The Reason F4F Wildcat Pilots Suffered So Much

The Aerodrome / YouTube

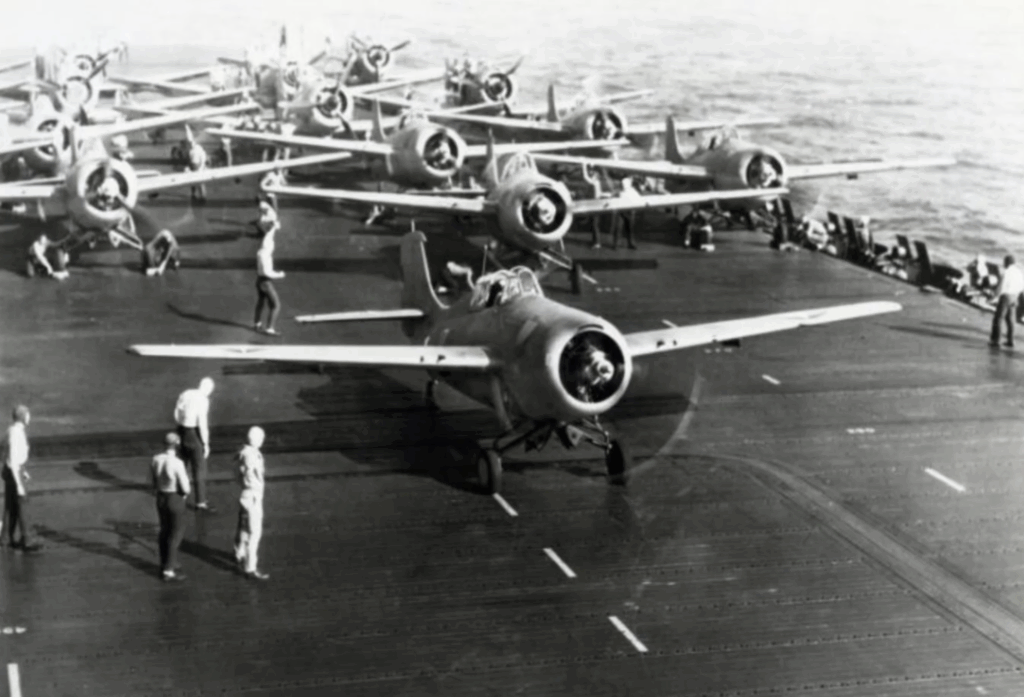

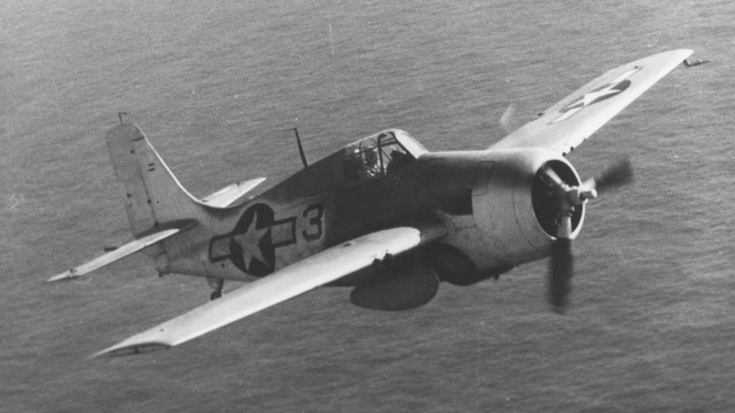

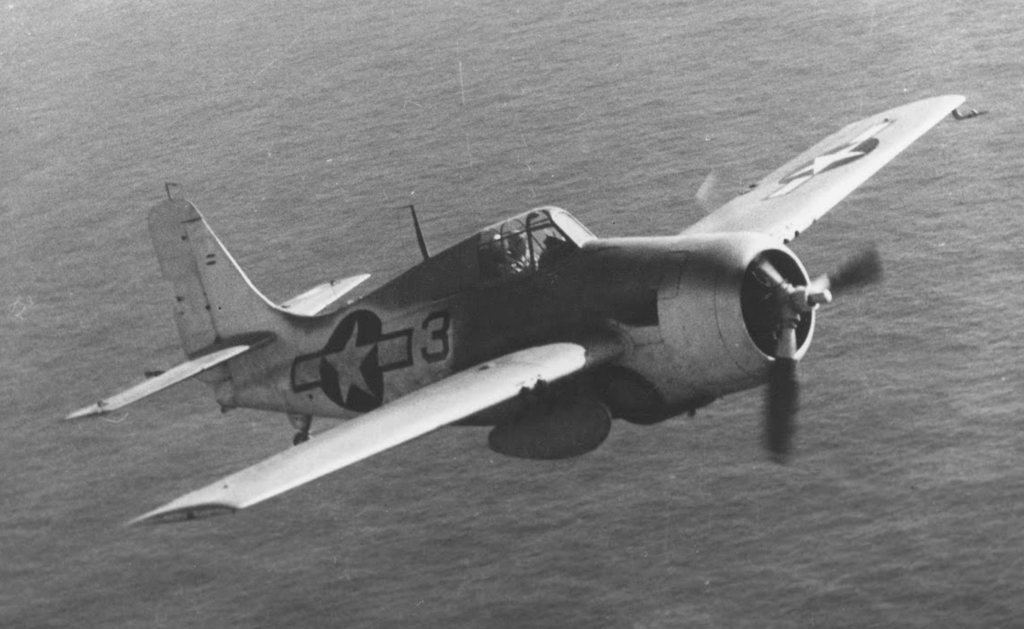

In the early years of the Pacific War, a single American fighter stood between the advancing Japanese military and Allied hopes for holding the Pacific. This was the Grumman F4F Wildcat—a tough but outdated aircraft sent into the worst fighting of the war. American pilots flying it found themselves outmatched, underprepared, and often outnumbered. Yet, they still flew into combat, trying to hold the line until better aircraft arrived.

