Why P-51’s Weakness in Dogfighting Didn’t Stop It From Helping Win the War

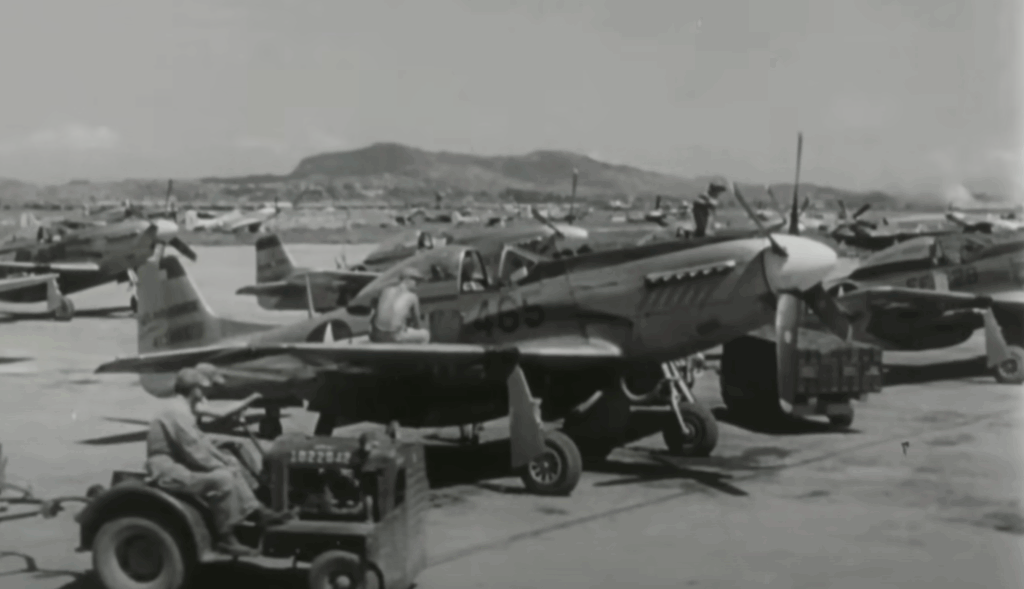

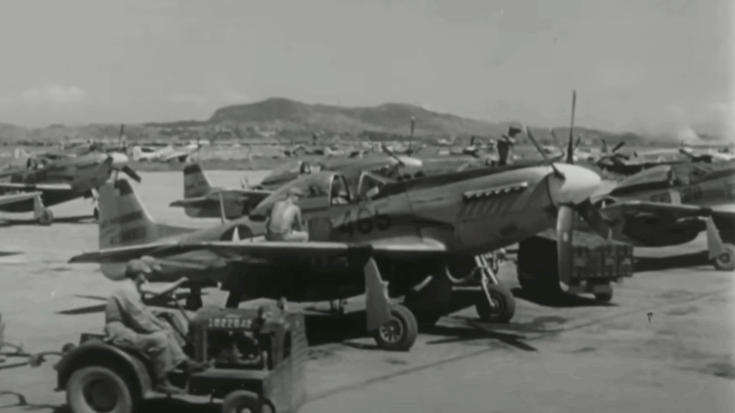

Military History Stories / YouTube

The North American P-51 Mustang is often remembered as the most important fighter plane of the Second World War. Its sleek shape, long range, and deadly record made it the plane that escorted Allied bombers deep into Europe and brought them home safely. Historians and veterans praised its role in turning the tide of the air war. Yet the story of the Mustang is more complicated than its popular image suggests. While it achieved unmatched results as an escort fighter, its weaknesses in classic turning battles meant that it was not always the superior dogfighter it was claimed to be.

Strength in Speed and Range

The Mustang entered combat with impressive statistics. With external fuel tanks, it could fly more than 1,600 kilometers, enough to escort bombers from England to Berlin and back. Its Rolls-Royce Merlin engine pushed the aircraft to speeds over 440 miles per hour at high altitude, climbing to 20,000 feet in under seven minutes. These qualities made it unmatched in reach and endurance. By early 1945, bomber formations flying deep into Germany could rely on cover the entire way, a protection earlier fighters could not provide.

Even German commanders admitted the Mustang was a serious threat. It was fast enough to disrupt interceptions and had the endurance to stay over targets long after other fighters had turned back. By early 1945, daylight raids had become routine, a far cry from the catastrophic losses Allied bombers suffered only two years earlier.

