This Wellington Pilot Flew 90 Miles With His Cockpit Blown Off and Landed Blind With Only His Co-Pilot’s Voice to Guide Him

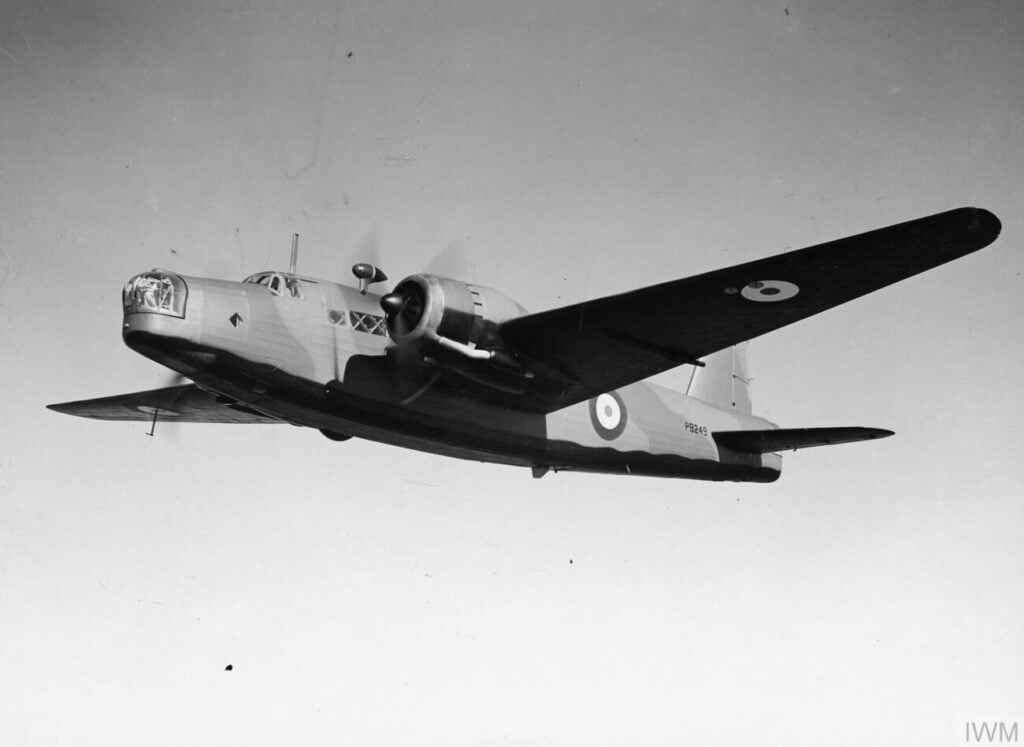

Royal Air Force official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Stories from early 1941 often show how ordinary airmen were pushed into situations far beyond anything training could prepare them for. One of the clearest examples comes from Flight Sergeant James Allen Ward, a New Zealand pilot flying a Wellington bomber during a night attack on Hamburg. What happened to him on this mission became one of the most extreme survival events recorded in Bomber Command.

A Sudden Disaster in the Dark

The Wellington shook as the first bursts of German fire appeared beneath its wing on the night of 13 April 1941. Ward felt each blast through the controls and through his body as he tried to guide the bomber through shifting altitudes. The aircraft carried six men and a full bomb load toward Hamburg’s oil areas, following a route that took them straight into heavy defenses.

The Wellington’s special framework could absorb damage better than most early war bombers, but it offered no safety when a well-aimed 88 mm shell burst at the right height. German gun crews had spent years refining their fire control methods, using instruments and practiced timing to fill the sky with deadly fragments. Ward tried to keep the aircraft unpredictable, but a single calculated burst ended all stability.

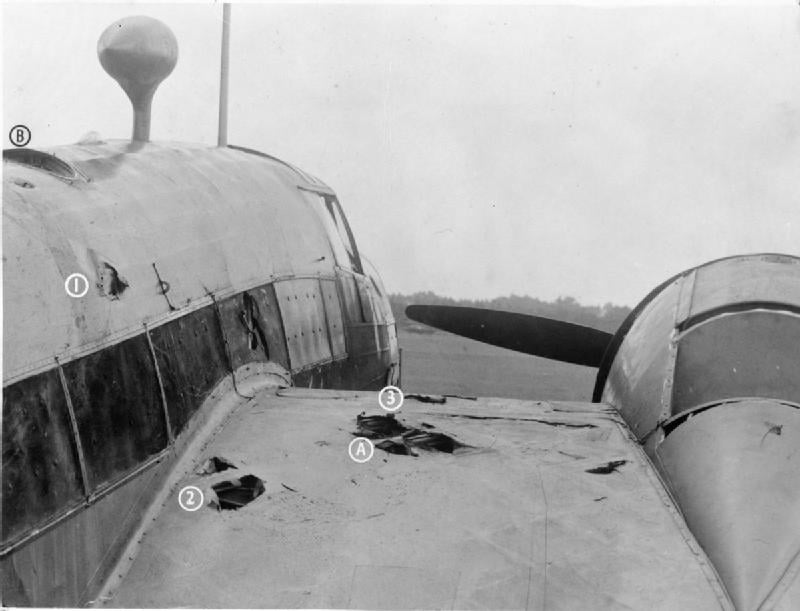

The Cockpit Is Destroyed

Without warning, a shell exploded less than twenty feet ahead of the cockpit. The front of the aircraft vanished in an instant. Wind roared through the opening, instruments shattered, and freezing night air rushed inside. The force tore through metal, controls, and the crew. Ward was hit in the face, and blood poured into his eyes. He could no longer see anything.

The aircraft dropped sharply as the control system faltered. Ward gripped the column as best he could, fighting shock and the violent cold pouring through the torn cockpit. The Wellington dived toward the darkness below while both engines screamed at full power.

A Pilot Shaped by Unexpected Circumstances

Ward’s path to this moment had begun far from war. Born in Wanganui, New Zealand, in 1920, he had grown up on a quiet farm. He expected a life shaped by simple routines rather than aviation. When conflict began in Europe, New Zealand committed airmen and resources to support Britain, and Ward volunteered for aircrew duties in 1940.

He passed the medical tests and moved through basic flight training, first on small biplanes and then on more advanced aircraft. In Canada, he learned night navigation, instrument flying, and formation procedures. The lessons were demanding because the risks in operations were high, and any weakness could be fatal.

Joining a Frontline Squadron

By early 1941, Ward reached Britain and joined No. 75 Squadron, a New Zealand unit flying Wellington bombers from Norfolk. Operations were frequent, and losses were steady. Crews often avoided forming close bonds because many newcomers vanished within days. Ward flew his first missions in March and quickly saw how unforgiving night attacks over Europe could be.

On the day of the Hamburg raid, the squadron gathered for the target briefing. The room smelled of damp uniforms and worry familiar to anyone who had flown repeated missions. Hamburg meant strong defenses, searchlights, and patrols. The purpose of the attack was to damage oil facilities, though accuracy at night remained poor. Still, the crews followed orders and prepared to go.

The Crew Begins the Mission

Ward’s second pilot that night was Sergeant Johnny Lawson, another young New Zealander who would play a crucial role after the cockpit was destroyed. The rest of the crew occupied their positions as the Wellington lifted into fading daylight. They crossed the North Sea and approached the German coast, where defenses thickened.

When the 88 mm shell struck and tore away the cockpit, Lawson saw at once that Ward could not see. With freezing wind blasting into the aircraft and the controls failing, the crew’s survival depended on Lawson guiding Ward by voice alone. The Wellington was torn open, the pilot was blind, and they were still deep inside enemy territory.