The Rare and Overlooked World War II Planes That Remain Largely Unknown

The Aerodrome / YouTube

When people think of World War II aircraft, names like the Spitfire, P-51 Mustang, or Messerschmitt quickly come to mind. These planes are remembered in books, films, and museum displays. Yet, many other aircraft carried out missions just as daring, though they never achieved the same level of recognition. Some were ahead of their time, some outdated when they entered combat, and others were simply unusual. What unites them is how they contributed to the war effort in ways history often overlooks.

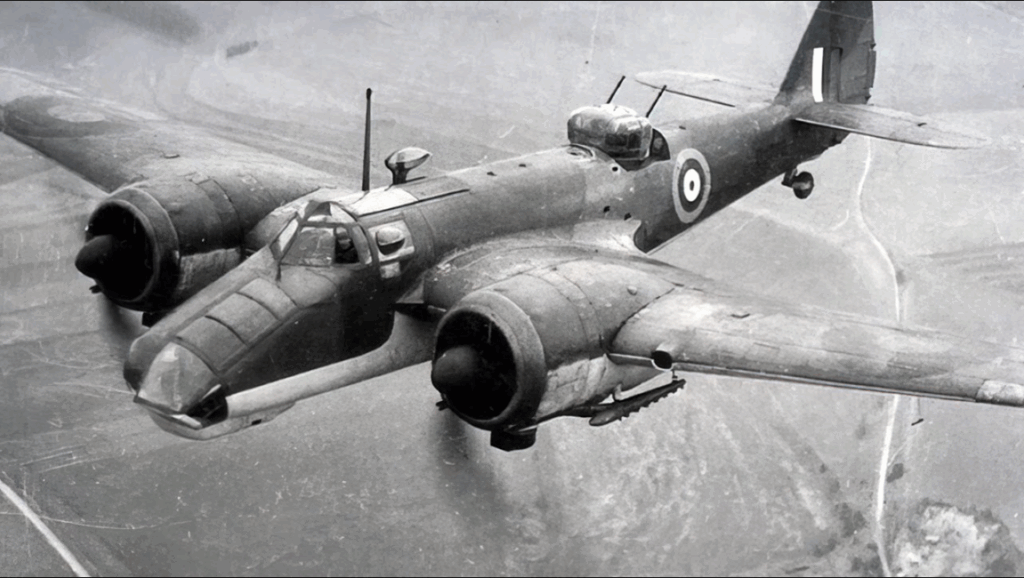

The Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim began life not as a bomber but as a civilian airliner. In the 1930s, it was a sleek passenger plane, boasting a speed of 280 miles per hour—faster than most fighters of that decade. The British Air Ministry quickly realized its potential for war and requested it be adapted to carry bombs.

Once converted, the Blenheim entered service as one of the fastest bombers in the world. With retractable landing gear, advanced propellers, and an electrically powered gun turret, it looked like the future of aerial combat. In its early days, it could outrun enemy interceptors. But as newer, stronger German fighters entered service, its defensive armament of light machine guns proved inadequate. Despite this, the Blenheim carried out reconnaissance flights, bombing raids, and risky daylight operations when Britain was most vulnerable. Over 4,000 were produced, and they flew in campaigns from Europe to Asia.

The Westland Lysander

The Westland Lysander was first designed for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. Its unusual design—large wings and fixed landing gear—gave it the rare ability to take off and land in extremely short distances. That quality soon found it a new role: delivering and collecting secret agents in occupied Europe.

Painted black and flown at night, Lysanders slipped across enemy lines, touching down in small fields where resistance groups waited. Crews installed a built-in ladder so that spies could climb aboard quickly. These missions were dangerous: pilots flew in darkness with minimal instruments, often in poor weather, and faced the constant risk of anti-aircraft fire or night fighters. Squadron Leader Hugh Verity became known for completing more than thirty such operations, at times landing under fire and barely escaping. By war’s end, the Lysander had carried out hundreds of secret flights, extracting downed airmen and keeping underground networks supplied.

The Fiat CR.42 Falco

At a time when most nations were moving to fast monoplanes, Italy introduced the Fiat CR.42 Falco, a biplane fighter. Though it seemed outdated, the aircraft had advantages. Its lightweight frame and double wings allowed it to turn tighter than most modern fighters, making it dangerous in a dogfight. Allied pilots often underestimated it until discovering how agile it could be.

The Falco was durable as well. Its fabric-covered wings absorbed stress that might break a heavier aircraft. Italian pilots used it effectively in North Africa and the Mediterranean, scoring victories against better-armed opponents. Still, it carried only two machine guns, leaving it underpowered against aircraft like the Spitfire, which had quadruple that firepower. More than 1,800 CR.42s were built, serving not just Italy but also Hungary, Belgium, and Sweden.

The Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish looked outdated even before the war began. It was a biplane covered in fabric, slow and exposed to the elements. Pilots nicknamed it the “stringbag” because it could carry a wide variety of weapons. Despite its appearance, the Swordfish achieved one of the most famous naval strikes of the war.

In 1941, German battleship Bismarck threatened Allied shipping in the Atlantic. Modern warships failed to stop it, but Swordfish torpedo bombers launched in foul weather and attacked. Against heavy fire, one torpedo struck the rudder, crippling the battleship. British warships then closed in and sank Bismarck. The Swordfish also crippled the Italian fleet at Taranto and later flew missions from Arctic carriers. By the war’s end, these “obsolete” biplanes had sunk over 300,000 tons of enemy shipping.

The Cierva C.30A Autogyro

Before helicopters became practical, militaries experimented with autogyros—strange hybrids between airplanes and rotorcraft. The Cierva C.30A had an open cockpit and a free-spinning rotor above its frame. Though fragile in appearance, it was stable and safe to fly.

The Royal Air Force used the autogyro for an important but little-known task: radar calibration. Pilots flew steady circuits around radar towers so operators could fine-tune their equipment. This routine work gave Britain a major advantage during the Battle of Britain, as radar stations could detect approaching German formations early. Those precious minutes allowed British fighters to be scrambled in time to meet the threat. The humble autogyro, though not glamorous, quietly played a role in one of the war’s most decisive defenses.