What Happened To The Forgotten “Twin Spitfires”

YouTube / Rex's Hangar

In the late 1930s, with war looming over Europe, Britain’s Air Ministry issued Specification F.18/37—calling for a single-seat fighter capable of reaching 400 mph at 15,000 feet and armed with twelve Browning .303 machine guns. This requirement would ultimately lead to the Hawker Typhoon—but Supermarine, fresh off the success of the Spitfire, had ambitious ideas of its own.

A Radical Twin-Engine Design

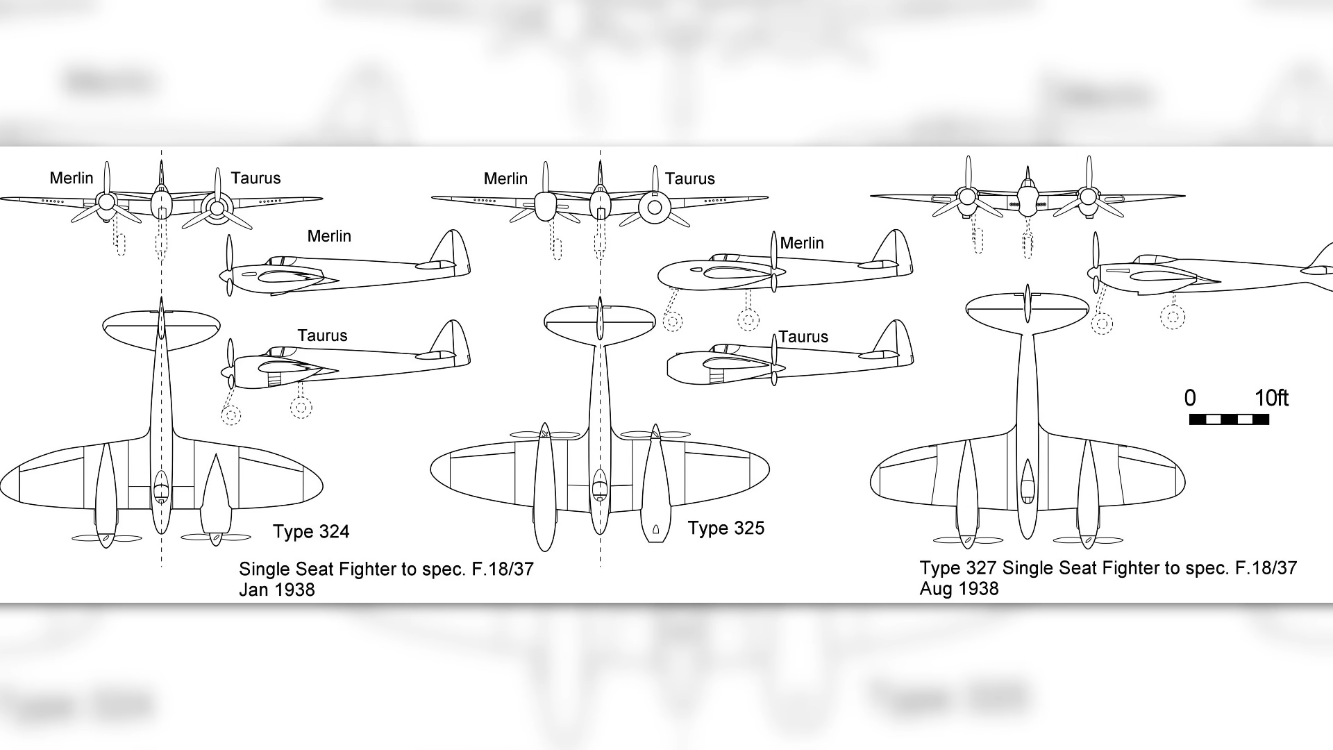

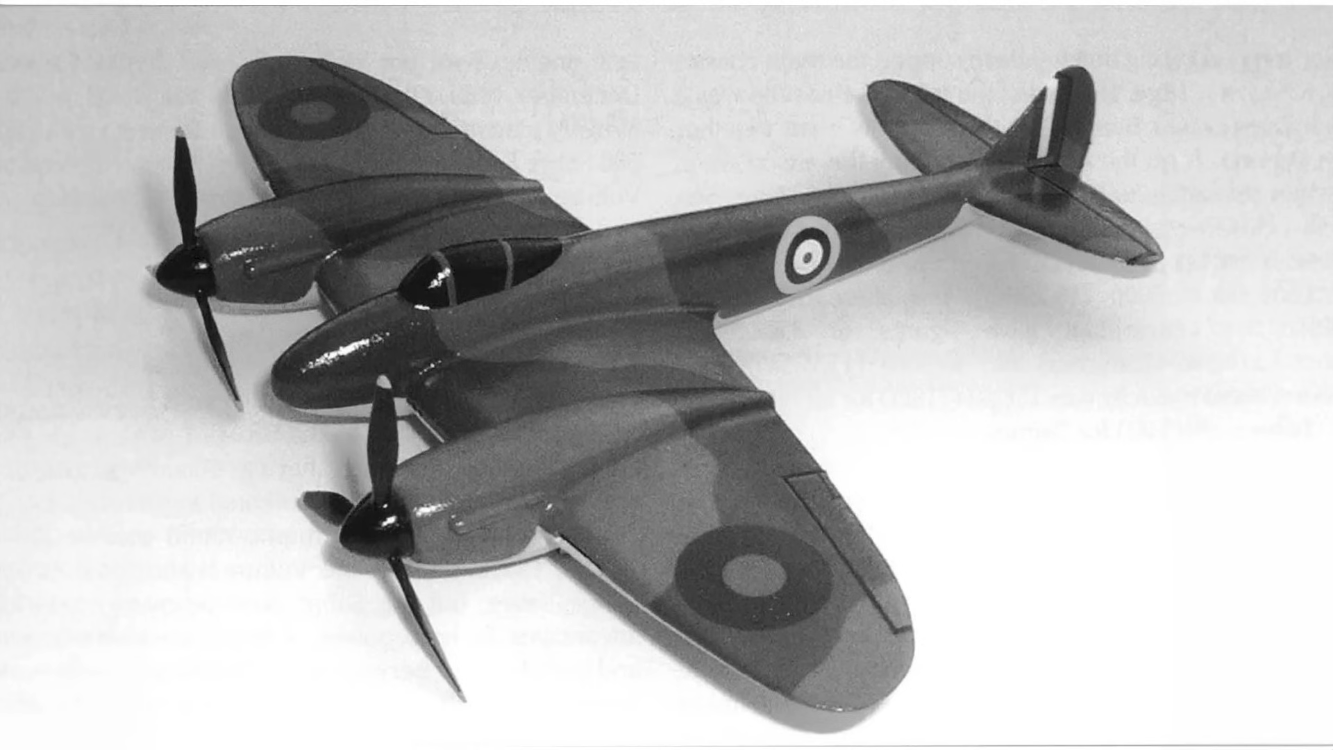

Supermarine submitted two proposals: the Type 324 and Type 325. Both were twin-engine fighters, a daring departure from the single-engine Spitfire design. The Type 324 used a traditional “tractor” layout (engines pulling the aircraft), while the Type 325 employed a “pusher” setup (engines pushing from the rear). Despite their extra engines, both aircraft were only slightly larger than the Spitfire.

The twin-engine layout offered several advantages—improved visibility with no central propeller, easier takeoffs thanks to counter-rotating propellers, and better handling from tricycle landing gear. Combined with the monocoque fuselage and single-spar, all-metal wing borrowed from Spitfire development, the designs promised exceptional performance.

