The Story of the Pilot Whose 200-Foot Bombing Runs Destroyed 12 Japanese Ships in Three Days

The War Files / YouTube

A New Dawn Over New Guinea

On March 3, 1943, dawn broke over Port Moresby, New Guinea, painting the sky with streaks of red and gold. Major Edward “Ed” Lana gripped the control column of his B-25 Mitchell bomber as its twin Wright Cyclone engines thundered to life. Behind him, eleven more bombers formed up, their propellers slicing through the morning haze. Out over the Bismar Sea, a Japanese convoy moved confidently toward New Guinea under heavy escort from destroyers and fighter planes.

They expected the usual high-altitude attacks—ineffective and distant. But what was coming would strike only 200 feet above the waves. Lana’s squadron planned to fly so low that the ocean’s spray would hit their windshields. Their bombs would not fall from the sky but skip across the sea like stones before striking their targets. It was a method so daring that many called it suicidal. Yet for Lana and his men, it was the only way to turn the tide of war.

The Birth of a New Strategy

The idea had taken shape months earlier under Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force. In 1942, American bombers had failed to stop Japanese convoys—only two ships sunk out of hundreds of attacks. The problem was height. Bombers flying safely at altitude gave enemy ships too much time to evade. Kenney needed something radical.

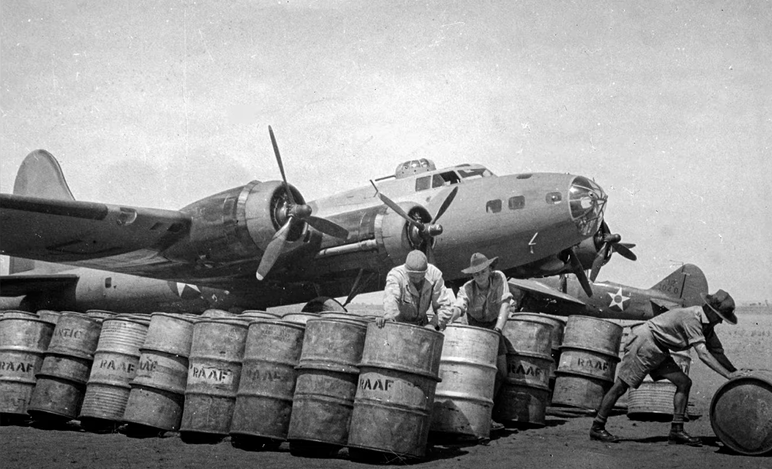

That answer came from Major Paul “Pappy” Gunn, a maverick engineer with a personal reason to fight—his family was held captive in the Philippines. Gunn transformed standard B-25 bombers into deadly gunships by removing their glass noses and fitting up to a dozen forward-facing machine guns. These aircraft could now strafe ships directly before releasing bombs that skipped across the water. He called them “Commerce Destroyers,” and they were unlike anything the Pacific had seen.

Training for the Impossible

To master this new form of attack, Lana trained his men relentlessly. They practiced on the wreck of the SS Pruth, a rusted steamer near Port Moresby, flying just above the surface and dropping practice bombs. They learned to aim by markings scratched onto their windshields rather than bomb sights. When one crew was lost during training, the others buried their comrades and returned to the skies the next morning.

Every pilot knew why. Japanese convoys were constantly reinforcing their troops in New Guinea. If those ships were not stopped at sea, the campaign—and possibly Australia—would be at risk. By late February, the squadron was ready for combat, confident that they could strike with deadly precision at low altitude.

The Battle of the Bismar Sea

On March 1, reconnaissance planes spotted a Japanese convoy leaving Rabaul: eight transport ships carrying nearly 7,000 troops and eight destroyers as escort. When weather cleared two days later, Kenney ordered the attack. At 10 a.m., American B-17s began bombing from 7,000 feet, scattering the convoy but causing few hits. The Japanese captains relaxed, believing they had survived—until the sea level came alive.

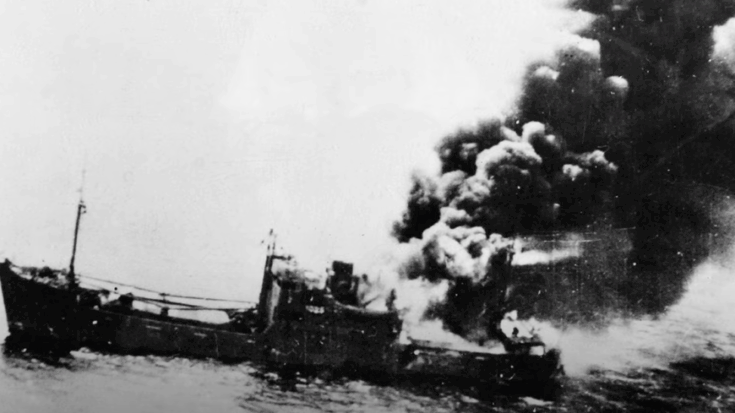

Australian Beaufighters swept in first, strafing decks with cannon fire. Seconds later, Lana’s B-25s roared in at 200 feet, guns blazing. Lana lined up a destroyer, his tracers ripping through its bridge before releasing two bombs that skipped once and struck the hull. The explosion tore the ship apart. Across the convoy, other bombers did the same—ships shattered, oil ignited, and fire spread across the sea.

Within fifteen minutes, eight transports and three destroyers were gone. By March 4, the last ships sank beneath the waves. Nearly 3,000 Japanese soldiers were lost. Allied casualties totaled only four planes and thirteen men.

Legacy of the Low-Level Raiders

The victory stunned both sides. What began as a desperate gamble became one of the most decisive air attacks in the Pacific War. Low-level skip bombing and forward-firing gunships became standard practice across Allied air forces. General Douglas MacArthur called the Battle of the Bismar Sea the decisive aerial engagement of the Southwest Pacific.

Major Edward Lana never saw the full impact of his innovation. He died in a training accident weeks later, his overloaded bomber crashing on takeoff. But his tactics lived on, shaping the way air power would be used for the rest of the war. What began 200 feet above the waves rewrote the rules of modern aerial warfare.