When Male Pilots Feared the B-29 Superfortress, Two Women Took the Controls

National WASP WWII Museum / Facebook

Challenge and Selection

During World War II, the Boeing B‑29 Superfortress stood as one of the most advanced and complex bombers of its time. Designed for high-altitude missions, the aircraft faced early setbacks, with unreliable engines that often caught fire. As male pilots grew wary of flying this massive four-engine plane, one man found an unusual solution. Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets selected two Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), Dora Dougherty Strother and Dorothea “Didi” Moorman, to show that the B‑29 was safe and reliable—by flying it themselves.

By 1944, the B‑29 project teetered on failure due to its engine issues. Male pilots dreaded the bomber’s engines, known for overheating and catching fire. Tibbets believed that if women—who were often seen as less likely to fly military aircraft—could handle the plane, men would follow.

Strother and Moorman had no prior experience with four‑engine bombers. Yet Tibbets trained them in just three days at Eglin Field, Florida. They learned engine control, navigation, and emergency procedures—without being told of the persistent engine fire issues.

Demonstration Tour

Once trained, the two women flew B‑29s labeled “Ladybird” from Alamogordo, New Mexico, to various airfields across the country. They carried male pilots, navigators, and crew chiefs on demonstration flights. Their calm handling—even when an engine caught fire mid-flight—astonished observers.

Their demonstration had immediate effect. Major Harry Shilling noted in a maintenance bulletin that the women had “remarkable takeoffs” and deep knowledge of engines and controls—many male pilots started asking for training from them. However, visibility also faded quickly. Air Staff Major General Barney Giles tearfully ended the tour, stating they were “putting the big football players to shame,” and feared a crash with women aboard would harm morale.

Though brief, the tour had a long effect. After the WASPs demonstrated safe B‑29 operations, male reluctance faded. One pilot, Harry McKeown, wrote to Strother in 1995, saying, “we never had a pilot who didn’t want to fly the B‑29” after that day. Strother later reflected that the bomber was “so well engineered,” and the experience changed attitudes.

Broader WASP Role

The two women pilots were not alone. Over a thousand WASPs completed non‑combat missions—ferrying aircraft, towing targets for anti‑aircraft training, testing planes, and instructing pilots. Dora Strother also flew radio‑controlled drones, target towing, and assisted other pilots on a wide range of aircraft types.

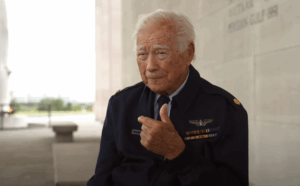

Despite their service, WASPs remained civilians. They did not receive military status until decades later. For Dora Strother, flying the B‑29 was not just duty—it was a statement. She later earned a doctorate in aviation education and helped shape pilot training and aircraft design.

By facing the bomber head‑on, two women flew higher than their planes—they raised hopes and removed barriers for women in aviation and beyond.