Why Flying the F4U Corsair Claimed So Many Pilot Lives in WWII

Vintage Stories / YouTube

A Deadly Introduction

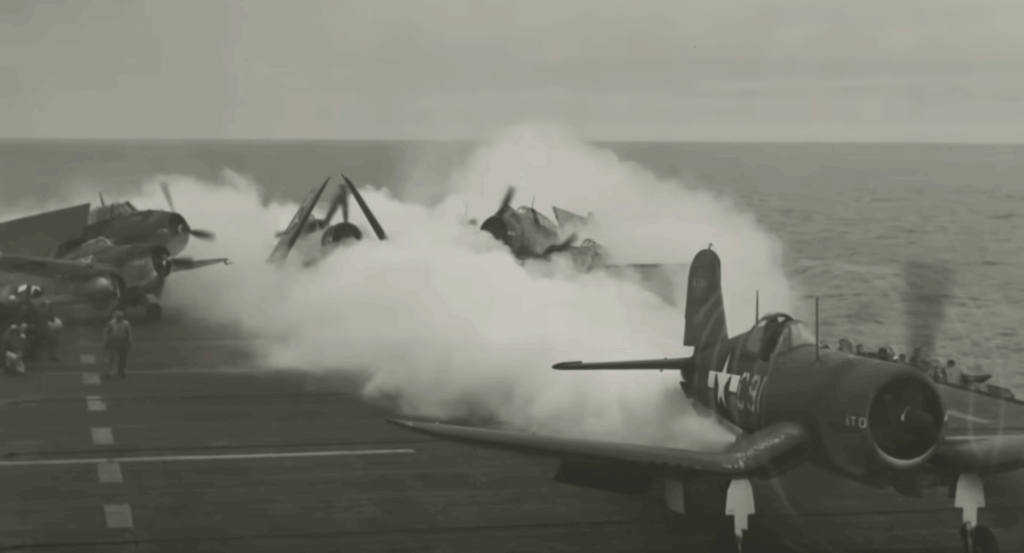

In the early years of the Second World War, the United States Navy welcomed a new fighter that promised unmatched speed. The F4U Corsair, the first American naval aircraft to exceed 400 miles per hour, carried a 2,000-horsepower engine and a huge 13-foot propeller. It looked like the future of air combat, but for many young pilots it became a threat as dangerous as the enemy. Training records from 1942 and 1943 show that nearly 700 American aviators died in accidents involving the Corsair, most during takeoffs and landings rather than in battle.

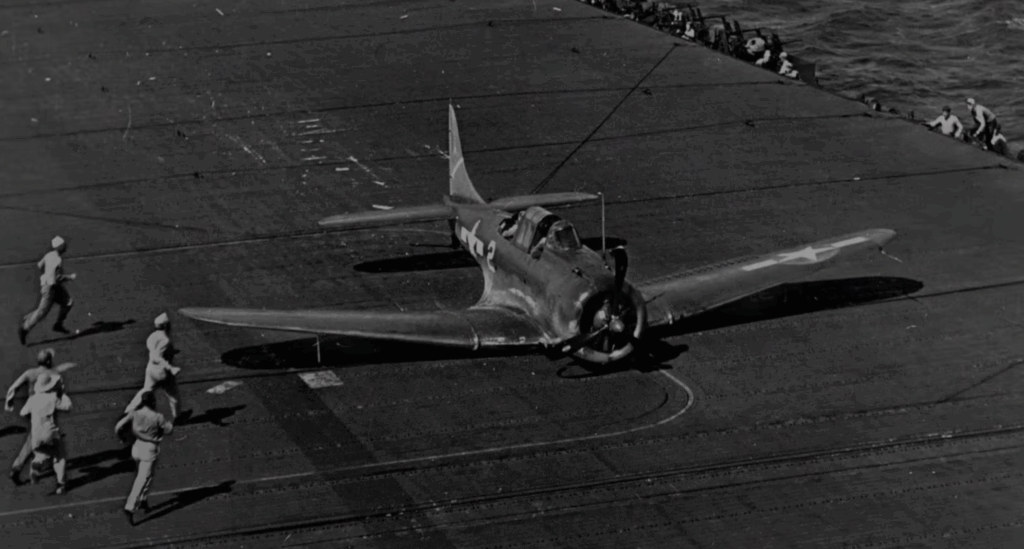

The nickname “Ensign Eliminator” reflected real fear. Rookie pilots fresh from flight school had to solo the Corsair with only a few hours of experience. There were no two-seat trainers, so every mistake happened at full speed. Flight decks echoed with the screech of metal as planes cartwheeled or bounced down the deck. Letters home told of landing blind, depending entirely on hand signals from the landing signal officer while the long nose of the aircraft hid the carrier deck from view.

