How Paddle-Blade Propellers Transformed the Thunderbolt Into a 470-MPH Powerhouse That Germany Feared

The War Files / YouTube

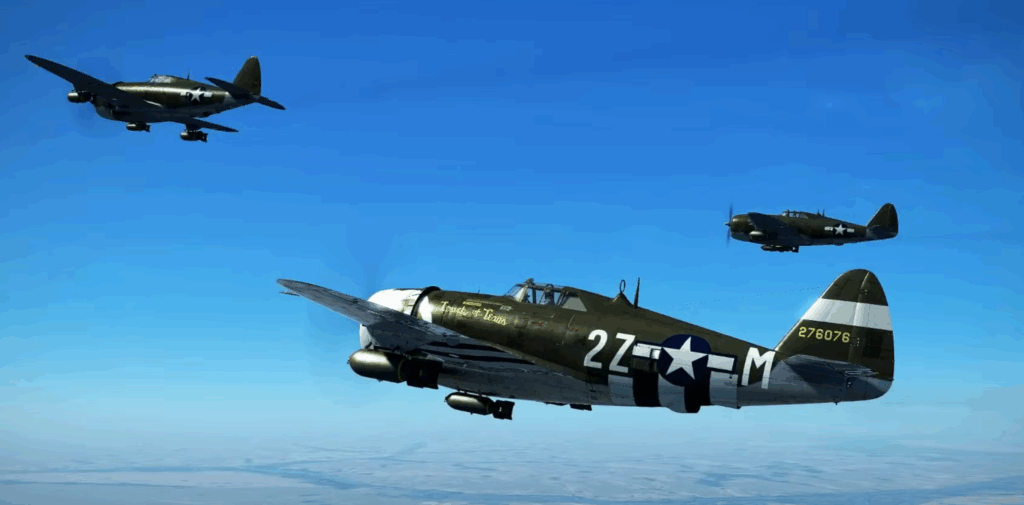

Over Berlin, 1944

On March 6, 1944, high above Berlin, the 56th Fighter Group fought in one of the largest air battles of the war. Silver P-47 Thunderbolts weaved through clouds while German fighters filled the sky around them. For months, the Germans had relied on one reliable escape tactic—climbing steeply until the heavier Thunderbolts could no longer follow. That morning, everything changed.

As German pilots pulled into their familiar vertical climbs, the Thunderbolts stayed with them. Their engines roared, and at near stall speed, they fired. Dark smoke poured from enemy aircraft that had once been untouchable. When the battle ended, the Americans had destroyed eleven planes without losing a single pilot. Confusion swept through the German command. What they did not yet realize was that the Thunderbolt’s success came not from a new engine or weapon, but from an improved propeller design—a simple change that altered the balance of air combat.

The Problem Engineers Faced

A year earlier, in the cold winter of 1943, engineers at Republic Aviation in Long Island studied grim combat reports from Europe. Pilots were losing fights because their planes could not climb fast enough. The Thunderbolt’s powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine produced more than 2,000 horsepower, yet much of that strength was wasted. The problem lay in how the power was turned into thrust.

The early Thunderbolts used narrow-bladed propellers built for speed, not climb. These blades sliced through the air efficiently in level flight, but when pilots pulled up sharply, they lost effectiveness. The engines screamed and overheated, while the aircraft barely gained altitude. Chief designer Alexander Kartveli and his team knew the solution was to create a propeller that could “bite” into the air during climbs without overloading the engine.

