German Pilots Laughed at the P-47 Thunderbolt, Then Learned to Fear Its Eight .50 Calibers

The Second World War Tales / YouTube

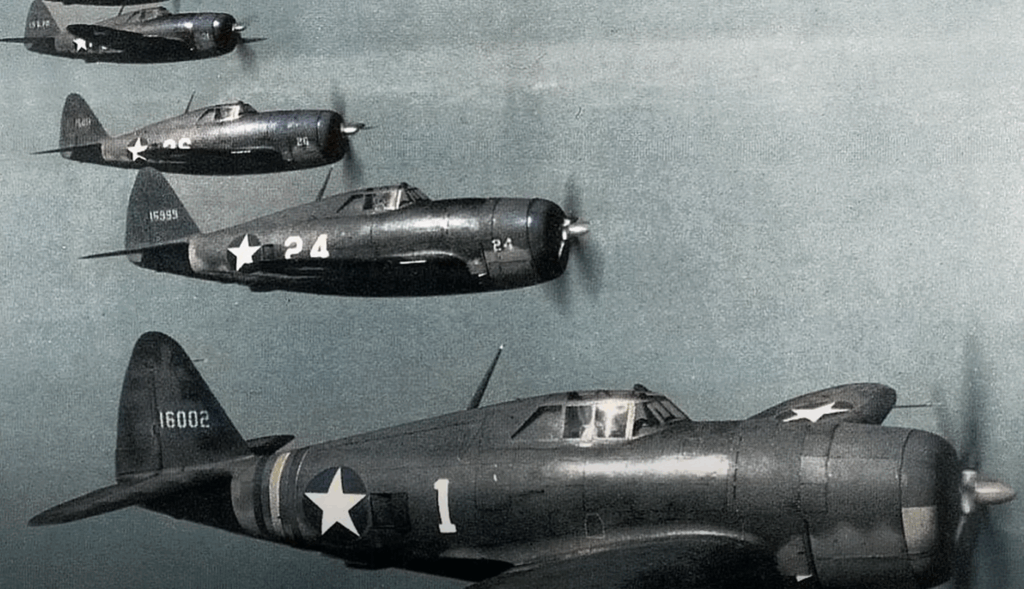

On that April morning in 1943, German pilots looked up to see what they believed to be a comic mistake in the skies. They expected nimble, sharp fighters—but instead they saw bulky machines that defied their expectations. Within months, those machines would change how air war was fought, turning mockery into terror.

Mockery Over Belgium

April 15, 1943. At 25,000 feet over occupied Belgium, Captain Werner Schroer of Fighter Wing 26 saw the American fighters approaching his formation and could barely believe his eyes. He radioed, “The Americans are flying barrels.” Compared to the sleek German fighters he flew—fast, agile, lean—these Republic P-47 Thunderbolts looked absurd. Their big round engines, bubble cockpits perched on thick fuselages, and short wings made them seem more like flying cargo boxes than combat aircraft.

German pilots, experienced and confident, had no respect for these newcomers. They flew agile “Falke”-type fighters, which dominated the skies with quick turns and speed. These Americans, hardly battle-hardened, seemed ill-fitted for combat. What threat could these bulky planes pose?

The Iron Inside the Jug

But beneath the awkward shape lay a surprise. The P-47 was designed not for elegance but for strength. Weighing about 10,000 pounds empty—heavier than some twin-engine aircraft—and powered by a 2,000+ horsepower Pratt & Whitney engine, it could reach high altitudes where German engines struggled. It could not match the Germans in turn rate or low-altitude climb, but in other ways it was unmatched.

