How Britain’s Secret WWII Tech Made Their Fighters Practically Invisible to German Bombers

Britain At War ! / YouTube

During the darkest hours of World War II, British cities faced relentless night raids. Air raid sirens pierced the night, fires burned across urban centers, and searchlights cut through the darkness. For Royal Air Force night fighter crews, this was a perilous environment. The same conditions that could help them spot enemy bombers also made their own aircraft highly visible. While radar existed, much of the fighting relied on what pilots could see with their own eyes. A night fighter closing in on a formation of German bombers often found that the attackers were detected first. Reports from German gunners suggested they could spot enemy planes at distances of around 2,000 yards, giving them time to aim and fire before being engaged.

The challenge was simple but deadly: the night fighter had to remain unseen until the very last moment. Any silhouette breaking against the horizon could draw fire from ground defenses or bomber gunners. Even with dark paint schemes, the contrast between aircraft and night sky often betrayed the attacker. Every approach became a tense race: would the fighter spot the bomber before being spotted itself? Amid these high-risk skies, one British inventor proposed a radical solution: instead of trying to hide in shadow, why not use light to blend in?

Jeffrey Pike and the Concept of Counter-Illumination

The man behind the idea was Jeffrey Pike, a British inventor and educationalist born in 1893. Pike had gained recognition in World War I for daring exploits and had introduced innovative educational reforms. By the Second World War, he was working within Britain’s research and development apparatus, producing both ambitious projects and more modest but ingenious devices. His interest in optical camouflage and the way the human eye perceives objects against complex backgrounds led him to study how aircraft might become less visible at night.

Pike understood that reducing the distance at which an attacker could see a night fighter would greatly improve survival chances. If a bomber gunner normally detected a plane at 2,000 yards, lowering that range to 600 yards could give the night fighter a crucial few seconds to engage. He drew inspiration from nature, where some marine animals use photophores to match the brightness of the water when seen from below. Applying this principle to aviation, Pike proposed mounting forward-facing lamps on the nose and leading edges of night fighters. These lights would automatically adjust their brightness to match the sky, effectively erasing the aircraft’s silhouette.

Experiments and Tactical Implications

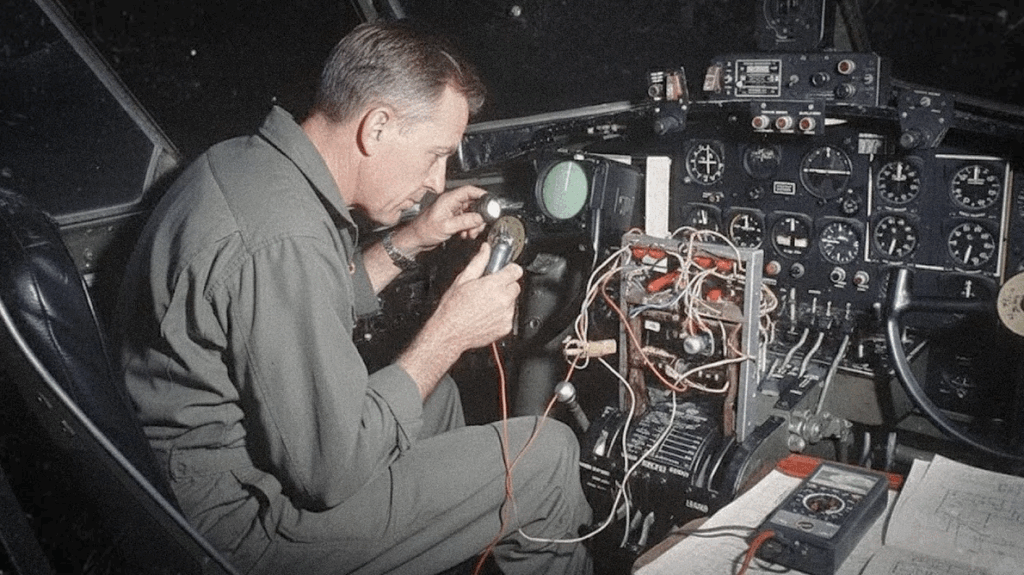

Pike’s concept, sometimes referred to as Yehudi lights, was tested in Britain and later in the United States. The idea was simple in principle but technically complex: sealed beam lights linked to sensors would adjust in real time, reducing contrast between the aircraft and its background. Tests suggested dramatic results. In one trial, detection ranges fell from about 12 miles to just 2 miles, a reduction of nearly 70 percent. For night fighter crews, this meant a far better chance of approaching enemy bombers undetected and surviving the encounter.

The operational context of 1941 made this idea particularly relevant. Radar was still in its infancy, and night fighters often relied on moonlight, searchlights, and pilot skill. Pike’s system promised to shift the advantage toward the intercepting aircraft. Although records are incomplete, Air Ministry documents indicate that British researchers seriously considered counter-illumination to reduce visual detection ranges. Whether the system was widely deployed remains uncertain, but the experimental insights shaped thinking about night combat. In both European skies and the Atlantic, where aircraft faced darkness, clouds, and moonlight reflections, even small reductions in visibility could be decisive.

Limitations and Legacy

Several factors prevented wide adoption of Pike’s lighting system. By the mid-1940s, radar technology had advanced, making visual detection less critical. Practical challenges, such as wiring, calibration, maintenance, and aerodynamic drag, made large-scale implementation difficult. Additionally, wartime priorities emphasized reliable systems over experimental technologies, and much of the research remained classified. Still, the principle of blending brightness with the background influenced later developments in visual stealth.

Though Pike died in 1948 at the age of 54, his ideas endured. Modern stealth technology, including some drones and active lighting systems, draws on the same principles of counter-illumination and reduced contrast. His work highlighted that night fighting relied not only on weapons and speed, but also on perception, shadows, and visibility. Each forward-facing lamp was more than a source of light; it represented an understanding of how the human eye could be tricked to give pilots a life-saving advantage. Pike’s efforts illustrate how ingenuity and scientific insight shaped aerial warfare, and even if his lighting system never became standard, its influence can still be seen in the evolution of aircraft stealth.