Engineering Ambition

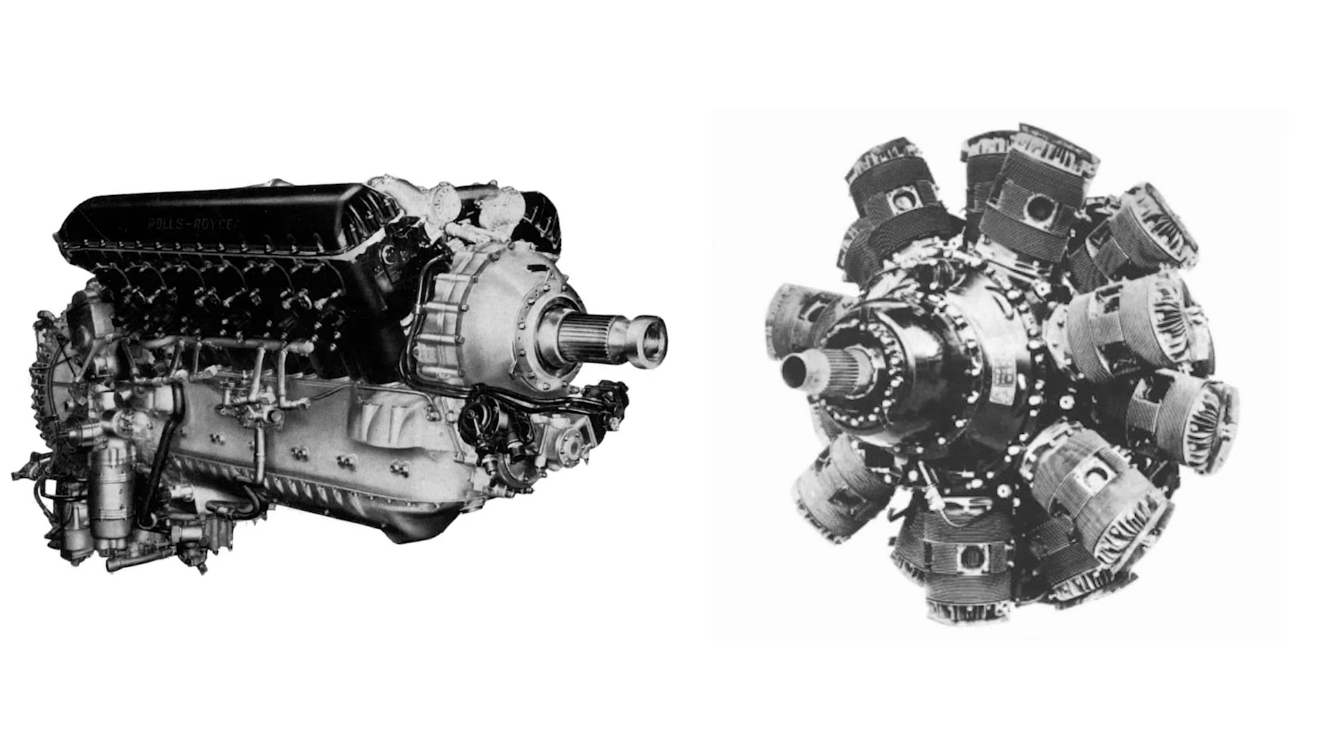

The 324 was expected to use the powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, giving it a projected climb rate of 4,900 feet per minute and a ceiling of 43,500 feet. An alternative using the Bristol Taurus radial engine was also proposed, though it offered lower performance.

Supermarine’s engineers applied lessons from both the Spitfire and their experimental bomber projects, focusing on simplicity and strength. They even reduced rivet counts by up to two-thirds in some areas to ease production. The aircraft’s wings would house radiators, undercarriage, guns, and fuel tanks—compact and efficient for its time.

