The Secret Upgrade That Made the P-47 Thunderbolt a Deadly Force

WWII Time Machine / YouTube

A Heavy Fighter With a Weakness

In the skies above northern France in early 1944, German pilots believed they understood the American P-47 Thunderbolt. The fighter was known for its toughness, its ability to dive at great speed, and its capacity to withstand heavy punishment. Yet it also had a flaw—its slow climb rate. German tactics were built around this limitation. They would strike from above, make a fast pass, and then pull away vertically, confident that the heavier Thunderbolt could not follow.

This method worked for months and became a fixed expectation. German pilots trusted that if they gained height, the Thunderbolt would fall behind. That sense of certainty ended suddenly when formations of Thunderbolts began climbing after them in ways that defied previous experience. Something had changed inside the American fighter.

The Turning Point in the Air

The first encounters with upgraded Thunderbolts were unsettling. German leaders ordered their usual escape maneuvers, only to hear the deeper, harsher roar of a P-47 that kept pace instead of stalling. The American fighter, once mocked as a heavy brute, now rose meter for meter, breaking rules pilots had come to rely on. For seasoned aces who lived by instinct, the shock was immediate.

What seemed like magic in the air was the result of steady engineering work on the ground. American designers and mechanics had been searching for ways to remove the Thunderbolt’s single major flaw. Their solution came through two linked innovations: a chemical cooling system and new propellers that gave the massive radial engine more effective thrust.

The Power of Water-Methanol Injection

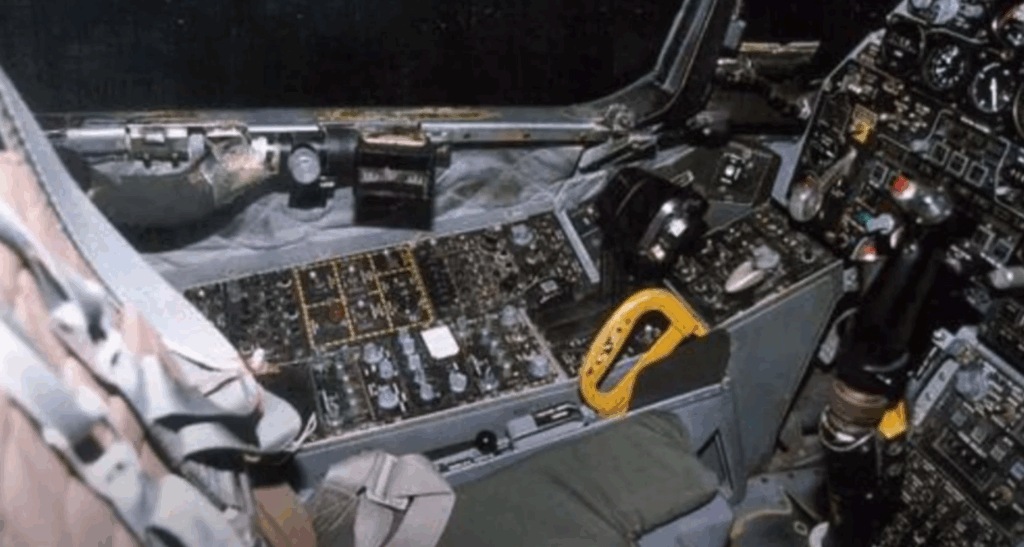

The first upgrade was a water-methanol injection system known as ADI. It sprayed a mixture of water and alcohol into the engine’s supercharger stream. The water cooled the intake temperature, while the methanol acted like an octane booster and contributed additional energy. This combination reduced the risk of detonation, which normally limited engine output under extreme pressure.

With ADI engaged, the P-47’s Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine could produce nearly 2,800 horsepower, far above its normal rating. This surge, called “war emergency power,” was available for short bursts of about five minutes. It gave Thunderbolt pilots a new reserve of strength when they needed it most—during combat climbs or tight pursuits.