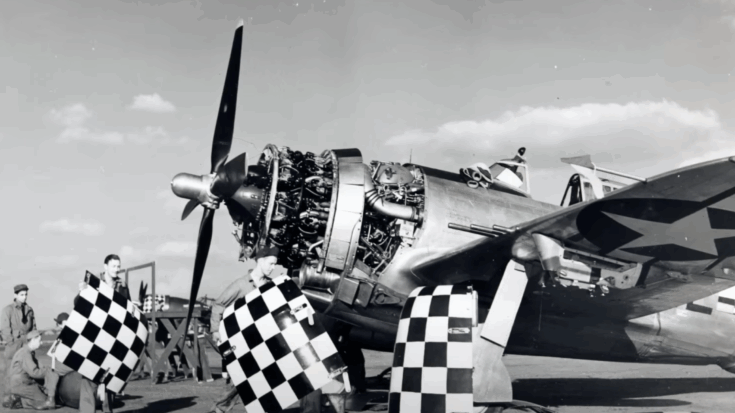

Building a Better Propeller

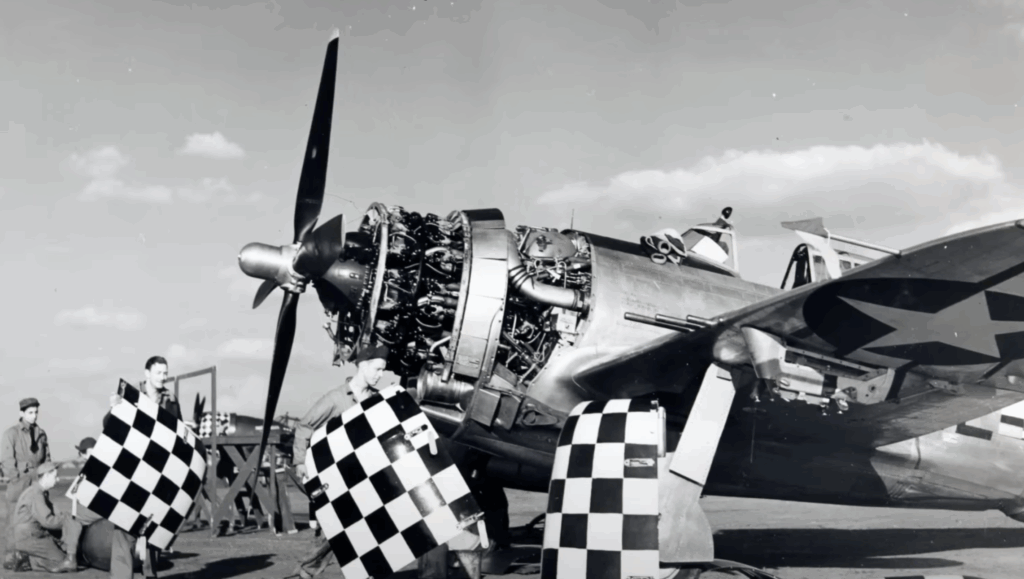

Two major companies were called in to solve the issue—Curtiss-Wright and Hamilton Standard. On paper, the answer looked simple: make the blades wider to grab more air. But in reality, changing blade shape altered the plane’s balance and aerodynamics. Too much drag could rip the propeller or even the engine from its mounts.

All through that winter, engineers tested prototypes, adjusted shapes, and ran wind tunnel experiments. What emerged was far from graceful. The new blades were thick and paddle-shaped, designed to push greater volumes of air. When tested, the results were dramatic. The Hamilton Standard design pulled the Thunderbolt skyward with newfound force, while Curtiss-Wright’s version offered smoother control. Both worked so well that the Army Air Forces decided to approve both designs for production.

A Fighter Reborn

By early 1944, Thunderbolts in England had been fitted with the new paddle-blade props. Colonel Hubert Zemke, commander of the 56th Fighter Group, quickly recognized what it meant. He retrained his pilots to fight vertically—something they had never done before. His new rule was simple: “When a German climbs, follow him up.” That one change in mindset reshaped the air war.

When the upgraded Thunderbolts entered combat, German pilots were shocked. Their old escape move failed. The American fighters could now climb alongside them and strike at the top of the ascent. Gun-camera footage confirmed what many had thought impossible—the P-47s were keeping pace with aircraft they once could never catch. The change had come too quickly for the Germans to adapt. Their engineers, after examining wreckage, believed the larger propellers were meant for better takeoffs, not realizing their true purpose.

Turning the Tide

By February 1944, most Thunderbolt units had switched to the new propellers. During “Big Week,” the massive Allied bombing campaign that targeted aircraft factories, American fighter groups achieved stunning success. German losses soared to more than 350 aircraft, while only 28 Thunderbolts were lost. The improved climb and acceleration allowed pilots to dive, recover, and strike again faster than ever before.

Ace pilots such as Francis “Gabby” Gabreski developed new tactics to exploit the plane’s strengths. Gabreski perfected the climbing spiral, using the P-47’s power to draw German fighters upward until they stalled, then dropping back down to finish them. He later said, “That propeller changed everything. It made the Thunderbolt the airplane we always wanted it to be.”