The Problem of Firepower

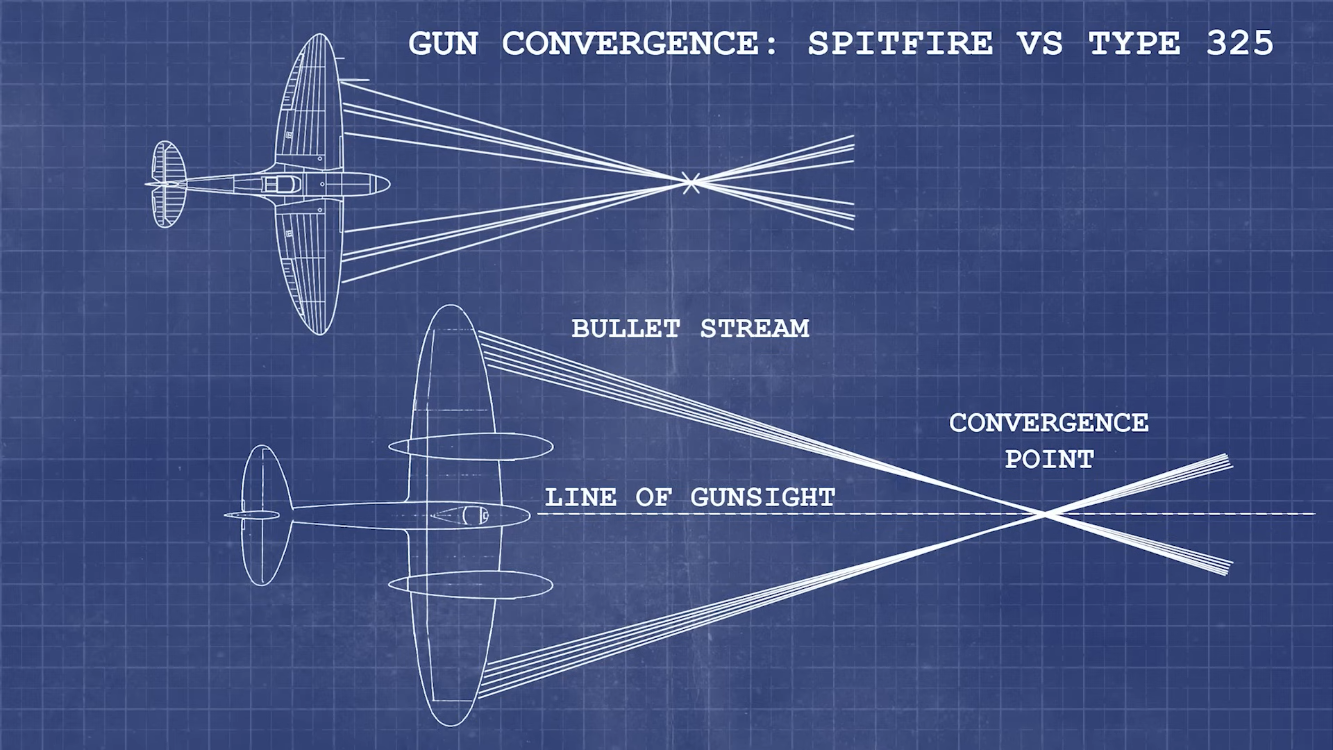

Despite its promise, the twin-engine Supermarine designs hit a critical snag: gun convergence. Mounting twelve machine guns in the wings made accurate fire difficult, especially since the guns were far outboard. The Air Ministry ultimately rejected the proposals in favor of Hawker’s single-engine design, though the concept wasn’t entirely dead.

The Final Attempt: Type 327

By 1938, as the RAF turned its attention to fighters armed with 20mm Hispano cannons, Supermarine reworked its idea into the Type 327. This version carried six 20mm cannons mounted closer to the fuselage for accuracy and retained the Merlin engines. The pusher concept was abandoned entirely.

