The Pilot Who Defied Orders and Wiped Out a Japanese Fleet in Just 3 Days

Bomberguy / YouTube

A New Way to Fight

In early 1943, the Pacific Ocean had become a vast battlefield where every island and every supply route mattered. The Allied forces were struggling to stop the Japanese convoys that moved men and material between their island strongholds. High-altitude bombing raids, though impressive in scale, were proving useless against moving ships. From thousands of feet above, even a small maneuver by a ship could cause the bombs to miss completely. The hit rate was sometimes as low as one percent. Pilots risked their lives flying through heavy anti-aircraft fire only to see their bombs splash harmlessly into the sea.

Something had to change. That change came from a man named Major Edward “Easy Ed” Liner, a calm but daring officer who saw opportunity where others saw impossibility. Instead of bombing from high above, Liner proposed attacking from just a few hundred feet over the water — low enough that pilots could see the faces of enemy gunners. He believed the ocean itself could become an ally. His idea was to make bombs skip across the surface of the water, like stones thrown across a pond, to strike ships at the waterline where they were most vulnerable.

The Birth of Skip Bombing

The plan sounded reckless. Flying that low meant being a perfect target for ship guns. A single mistake could send the plane tumbling into the sea. Commanders called it a suicide tactic, but Liner believed it could work with the right training and equipment. He teamed up with Paul “Pappy” Gunn, a brilliant self-taught engineer known for his creative approach to combat problems. Gunn took the standard B-25 Mitchell bomber and transformed it into a deadly weapon.

He stripped out unnecessary parts and loaded the nose with as many as eight forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns. These modified bombers, called “commerce destroyers,” were now built to charge directly at ships. The pilots could fire continuously as they approached, suppressing the enemy’s defenses before dropping their bombs. Gunn’s redesign turned the B-25 into something completely new — a fast, heavily armed ship killer.

Forging the Perfect Crew

Liner’s 90th Bombardment Squadron began training near Port Moresby, using a wrecked ship called the SS Pruth as a practice target. Day after day, they flew just 200 feet above the waves, learning to time their bomb drops with precision so that the bombs would skip perfectly into their targets. It was exhausting and dangerous work. The pilots had to master total control — too high, and the bomb would miss; too low, and they could crash. The sound of engines roaring over the ocean became a daily rhythm, as Liner’s men turned theory into muscle memory.

By the end of their training, the squadron had become a finely tuned attack force, capable of hitting targets with deadly accuracy. Each pilot understood the risks. They also understood that success could change the course of the war in the Pacific.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea

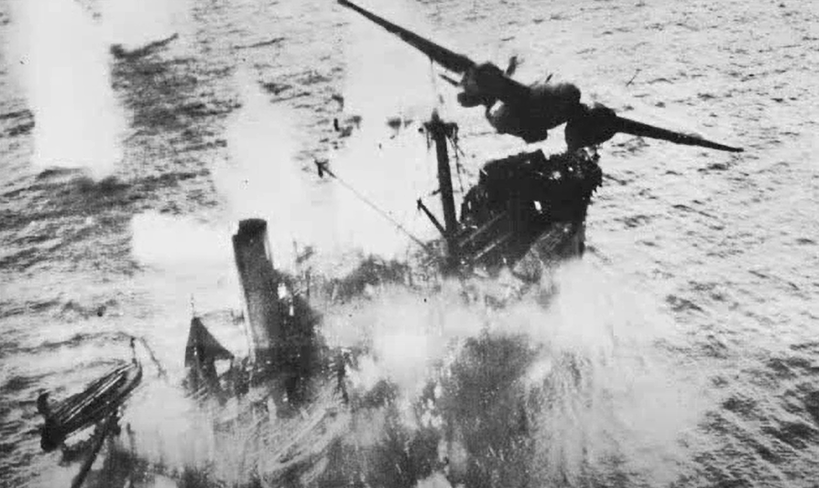

In March 1943, the call came. A massive Japanese convoy was spotted in the Bismarck Sea, carrying thousands of troops and vital supplies to reinforce New Guinea. Liner led the first wave of the attack in his B-25, Pappy’s Folly. As the bombers approached, the sky erupted in black bursts of anti-aircraft fire. Japanese fighters swarmed, but the Americans pressed forward. Flying just above the waves, Liner’s planes roared straight at the enemy ships, their forward guns blazing.

At the perfect moment, the bombs were released — skipping across the water before slamming into the sides of ships. Explosions tore through the convoy. In three days of relentless attacks, all eight Japanese troop transports and four destroyers were sunk. The ocean burned as debris drifted for miles.

A Tactical Revolution

What had been dismissed as a suicidal idea had destroyed an entire fleet. The loss crippled Japan’s supply lines and marked a turning point in the Pacific campaign. Liner’s skip-bombing tactics soon spread across Allied air forces, reshaping how airmen thought about attacking ships. It was proof that creativity, courage, and refusal to follow old rules could sometimes win where conventional power failed.

The daring pilots of Liner’s squadron had flown through fire and salt spray to change the way wars were fought — and in just three days, they rewrote the history of air combat.