One Woman’s Ingenious Fix Stopped Spitfires from Failing — Pilots Laughed at First

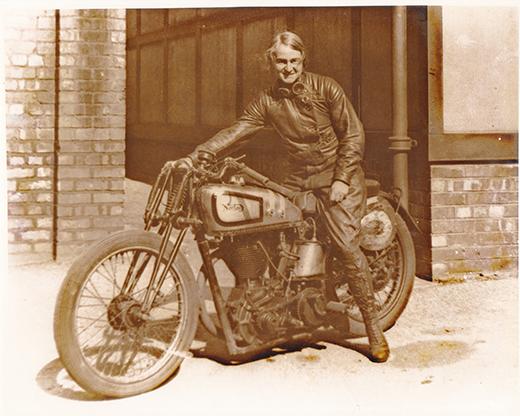

Photographer not known, but picture is believed to date from the 1930s., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Fatal Pause in the Sky

January 1941. Snow covered the grass at RAF Biggin Hill. Spitfires streaked across the winter sky, chasing German Messerschmitts. British pilots practiced maneuvers they had been drilled on: half-rolls, positive-G pulls, careful adjustments. Yet every so often, a Merlin engine would falter. A split-second loss of power in a dive could turn a pursuit into disaster. Pilots would hit the throttle, feel the propeller blur, and curse the moment the engine coughed. The enemy would slip away. On the flight line, frustration was growing, and it was clear the solution needed more than training—it needed engineering.

Enter Beatrice Shilling, a small, determined engineer with the Royal Aircraft Establishment. She arrived on a motorcycle carrying a canvas bag of tools, brass rings, and a plan. Shilling knew the problem: the early Merlin engines used float-type carburetors, which could flood the fuel jets when the plane was pushed into a dive. The Germans had an advantage with their fuel-injection engines, but the Spitfires could be made competitive. What the RAF needed was a field-ready solution, simple enough for a line mechanic to install between sorties, yet reliable in the sky.

The Ingenious Washer

Station engineers greeted Shilling with skepticism. “You’ve come two hundred miles to give us… washers?” one asked. She calmly corrected him: “Restrictors. One thin ring with a carefully calculated hole. It won’t make your Merlin clever, but it will make it behave.” On a small bench, she demonstrated how the brass orifice worked. In normal flight, fuel flowed freely to the jets. In a dive, the fuel surge was capped by the ring, preventing the engine from choking while still allowing full power in level flight. Pilots stared, some chuckling. The fix seemed too modest to matter.

Installation was straightforward. A fitter inserted the restrictor, torqued the union, safety-wired the banjo, and tested the engine. The Merlin idled steadily and ran at full power under aggressive maneuvers. The pilots, still cautious, tested it in flight. For the first time in months, they pushed the nose down in a controlled dive, held negative-G, and the engine held. Nervous laughter turned to relief. The Spitfire was no longer at a disadvantage in that critical moment, and the second they had once lost in every fight returned.

From Skepticism to Standard

Shilling traveled from Tangmere to Northolt, Debden, and beyond, installing the restrictor and recording results for the RAE. Her notes tracked fuel behavior, throttle settings, and temperature ranges, providing line crews with precise guidance. Squadrons that had mocked the washer began requesting it for every aircraft. By March 1941, the modification spread across Spitfires and Hurricanes. Losses in dives decreased, engagements became fairer, and pilots regained confidence. The simple orifice became known as “Miss Shilling’s orifice,” a mix of respect and RAF humor.

Her influence extended beyond the hardware. Pilots who once hesitated during negative-G maneuvers now flew more aggressively, matching German tactics. Engineers learned the value of small, practical solutions on the front line. While long-term fixes like pressure carburetors were in development, Shilling’s work gave immediate results. A simple, precisely drilled brass ring changed how air combat was fought, reducing wasted seconds and improving survival.

Legacy on the Flight Line

Beatrice Shilling never sought fame. She rode motorcycles, measured fuel flow with precision, and corrected misconceptions without fanfare. Her work was judged in seconds recovered in a dive, in engines that ran when they should have failed, and in the confidence of pilots returning from combat. The men who flew behind her mathematics remembered her not in headlines but in the way their planes performed. The Merlin engines, once fragile under stress, now carried them safely through maneuvers that had cost others lives. Years later, when old Spitfires roll nose-down at airshows, the steady purr of a Merlin is a subtle echo of Shilling’s brass ring—small, exact, and life-saving.