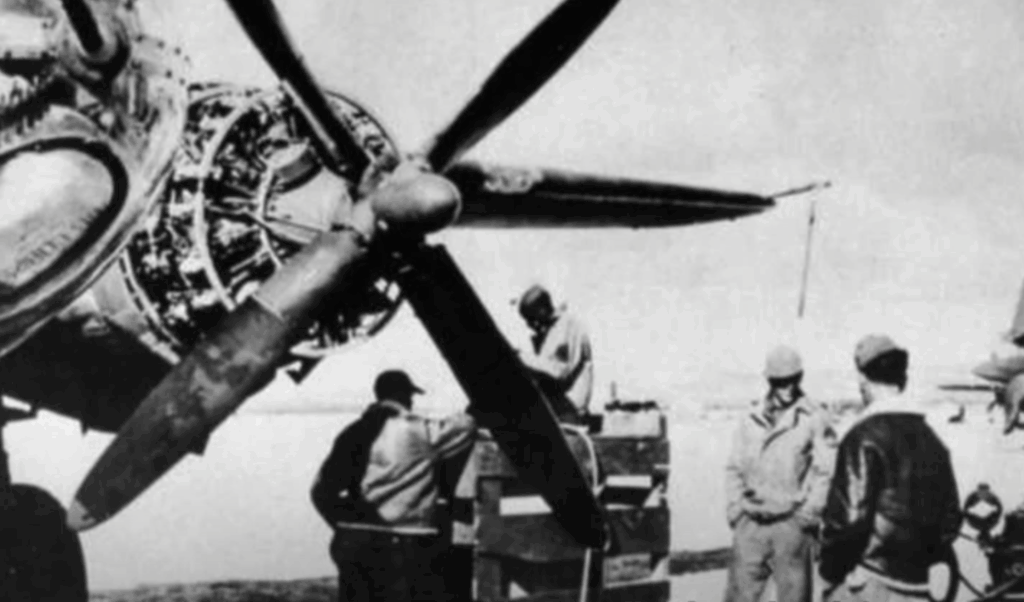

The Propeller That Changed the Climb

The second major change was the installation of Hamilton Standard paddle-blade propellers. Unlike the earlier thin blades, these new propellers had wide, muscular airfoils that gripped the air more effectively. They transformed torque into usable thrust, particularly at lower speeds and in climbs. Even without ADI, the paddle-blade propellers gave the Thunderbolt hundreds of additional feet per minute in climb performance.

Together, the ADI system and the new propellers turned the P-47 into a different machine. It kept its famous ruggedness and diving ability but gained the vertical performance that pilots had long requested. The change was not subtle—it altered the way squadrons fought.

New Tactics in the Skies

Pilots quickly adapted to the upgrades. In combat, they pushed the throttle past a mechanical gate, felt the surge of power, and climbed with confidence they never had before. They learned to save their ADI for the moment when a German fighter tried to spiral upward, closing the gap instead of falling away. Reports spread through airfields in a single phrase: “She goes up now.”

German units soon realized their trusted escape maneuvers no longer guaranteed safety. Interceptors attempting to climb away from bomber escorts found Thunderbolts rising with them, guns ready. The psychological effect was as real as the mechanical one. Once a safe tactic became a trap, and combat planning on both sides had to adjust.

Broader Impact on the Air War

From a technical standpoint, the upgrades made clear sense. The ADI mixture lowered temperatures and raised the detonation ceiling, while the paddle-blade propellers let the engine’s strength turn into rapid climbs instead of wasted heat. For American pilots, this meant freedom to fight vertically as well as horizontally, giving them choices in combat they never had before.

Strategically, the change arrived at a critical time. Escorting bombers across Europe depended on keeping enemy fighters at bay. With the improved Thunderbolt, American formations could hold higher cover, intercept attackers earlier, and disrupt German attempts to mass above the bomber streams. Each month that passed, defenders became fewer and less coordinated.

Challenges and Adjustments

The upgrades were not flawless. The water-methanol mixture had to be handled carefully, and the plumbing needed protection against winter conditions. Pilots also had to discipline themselves not to waste their five-minute burst too early in a fight. But overall, the system was simple to use. A gated throttle and a clear signal gave pilots the power when it counted.

Across hundreds of aircraft, the learning curve was swift. By the spring of 1944, the Thunderbolt had shed its reputation as a sluggish climber. Instead, it stood as a fighter that could choose its terms of combat, a transformation achieved not by redesigning the airframe, but by unlocking the hidden potential of its engine and propeller.