How a Pilot’s Scrapped Idea Turned Into the Fastest Plane of World War II

War Untold / YouTube

The Rejected Design That Changed Everything

In the early 1930s, Britain’s Royal Air Force still relied on biplanes—slow, open-cockpit machines that looked like they belonged to another era. While other countries were moving toward faster monoplane designs, the British Air Ministry remained cautious, convinced that the old designs were still good enough. But one engineer, R.J. Mitchell of a small company called Supermarine, saw what others didn’t. The world was changing, and air combat would never be the same again.

Mitchell had earned his reputation building racing seaplanes for competitions such as the Schneider Trophy. Those sleek aircraft pushed the limits of speed and aerodynamics. In 1931, his Supermarine S6B set a world speed record of nearly 407 miles per hour—a remarkable feat at the time. That experience gave him a dangerous idea: what if a fighter plane could be built with the same principles as a racer? When Mitchell presented his concept, the Air Ministry dismissed it outright. They called it too complex and expensive, an unrealistic experiment.

Building a Fighter the Hard Way

Most people would have given up, but Mitchell wasn’t one of them. Instead, he redesigned his aircraft in secret, refining its curves, adjusting its wings, and improving every technical detail. His new project, the Type 300, was sleek, compact, and made almost entirely of metal. It had thin, elliptical wings designed to reduce drag and improve lift—features that would later define its beauty and performance.

To power it, he partnered with Rolls-Royce, which was developing a new 12-cylinder engine called the Merlin. The combination promised speed and reliability beyond anything in the air. But again, the Air Ministry wasn’t convinced. Only after Germany began rearming did officials reconsider. In 1934, they reluctantly gave Mitchell a small contract to build one prototype—just enough to see if his idea could even fly.

The First Flight That Silenced Doubt

The prototype was built in a small factory in southern England by a handful of dedicated engineers working under Mitchell’s watchful eye. Every bolt, every rivet, and every curve mattered to him. When the aircraft—now called the Supermarine Spitfire—finally rolled out for testing in 1936, test pilot Mutt Summers took it into the air for the first time. The flight was flawless. When he landed, he simply said, “Don’t touch anything.” That brief comment meant one thing: it was perfect.

The Air Ministry, once skeptical, suddenly realized they were witnessing something extraordinary. The aircraft could outclimb, outturn, and outrun anything else in the skies. Orders followed quickly, but mass production was slow. Supermarine was a small company unused to large-scale manufacturing, and building such a precise aircraft took time. Even so, Mitchell pushed through the challenges, despite quietly battling cancer. He continued to work until his health no longer allowed it, driven by one goal—to see his plane take flight.

The Battle That Proved Him Right

By 1938, the Spitfire was ready for service just as Europe edged closer to war. Mitchell didn’t live to see it; he died a year earlier. But his design would soon become Britain’s greatest defense. When Germany launched its air assault in 1940, the Spitfire and the Hawker Hurricane stood between Britain and invasion. The Hurricanes attacked bombers while the Spitfires faced the German fighters head-on.

In the skies above southern England, the Spitfire proved itself. Its agility, speed, and stability allowed British pilots to match and often outfly their opponents. One pilot described it as “wearing wings.” The Spitfire’s distinctive elliptical silhouette became a symbol of resistance, seen as a guardian of British skies. Its success in the Battle of Britain not only prevented invasion but also changed the course of the war.

A Legacy of Flight and Defiance

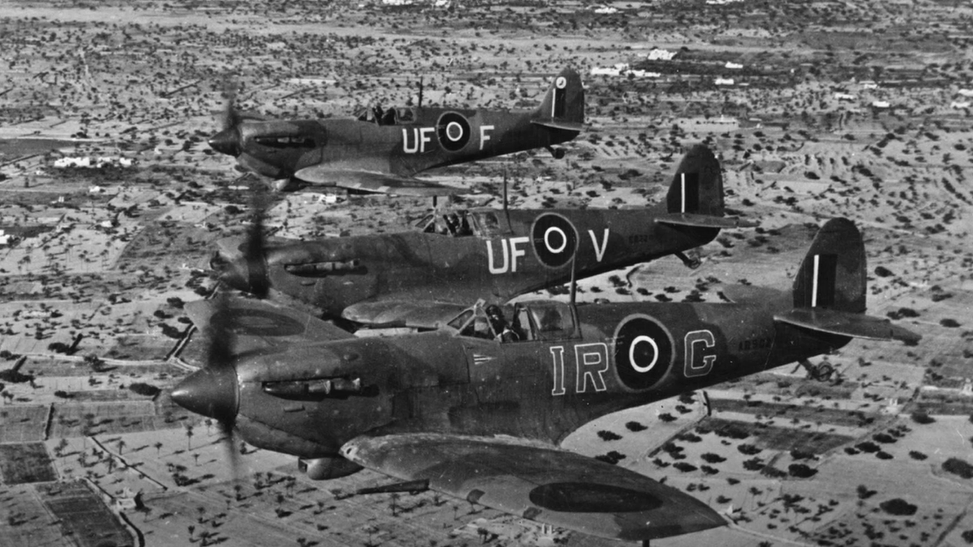

After Mitchell’s death, his assistant Joe Smith continued refining the aircraft. Over the years, engineers upgraded engines, strengthened frames, and improved weapon systems. Later models could reach speeds over 440 miles per hour, among the fastest piston-powered fighters ever built. More than twenty-four major versions appeared, flying across North Africa, Italy, France, and even deep into German airspace.

The Spitfire’s influence lasted long after the war. It continued flying into the 1950s and was used by countries around the world. Even today, when a Spitfire’s Rolls-Royce Merlin engine roars at an air show, people stop to look up. It’s more than nostalgia—it’s the living echo of one engineer’s determination to prove that innovation and courage could change history.