hit more than a dozen times, with crews flying into the same deadly skies again and again.

Death from the Sky

Despite their defenses, bombers were vulnerable. German fighters, like the Bf 109, and anti-aircraft artillery remained deadly threats. High-altitude flights avoided smaller guns, but larger, high-velocity cannons could tear through aircraft skin as thin as a soda can. Bullets and shrapnel could easily penetrate fuel lines, control cables, and even the crew compartment, causing severe injuries or death. Crews quickly learned to rely on flak jackets and steel helmets, but protection could only do so much. Flying in tight formations was a tactical necessity. Bombers relied on overlapping fields of fire to defend against attackers, but maintaining these formations required precise coordination. Any misstep could lead to collisions or leave a bomber exposed.

Survival also depended on a crew’s ability to bail out if the aircraft was fatally damaged. Unlike modern planes with ejection seats, World War II bombers required men to climb through hatches or the bomb bay, often while the aircraft spun uncontrollably. High G-forces could pin them against the fuselage, and the fall to the ground was another trial. Descending for two and a half minutes, airmen faced flak, enemy fighters, and debris. Reaching the ground did not guarantee safety. Many were captured and sent to prisoner-of-war camps, while others were killed by local defenders or had to find friendly resistance forces. Every step, from takeoff to landing, involved facing the constant risk of death.

Missions of Madness

Once over the target, the bombardier had to operate the Norden bomb site under extreme stress. Mechanical failures and minor errors could send bombs off course. The standard 250-pound bomb was often insufficient to destroy heavily fortified targets, forcing repeated missions and exposing crews to even greater danger. Returning to England meant facing the gauntlet again: flak, fighters, and damaged engines. In emergencies, excess weight could be jettisoned, including ammunition, machine guns, and even the Norden bomb site, to improve the aircraft’s chances of reaching home. Landings could be challenging if the hydraulic system failed, but many bombers could still perform wheels-up landings. The ball turret was often removed to prevent additional damage on touchdown.

Medical and maintenance crews were a vital part of this cycle. Severely wounded airmen were prioritized for treatment, while those still capable were rushed back into service. The 25th mission became a milestone, a psychological goal for crews hoping to survive a full tour. By 1944, the minimum number of missions rose to 30, a threshold few reached without being killed, wounded, or captured. The Eighth Air Force suffered staggering losses, with 47,000 men dead, wounded, or missing. Yet even in the face of such odds, crews returned to the air repeatedly.

Courage and Tenacity

Stories of bravery were common. Staff Sergeant Shorty Gordon, a ball turret gunner, flew every mission despite frozen extremities and failed heated suits. He repaired weapons at extreme altitudes while enemy fighters attacked, ensuring the plane’s defenses remained operational. Similarly, John Curico, navigating a severely damaged B-24, chose the risky path of returning to base rather than landing in neutral territory, keeping the aircraft and crew intact.

These men faced conditions most people cannot imagine: bitter cold, low oxygen, enemy fire, and the constant threat of death. Yet they endured, exemplifying determination and skill under pressure. Every mission was a test of physical endurance, mental strength, and teamwork. The bomber crews of World War II were not just operators of machines; they were men confronting the limits of human survival in one of the deadliest theaters of the war.