The First P-47 Ace Who Helped A Japanese Pilot

Yarnhub / YouTube

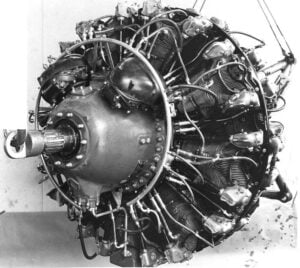

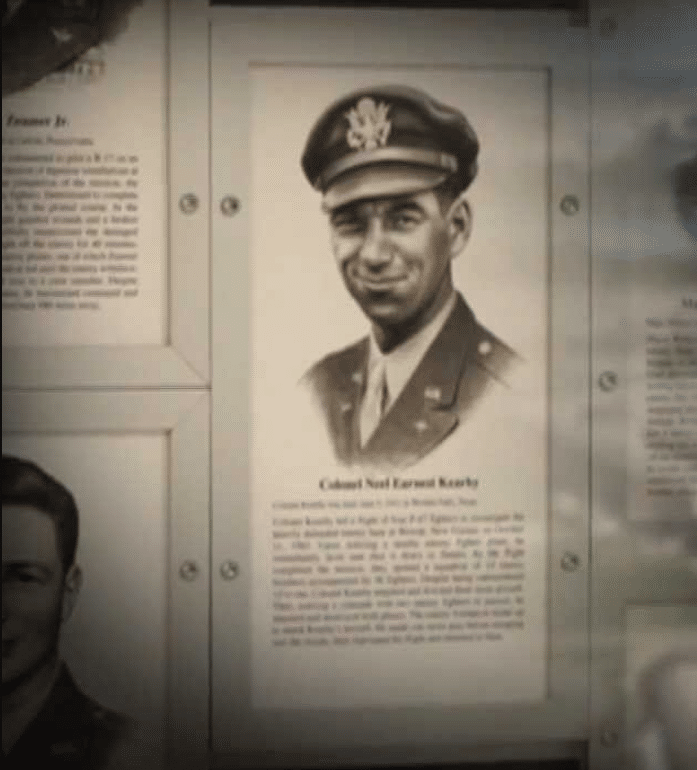

In March 1944, the Pacific War reached a critical point as American fighter pilots competed to break World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker’s record of 26 victories. Among them was Neel Kearby, a highly skilled pilot with 21 confirmed victories. Flying his P-47 Thunderbolt, known as “Fiery Ginger Four,” Kearby had two goals in mind: surpass Rickenbacker’s record and demonstrate the capabilities of the Thunderbolt in combat. Despite criticisms that the Thunderbolt was inferior to Japanese planes in agility, Kearby used its strengths—especially its powerful dive and eight .50 caliber machine guns—to prove its effectiveness.

Kearby was passionate about the P-47 Thunderbolt. As newer models like the P-38 and P-51 began to replace the Thunderbolt, Kearby wanted to ensure it continued to play a key role in the war. He believed that if he could break the standing record in his Thunderbolt, it would attract media attention and secure its place in the conflict. With that in mind, he set out on a fighter sweep with fellow pilots Bill Dunham and Sam Blair, unknowingly heading toward a fateful encounter.

A High-Stakes Mission

Flying at 22,000 feet over the coast of Papua New Guinea, Kearby and his squadron first encountered a Kawasaki Ki-61, but decided to pass it by. Their goal was to find more valuable targets. Shortly after, they spotted three Ki-48 bombers. Using the Thunderbolt’s “boom and zoom” strategy—diving at high speed to attack and then climbing back up—the trio engaged the enemy. Dunham and Blair quickly took out two of the bombers, but Kearby pursued the third. In his eagerness to finish off the target, he made a critical mistake.

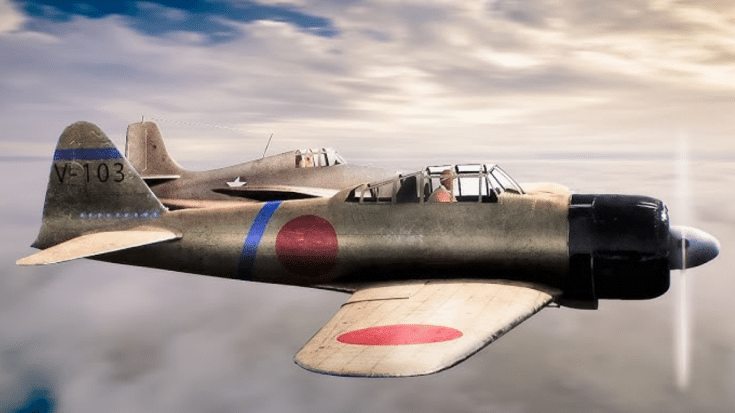

Kearby slowed down and circled back, losing the advantage of speed and altitude that his Thunderbolt relied on. This left him vulnerable to attack, and a Ki-43 Oscar seized the opportunity. The Japanese fighter severely damaged Kearby’s plane. Dunham, seeing Kearby in trouble, rushed to his aid and managed to take down the attacking Oscar, but Kearby’s P-47 had already been mortally wounded.

Dunham and Blair searched desperately for Kearby over land and sea, but as their fuel ran low, they were forced to return to base. Dunham, determined to find his friend, attempted to launch a second search, but the darkness and the exhaustion of his comrades prevented him. Kearby was lost.

A Moment of Mercy

Months after Kearby’s death, Bill Dunham faced a moment that would define his military career. While flying over the Philippine Sea in his P-47D, he engaged and shot down a Japanese Ki-43 Oscar. As the enemy plane spiraled toward the ocean, Dunham saw the pilot eject and float down beneath his parachute.

At that moment, Dunham found himself wrestling with a difficult choice. It was not uncommon for pilots on both sides to target enemy aviators even after they had bailed out. The harsh reality of war often pushed soldiers to continue fighting, even when their opponent was defenseless. Dunham had the pilot in his sights and could have easily followed this grim tradition. Yet something stopped him.

Dunham later described feeling as though a higher power intervened in that moment, guiding him away from the usual violence of war. Instead of firing on the vulnerable Japanese pilot, Dunham made an unexpected decision. He maneuvered his Thunderbolt close to the enemy pilot, opened his canopy, and dropped his life jacket—known as a “Mae West”—to the Japanese aviator drifting in the ocean below. In a gesture that transcended the conflict, Dunham chose mercy over combat.

Uncommon Chivalry

Dunham’s act of compassion was remarkable in the brutal context of WWII. This moment was later immortalized in a painting titled “Uncommon Chivalry,” which is displayed at the Seattle Museum of Flight. The image serves as a reminder that even in war, moments of humanity and kindness can shine through. Dunham risked his own safety to save the life of an enemy pilot, and this decision set him apart from many of his peers.

The Legacy of Neel Kearby

Although Kearby’s final mission ended in tragedy, his legacy did not end over the skies of Papua New Guinea. In 1948, four years after his disappearance, an Australian search team found Kearby’s remains deep in the jungle. Evidence showed that he had survived the crash but died from his injuries before he could be rescued. In the 1990s, parts of his P-47 Thunderbolt were recovered from the crash site, and these fragments were later used to create a replica of his aircraft at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.