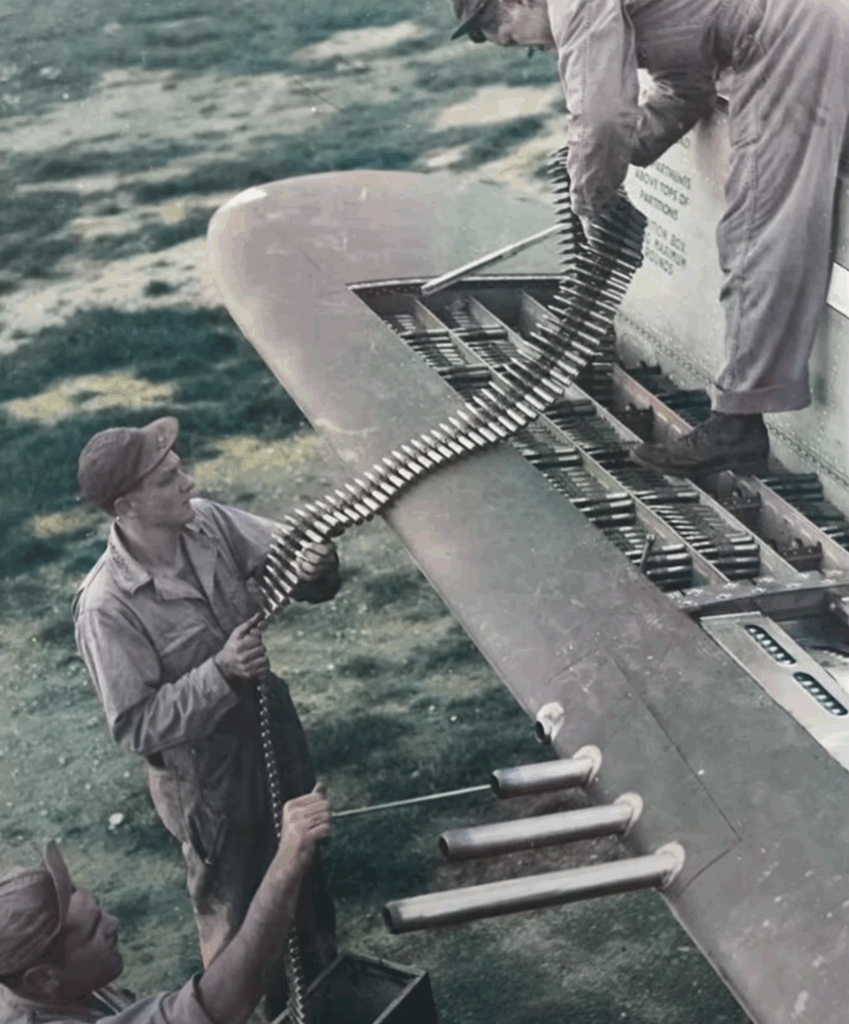

The true power lay in its armament. The P-47 carried eight Browning .50 caliber machine guns, each loaded with 425 rounds—totaling 3,400 rounds. Those eight guns firing together could spray 100 bullets per second into a target zone about six feet wide. American engineers refined their placement through tests—shooting giant paper targets over enemy lines at night, sending spies to observe bullet clusters, and tuning the timing so that all bullets converged at about 300 yards into a small lethal zone.

A Pilot Who Proved the Power

On June 26, 1943, Lieutenant Robert Johnson discovered the Jug’s real power. German fighters attacked him, riddling his aircraft with over 200 hits. His hydraulic controls failed, his canopy jammed, and his fuselage was pockmarked. Yet his P-47 kept flying. After the attack, a German pilot reportedly saluted Johnson’s battered plane and flew off in disbelief. No German fighter could have survived such punishment. Word of Johnson’s ordeal rippled through German squadrons.

By autumn 1943, American pilots learned what tactics would be winning with the Thunderbolt. They avoided turning fights at low altitude and instead climbed to 30,000 feet where their turbocharged engine gave them supremacy. From that height, they would dive at over 500 mph, outrunning opponents even later in the war when jet fighters appeared. Pilots had to use special throttle techniques lest the propeller tips break the sound barrier and shatter the blades under stress.

Turning the Tables

Captain Francis Gabreski, a top ace, said when the P-47’s guns hit a target, the enemy did more than fall: they disintegrated. One German pilot was said to have been cut in half before he knew what struck him. A two-second burst from all eight guns launched 200 bullets at 300 yards—creating a wall of lead no aircraft could survive. These bullets used armor-piercing incendiary designs, burning at 3,000°—enough to melt aluminum instantly.

