The WWII Bomber Designed to Drop Planes Instead of Bombs

Artillery Club / YouTube

A Strange Idea That Actually Worked

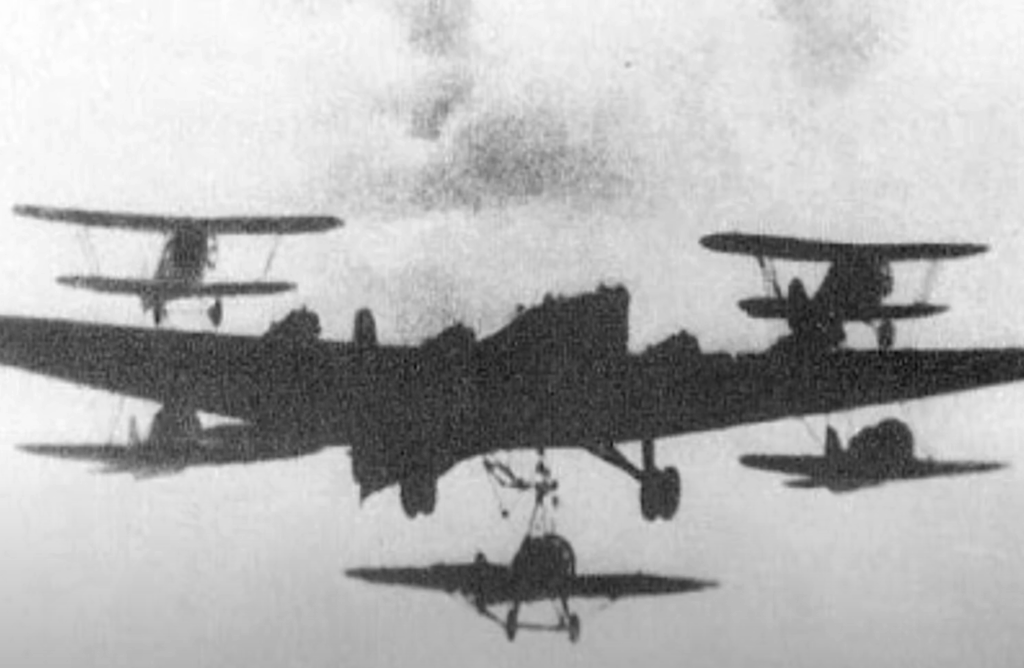

In the early 1930s, when flight was still young and full of imagination, the Soviet Union explored one of the boldest aviation ideas ever attempted — a flying aircraft carrier. It wasn’t science fiction. These were real planes that carried other aircraft into battle, launched them in midair, and even tried to reattach them afterward.

The project, called Zveno, began as an experiment but ended up fighting in World War II. Though only a few were ever built, the Zveno proved that one bomber could carry multiple fighters into deep enemy territory, drop them to strike targets, and turn what seemed impossible into a working combat system.

The Problem of Protecting Bombers

In the 1930s, air power was becoming the backbone of modern warfare. Heavy bombers could fly long distances and carry massive loads of explosives, but they had one major weakness — range. Fighter escorts, which were supposed to protect them, simply couldn’t fly far enough.

When escort fighters ran out of fuel and turned back, bombers had to continue alone, becoming easy targets for enemy interceptors. Engineers tried adding more defensive guns to bombers, but this only made them heavier and slower. It became clear that the problem wasn’t more firepower — it was endurance. That’s when engineer Vladimir Vakhmistrov proposed an unusual idea: instead of fighters trying to follow bombers, what if the bombers carried the fighters themselves?

Building the Flying Mother Ship

Vakhmistrov’s vision was simple but revolutionary. Large bombers could act as “mother ships,” carrying smaller fighters attached above or below their wings. When combat began, the smaller aircraft could detach, fight, and even return to reattach midair if needed.

The Soviets had just the bomber for the job — the Tupolev TB-1, a massive twin-engine aircraft that could lift heavy loads. Engineers experimented by attaching fighters on top of and under its wings, carefully testing which positions wouldn’t interfere with airflow. After many trials, they found that the configuration actually improved lift and stability. Since the fighters’ engines stayed running during flight, they added extra thrust, making the combined aircraft surprisingly efficient.

Early Experiments and Technical Triumphs

Attaching and launching the fighters worked far better than expected. The real challenge came with reattaching them midair — a task that required incredible precision. Vakhmistrov’s team developed a special locking system that allowed the fighters to hook back onto the bomber while flying. Communication between the two aircraft was done through a telephone cable and a set of signal lights, which was groundbreaking for its time.

Even with such progress, the system had practical challenges. Loading the fighters onto the bomber on the ground was exhausting work, often requiring dozens of men pulling ropes to position the planes. It took the intervention of the Soviet government, which provided a tractor, to make testing smoother. By 1932, the idea had become a working prototype called Zveno-1. Over the next years, new versions followed — Zveno-2, Zveno-3, and finally the Zveno-SPB, the most advanced model.

From Prototype to Combat

By 1940, as Europe plunged into war, the Soviets had refined the Zveno-SPB into a true combat platform. It could carry two I-16 fighters, each armed with 250-kilogram bombs. When Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the Zveno was rushed into service.

These aircraft were used in the southern front, particularly over Romania. Regular bombers couldn’t reach deep targets there, but the Zveno could. On its first mission, it dropped fighters loaded with bombs onto enemy oil refineries — targets far beyond the range of any single aircraft. The Romanian defenders didn’t even believe what they saw. They thought the I-16 fighters were defectors because no fighter could normally fly that far.

Success Over the Danube

The most famous operation came in August 1941, when Zveno bombers targeted the King Carol Bridge in Romania, a vital supply route. Conventional Soviet bombers had failed to destroy it before, but this time, the Zveno’s fighters hit it precisely. The bridge was heavily damaged on the first raid and completely destroyed after the second. The attacking crews suffered no losses.

Over the following weeks, the Zveno carried out around thirty missions, striking bridges, docks, and military targets across enemy lines with impressive accuracy. During one engagement, the fighters even shot down two German aircraft that tried to intercept them.

The End of the Flying Carrier

After September 1941, records of the Zveno’s missions disappear. The Soviet Air Force, overwhelmed by retreats and heavy losses, lost most of its experimental aircraft. It’s believed that the remaining Zveno bombers were either destroyed on the ground or abandoned as the front collapsed. By 1942, the concept was retired as newer dive bombers took over.

Still, for a brief moment, the skies over Eastern Europe saw something extraordinary — a bomber that didn’t just drop bombs, but launched entire airplanes into battle.