The Story of the World’s First Jet Aircraft to Feature a Revolutionary Flying Wing Design

Panzer Archeology / YouTube

A Bold Concept in Wartime Aviation

The aircraft known as the Horten Ho 229 holds a unique place in history as the first jet-powered flying wing. Conceived during the final years of the Second World War, it represented both ambition and desperation. Germany, already facing overwhelming opposition, searched for ways to disrupt its enemies and even strike across the Atlantic. Among these strategies was the idea of developing long-range bombers capable of reaching American cities.

On May 12, 1942, German Air Force leader Hermann Göring announced a competition for what became known as the “America Bomber.” This aircraft needed to carry heavy bombs over 10,000 kilometers at high speed, a goal far beyond the technology of the day. Designs poured in, from radical flying wings to more conventional bombers. While proposals like the futuristic Arado E.555 showed imagination, the final selections focused on designs that seemed more achievable. Yet the concept of the flying wing never disappeared.

The Horton Brothers and Their Vision

Into this environment stepped the Horten brothers, Reimar and Walter. They were not trained engineers but passionate enthusiasts of aviation who had experimented with gliders and radical wing shapes. Their unusual designs eventually drew the attention of the German Air Force, which granted them funds to develop prototypes.

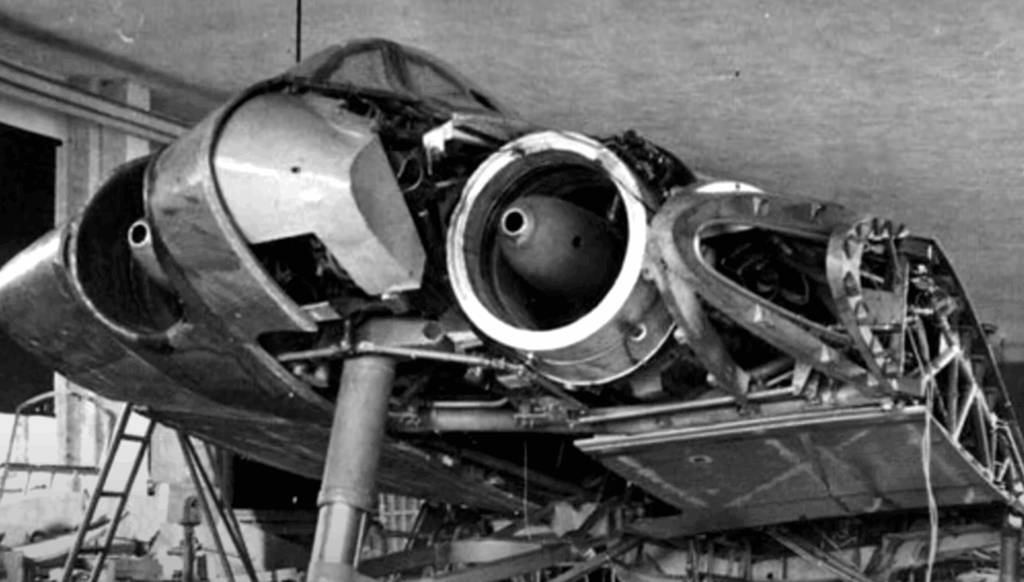

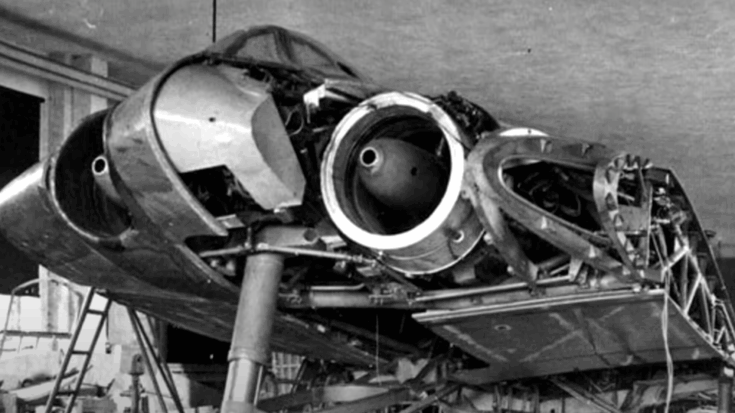

The Ho 229 was built using a combination of steel and wood. It was designed to meet key requirements of the America Bomber project, with a remarkable top speed of over 970 kilometers per hour and a range close to 2,000 kilometers. The aircraft measured 7.5 meters in length with a wingspan of 16.8 meters and could reach altitudes of 16 kilometers. In January 1945, the first prototype achieved flight, making it the world’s first jet aircraft built around a flying wing design.