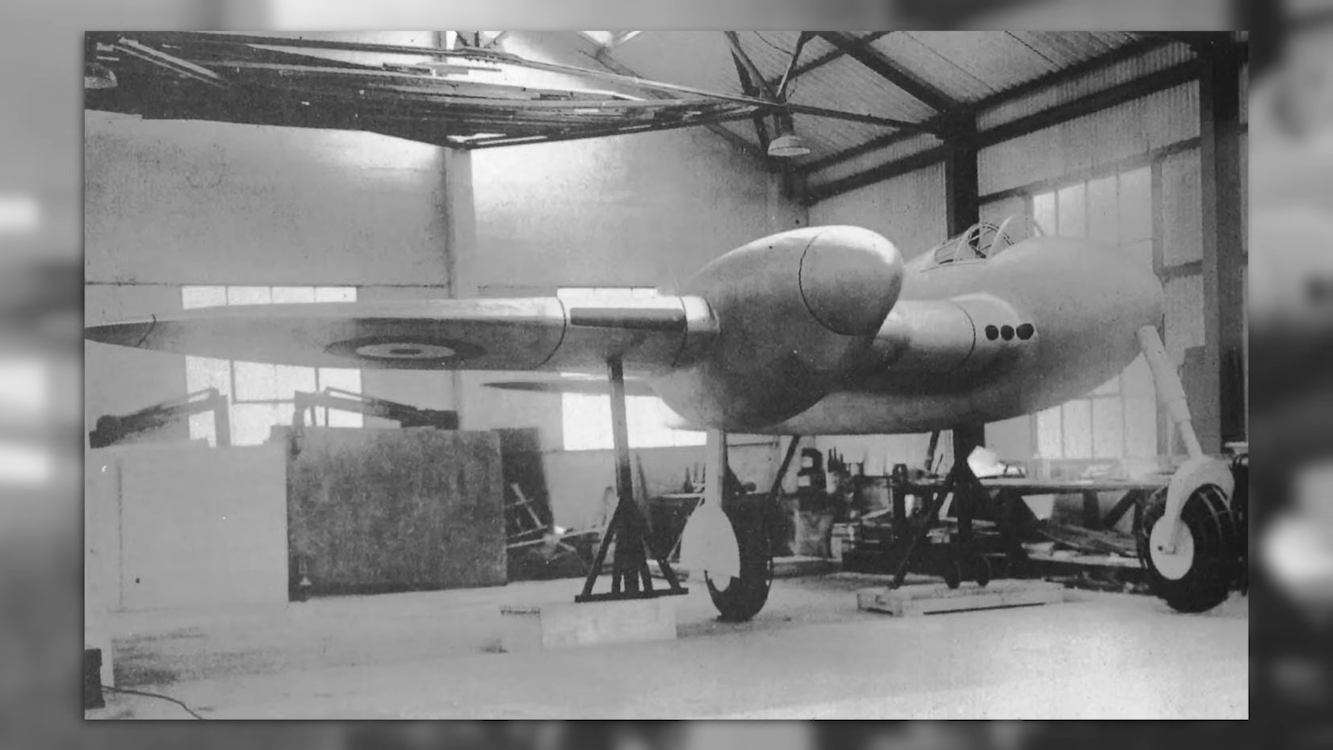

A full-scale mockup was built to improve Supermarine’s chances, but once again the design was passed over. The Air Ministry cited concerns over ammunition storage and Supermarine’s slow development pace. With war approaching, all resources were redirected to Spitfire production—a decision that would prove essential to Britain’s survival.

What Might Have Been

The “Twin Spitfires,” as later enthusiasts called them, never left the drawing board. But had they flown, they might have combined Spitfire agility with twin-engine reliability—perhaps rivaling aircraft like the Westland Whirlwind or de Havilland Hornet.

In the end, the project’s failure was a blessing in disguise. The overwhelming demand for Spitfires during the war would have quickly sidelined any twin-engine variant. Still, the Supermarine Type 324, 325, and 327 remain fascinating “what-if” chapters in British aviation history—proof that even legends like the Spitfire had experimental cousins waiting in the wings.