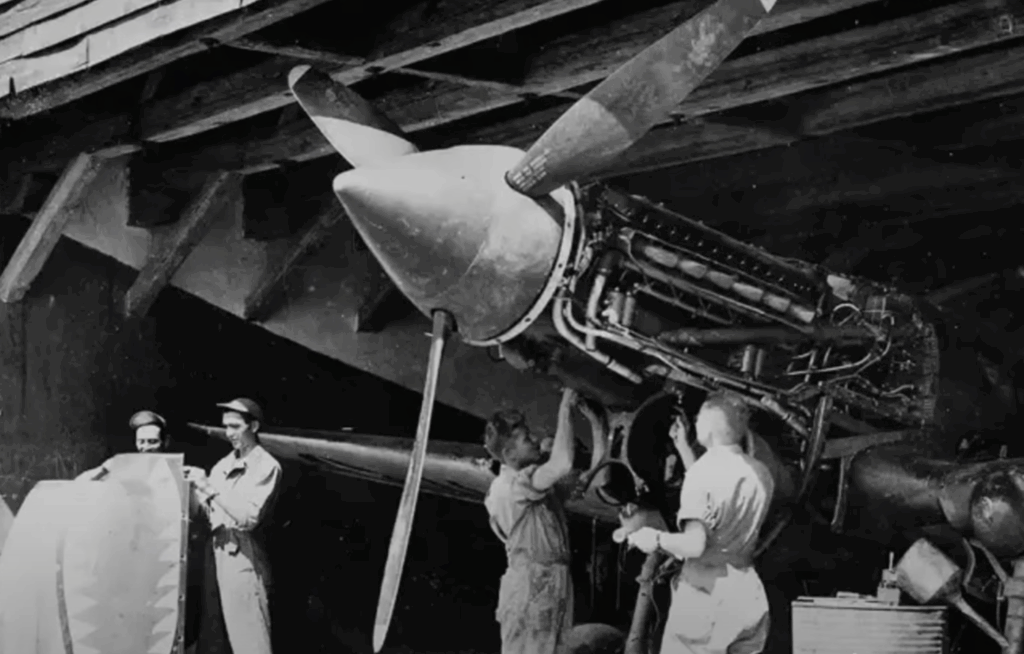

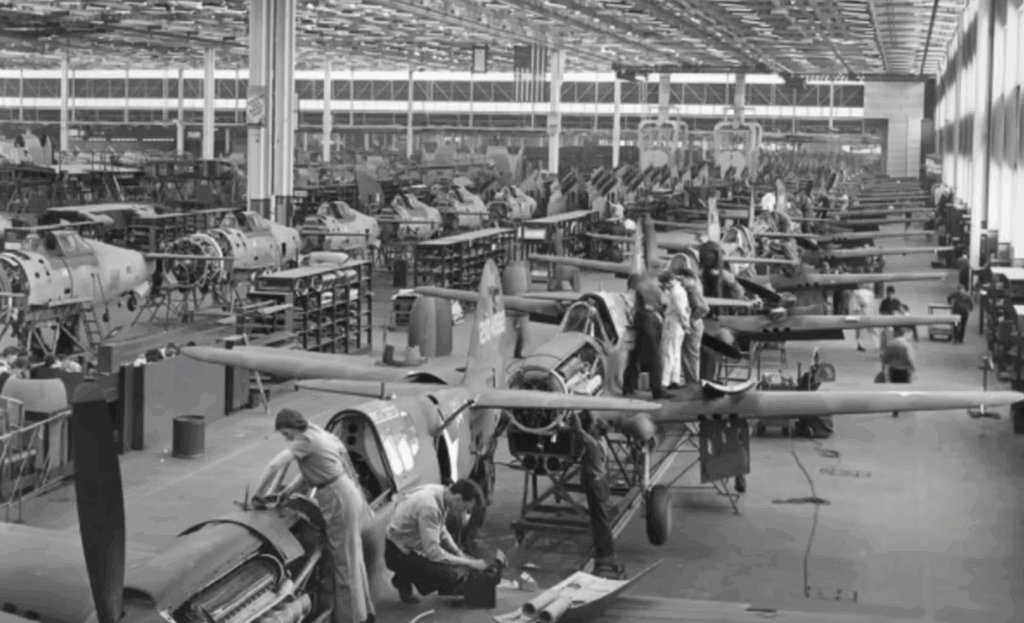

The Wider Impact

Behind every improvement was an enormous industrial effort. Each propeller weighed over 600 pounds and was shipped in heavy wooden crates from American factories to England. Mechanics worked long hours to install them, testing engines through freezing nights. By D-Day in June 1944, more than a thousand Thunderbolts were equipped with the new design. They roared over Normandy’s beaches, destroying armored convoys and defending Allied bombers from above.

Statistically, the results spoke for themselves. Before the change, the Thunderbolt’s kill ratio was less than two to one. Within months, it climbed to over five to one. German pilots began to acknowledge the shift, admitting that the upgraded Thunderbolts could now climb and fight on equal terms.

In less than a year, the P-47 had evolved from a struggling heavyweight to one of the most respected fighters of the war. The secret was not a revolutionary breakthrough, but a practical improvement—a wider, stronger propeller that turned raw power into unmatched performance.