Innovation and Early Stealth Features

Unlike the earlier Arado concept, the Ho 229 moved beyond paper studies. Its futuristic appearance caused many to speculate about its ability to avoid radar detection. The airframe, made partly of wood, included a mixture of charcoal dust within the glue to absorb radar waves. These choices gave the aircraft qualities that resembled what modern aviation would later call “stealth.”

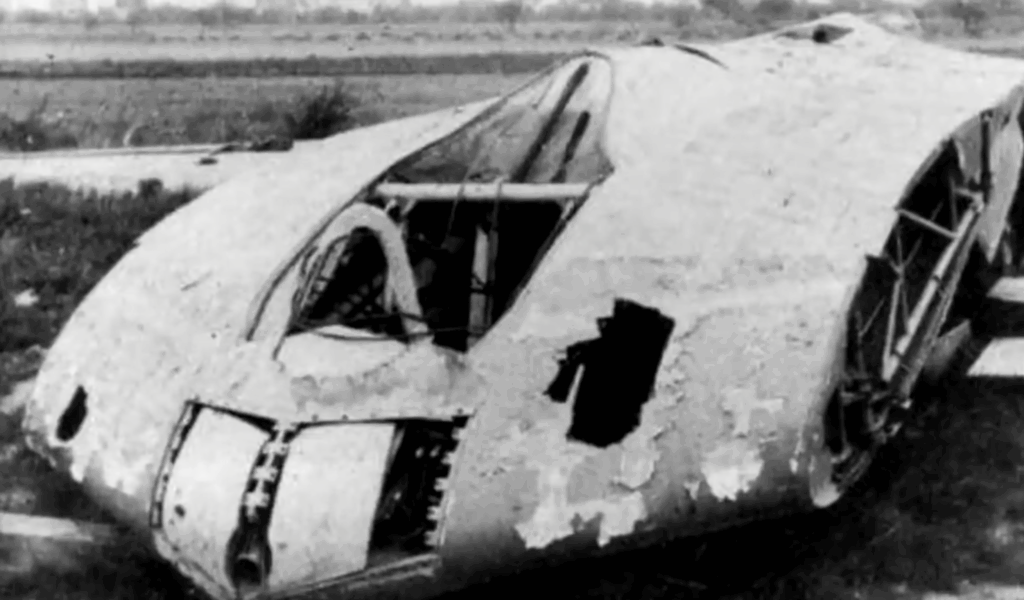

At the time, however, none of these theories could be confirmed. The Ho 229 never reached operational service, and the war ended before it could be tested in combat. Still, its design hinted at ideas far ahead of its time, ideas that would resurface decades later in advanced American aircraft.

Captured and Tested

When the war ended, two Ho 229 prototypes were captured by American forces. These were shipped back for study, allowing engineers to examine the radical construction. Although the aircraft was judged flawed and less practical compared to the flying wing concepts being developed by Jack Northrop in the United States, its unusual design left a lasting impression.

Years later, in 2008 and 2009, Northrop Grumman reconstructed the aircraft to test its capabilities. These studies confirmed what had long been suspected—that the Ho 229 possessed genuine stealth properties. Its radar signature was about 40 percent smaller than conventional fighters of its era. British radar stations, for example, would have detected it from 130 kilometers away, compared to greater distances for other German aircraft. Flying at low altitude, it might have passed unnoticed until it was too late.

A Glimpse of the Future

Although built too late to influence the war, the Ho 229 represented a bold step in aviation. Its construction techniques, materials, and design concepts showed remarkable foresight. The use of wood mixed with charcoal dust, in particular, demonstrated an awareness of radar detection that would not fully shape military aviation until decades later. In this way, the Horten brothers’ creation has often been regarded as a precursor to the American B-2 Spirit stealth bomber developed more than forty years afterward.