The Strange Reason U.S. Gunners Fired Behind Enemy Planes — And Ended Up Shooting Down Twice as Many Planes

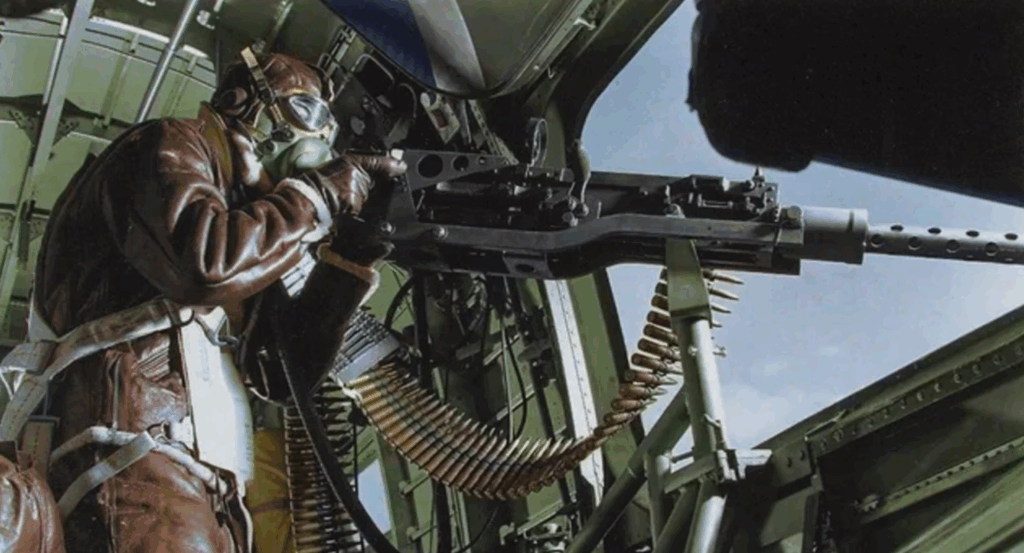

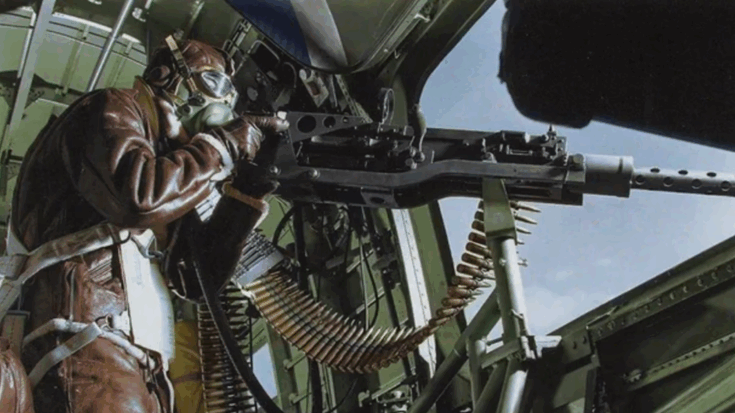

The War Files / YouTube

In the frozen skies over Europe during the Second World War, bomber crews faced a deadly truth: they were flying targets. German fighters attacked from all directions, and the survival of every crewman depended on the skill of the men behind the machine guns. Yet one of the most successful shooting techniques in aerial combat sounded completely illogical. American gunners learned that to hit a fast-moving enemy, they had to aim behind it—not ahead. That strange method, born in the Nevada desert, would double their accuracy and change air combat training forever.

The Problem in the Sky

On October 3, 1943, thousands of feet above the North Sea, a U.S. waist gunner lined up his sights on an approaching German fighter. His instincts told him to aim directly at the enemy’s nose, but his training told him otherwise. He aimed six aircraft lengths behind—and seconds later, the fighter exploded in midair. That moment proved what seemed impossible: the human instinct to aim straight at a moving target would almost always fail in aerial combat.

This discovery came from years of testing and an urgent wartime need. In early 1941, as America prepared for war, Colonel Martinez Stenith stood in the middle of an empty desert outside Las Vegas. The U.S. Army Air Corps had no proper school for aerial gunnery—no standardized curriculum, no scientific method to teach how to shoot from one moving aircraft at another. The British had already suffered heavy losses from untrained gunners. The Americans decided they would not make the same mistake.

Building the School That Taught the Impossible

Construction crews arrived in March 1941, turning that barren desert into a sprawling base of classrooms, firing ranges, and barracks. Within months, the Las Vegas Army Airfield became the center of a new science—how to aim from the air. When America entered the war after Pearl Harbor, the school rushed into action, training hundreds of recruits who arrived fresh from farms and small towns.

The early lessons used shotguns and clay pigeons to teach “leading” a target, but when the guns were mounted on moving trucks to simulate aircraft speed, everything changed. The students suddenly couldn’t hit anything. Confusion spread until one instructor, Sergeant Robert Hayes, explained the hidden physics. A bullet fired from a bomber did not travel straight—it carried the forward motion of the plane, curving slightly in flight. That meant the faster the bomber moved, the farther behind the target the gunner had to aim. To hit a fighter sweeping past at 300 miles per hour, you had to shoot where it was, not where it is.

Turning Theory into Combat Skill

This became known as position firing, and it was drilled into every new gunner. Trainees studied diagrams, deflection charts, and tables showing exactly how far to aim behind at different angles. At first, it seemed absurd—some attacks required aiming as much as twelve aircraft lengths behind—but results proved otherwise. By the summer of 1942, the school produced six hundred new gunners every five weeks.

Training was relentless. Students learned aircraft recognition, ballistics, and weapon maintenance before moving to simulators and live-fire practice. The Waller trainer—a mechanical simulator projecting enemy fighters onto a curved screen—helped them master split-second reactions. By week five, they were firing from real bombers at towed targets, with color-coded bullets to track accuracy. Those who passed earned their wings and joined crews bound for combat over Europe.

From the Nevada Desert to the Skies Over Germany

By mid-1943, over 57,000 aerial gunners had graduated from American schools. When 376 B-17 bombers struck German targets that August, hundreds of waist gunners used the new method instinctively. They aimed behind attacking fighters and destroyed twenty-seven enemy planes, even while losing sixty bombers. The technique worked—mathematics had beaten instinct.

Soon, technology joined the lesson. In late 1943, a new invention, the gyro gunsight, used spinning gyroscopes to calculate deflection automatically. Gunners no longer had to guess—the sight projected a moving reticle showing exactly where to aim. Accuracy doubled almost overnight, freeing airmen from the mental strain of complex calculations in battle.

The Evolution of Precision

By 1945, over 200,000 American gunners had been trained. New systems like Operation Pinball, using real aircraft coated with armor and sensors, pushed realism further and improved accuracy by nearly forty percent. Later bombers, like the B-29, introduced remote-controlled turrets linked to onboard computers that calculated bullet drop and deflection automatically.

What began as an experiment in the Nevada desert became one of the most effective training revolutions in modern warfare. The lesson was simple but profound: instinct alone could not win in the sky. Success belonged to those who trusted science, training, and precision—to those who learned that sometimes, survival means aiming behind the enemy, not at them.