Limits in Dogfighting

Still, pure dogfighting ability did not favor the P-51. Performance in air combat often came down to how tightly an aircraft could turn or how quickly it could climb. The Mustang’s turn rate was slower than that of the British Spitfire Mark IX or the Japanese Zero, and in climb it lagged behind the German Bf 109 and later Spitfire models. Its controls at low speeds were heavier, making sharp maneuvers risky. By comparison, the Spitfire’s wing design allowed smoother handling, while the Zero’s light control surfaces gave it unmatched agility in slow duels.

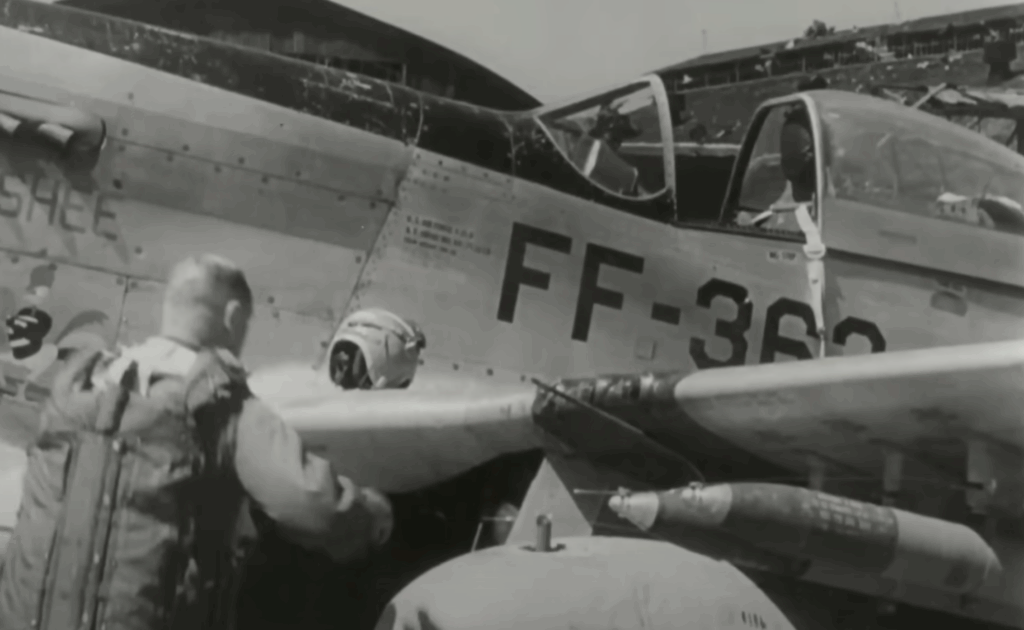

Pilots understood this reality. Ace James Goodson warned that trying to turn against a German Fw 190 at low level could be fatal. Others, such as John C. Meyer and Clarence Anderson, described the Mustang as a thoroughbred that required open skies and speed, not tight circles. Training emphasized hit-and-run tactics: diving from altitude, firing in a swift pass, and climbing away before an opponent could force a turning battle.

The Wing That Helped and Hurt

The key to the Mustang’s strength was also tied to its main weakness. Its laminar flow wing reduced drag and gave it both range and speed, but this same wing stalled abruptly at high angles of attack. In long turns, the Mustang bled speed and risked sudden stalls, while other aircraft gave their pilots more warning before losing lift. German flyers learned to exploit this by luring Mustangs into horizontal turning fights where they held the advantage. Against the Fw 190, which rolled and turned sharply at low altitude, the Mustang was especially at risk once its speed dropped.

The True Role of the Mustang

Yet the Mustang was never designed to be the master of turning battles. Its mission was to keep the bombers alive and wear down German defenses over time. From late 1943 onward, this role became clear. Escorting B-17s and B-24s deep into German territory was dangerous, with fuel, ammunition, and distance working against the pilots. German forces could rearm and refuel at home bases, while Mustang groups had to make every bullet and every gallon of fuel count until they returned to England.

Despite these difficulties, the Mustang reshaped the air war. It not only flew alongside the bombers but also patrolled in front, above, and behind them. Many groups positioned themselves above German airfields, ready to attack fighters as they took off, when they were most vulnerable. By early 1945, German air losses reached unsustainable levels, with Mustang groups often achieving kill ratios of more than ten to one.

Final Impact

In the closing months of the war, hundreds of Mustangs escorted massive raids into German territory. Beyond defending bombers, they strafed airfields, destroyed aircraft on the ground, and left German forces unable to challenge Allied skies. By 1945, the P-51 had helped break organized resistance in the air. It was not the tightest turner or the fastest climber, but it was the fighter that reached the enemy’s heart, stayed there, and ensured that Allied air power remained unchallenged.