Among Germans, one ace named Hans Phillip met his end on October 8, 1943. His engines choked at high altitude while P-47s, in their element, dove on his formation. Johnson’s combat report was brief: “Saw hits along the body. Aircraft exploded. No parachute.”

The psychological effect was immense. If Phillip, who had flown 500 missions, couldn’t survive, what hope did average German pilots have? Adding to the fear was the P-47’s water-injection “war emergency” system, which gave a burst of 800 extra horsepower. Later, in January 1944, a paddle-blade propeller upgrade raised climb rate by 40%, allowing the P-47 to contest even German fighters on that metric.

From Mockery to Fear

Early P-47s earned the nickname “Razorback” by Germans due to their angular top canopy, and others called them “Jugs” for their heavy shape. At first, German pilots derided them. By 1945, many admitted regret. Major Joseph Priller, once mocking the type, later said the Thunderbolt was “the perfect fighter-bomber.” He noted its guns never jammed, never overheated, and it outmatched expectations. He said, “We laughed at them in 1943. Nobody laughs now.”

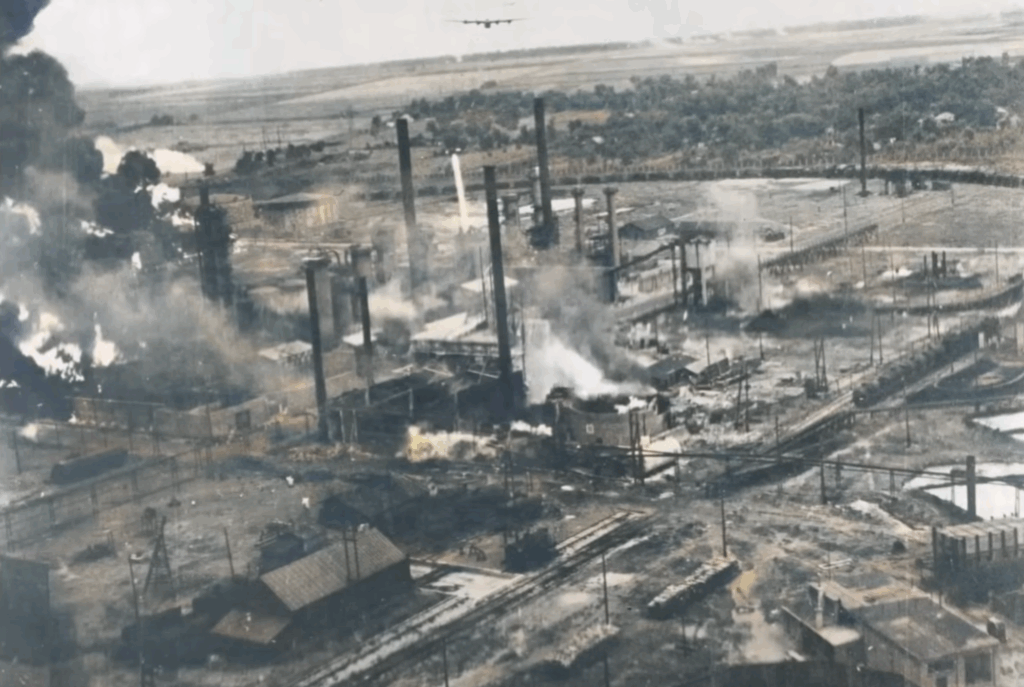

In total, P-47s destroyed thousands of German aircraft—many in air combat and even more on the ground during ground-attack missions. Their kill ratio often exceeded 4:1. Many pilots preferred to belly land damaged Jugs rather than bail out because the airframe often held together when other fighters would break apart. Some ran engines missing cylinders or with control systems destroyed, and still landed safely.

Pilots praised its roomy cockpit; tall flyers who could not fit into other fighters found comfort in the P-47. One joked you could walk inside it during long missions—a stretch, but the extra space mattered.

After the war, German commanders admitted they had misjudged it. They built elegant fighters, but the Americans built something different: mass-produced, heavily armed, built for survival. They produced 15,683 P-47s, more than any other U.S. fighter. That scale, combined with raw firepower, overwhelmed German skies. By 1943, the laughter had stopped. The skies belonged to the Jug.