The Wildcat entered service in 1940, during a transitional period in aviation. Grumman had only recently moved from building biplanes to monoplanes, and the Wildcat carried elements from both eras. It had heavy machine guns and folding wings that were ideal for aircraft carriers. But it also used hand-cranked landing gear, which required pilots to manually turn a lever thirty times while flying and watching for enemy planes. It was a fighter built under pressure, not perfection.

Facing a Superior Enemy

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Wildcat was rushed into action. But only about half the number originally ordered were actually delivered in time. Pilots, many of whom had only trained on biplanes, suddenly found themselves in the air against a much more advanced enemy aircraft—the Mitsubishi Zero. The Zero was faster, more agile, and had better climb performance. It was flown by extremely experienced Japanese pilots, many of whom had gone through a selective training process that produced some of the best aviators in the world. Early Wildcat pilots were simply not ready for what they faced.

The Wildcat had originally been meant as a stopgap until better planes could arrive. Those improved fighters—like the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair—came later in the war. But during the initial and most difficult phase of the conflict, the Wildcat was all the U.S. Navy had available for carrier combat.

Limited Numbers, High Losses

The British were actually the first to use the Wildcat in combat. They received them under the name Martlet and scored the plane’s first kill on Christmas Day 1940, when one shot down a German bomber. In American hands, Wildcats were in short supply and poorly positioned when the war began. At Wake Island and Hawaii, 16 Wildcats were destroyed on the ground during the initial Japanese attacks, and only a handful survived to fight back. In one early example of bravery, a Wildcat pilot managed to sink a Japanese ship by hitting its depth charges, though he was later killed when the island fell.

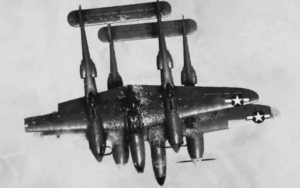

The first major American carrier operation involving Wildcats began in early 1942. Lieutenant Edward “Butch” O’Hare earned a Medal of Honor for shooting down five enemy bombers in one mission. But as the war went on, the Wildcat was thrown into increasingly brutal air battles. At the Battle of Coral Sea, the Wildcat gained a brief upper hand by catching enemy fighters off guard at high altitude. But that was rare. At Midway, Wildcat pilots learned firsthand how severely the Zero outperformed their aircraft.

Tactics and Technology Challenges

The Wildcat did have one major advantage—it could take damage. Unlike the lightly built Zero, it had armor and fuel tanks that sealed themselves if punctured. This gave pilots a better chance of surviving hits. But other issues plagued them. For example, the Navy’s ZB homing system, meant to guide pilots back to their carriers, often failed. It gave no accurate direction, and disoriented pilots frequently flew the wrong way. In one case, an entire squadron ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean because the system led them off course.

Firepower was another challenge. Early Wildcats had four heavy machine guns, each with 450 rounds. Later versions had six guns, but the total ammunition stayed the same, meaning each gun had less ammo and shorter firing time—about 15 to 20 seconds total. Many pilots found themselves in the middle of dogfights with no rounds left.

Bravery and Hard Lessons

As the Guadalcanal campaign began, Wildcat pilots flew constant missions in terrible conditions. The tropical humidity required the guns to be coated with oil to prevent rust. But when they climbed to higher altitudes, the oil could freeze and jam the weapons, leaving pilots unable to fire when it mattered most. Despite these setbacks, experienced pilots began to find ways to use the Wildcat’s strengths. Its rugged frame allowed it to survive hard landings or crash with less risk to the pilot. And it could dive away from Zeros, which were more fragile and couldn’t handle the stress of steep dives.

Veteran pilot John Thach created the “Thach Weave,” a defensive maneuver where two Wildcats would cross paths to trap an attacking fighter in the other’s sights. This tactic, along with growing teamwork and better shooting skills, helped American pilots survive long enough to wear down their enemies.

The Human Cost

The early stages of the war were especially hard. Replacement pilots had very little training—some had only enough hours to learn basic takeoff and landing before they were sent into real combat. The results were tragic. On days when coast watchers failed to report incoming attacks in time, Japanese raids tore through unprepared Wildcat squadrons. During the Guadalcanal campaign alone, over 100 Wildcats were lost, along with many of their pilots.

Some stories from the time were extraordinary. One pilot, after running out of ammunition, rammed an enemy plane midair and survived. Another used his landing gear to strike a bomber repeatedly until it went down. Yet these actions came at a steep cost. While American factories could replace planes quickly, Japan struggled to replace its experienced airmen. The sacrifices made by Wildcat pilots drained Japan’s trained forces. Those pilots endured the worst phase of the war, fighting with what little they had and holding the line until better aircraft and reinforcements arrived.