Design for Speed, Not Ease

The Corsair’s power plant was the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial engine, nearly twice as strong as earlier naval fighters. To use a propeller large enough to harness that power, designers created the now-famous inverted gull wing. This allowed short, sturdy landing gear while giving clearance for the immense blades. Wind-tunnel tests proved the shape worked for speed, but the long nose and heavy torque made the aircraft tricky during slow approaches. The left wing often stalled first, snapping the plane into a sudden roll just as it neared the deck.

Landing gear added to the danger. Built stiff to handle carrier operations, it offered little cushioning. If a pilot struck the deck at the wrong angle, the plane could bounce back into the air and skip uncontrollably. Even skilled aviators sometimes overshot the arresting wires and plunged into the sea.

Solutions from Both Sides of the Atlantic

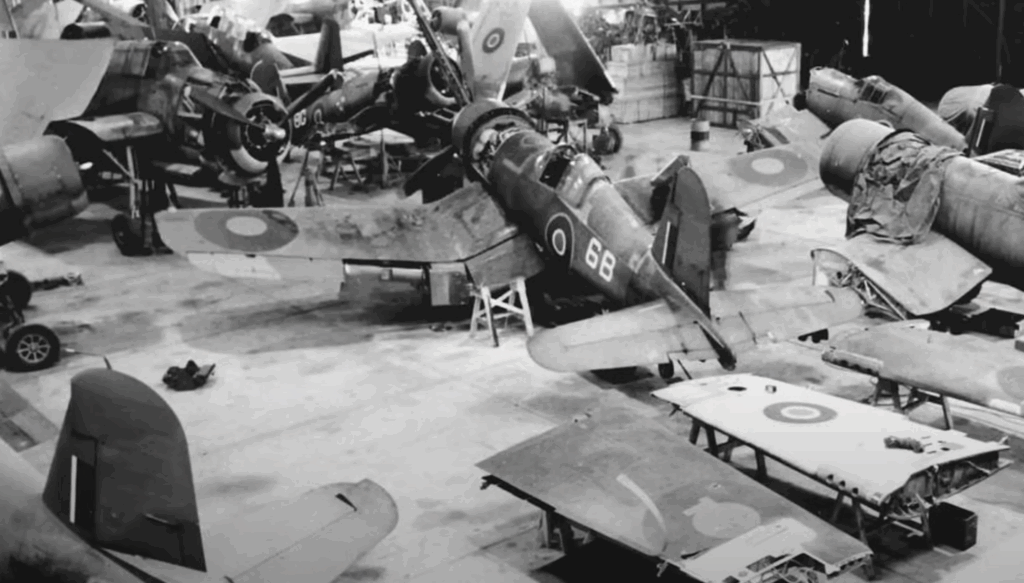

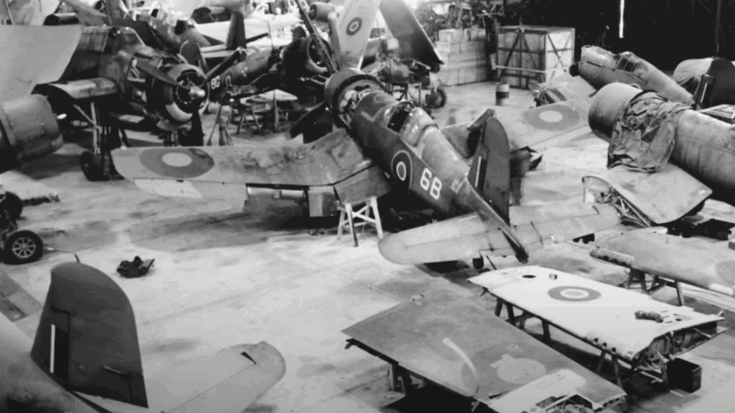

British pilots encountered the same hazards when they received the Corsair in 1943. Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown and his colleagues adjusted their carrier approach, using a gentle curve rather than a straight line so they could keep the deck in sight through the side window. They also clipped eight inches from each wingtip to fit the fighter into tight hangars, a change that unexpectedly improved landing behavior. American engineers meanwhile fitted a small metal strip to the starboard wing’s leading edge to make that wing stall first, preventing the violent left roll. A raised pilot seat and a bulged canopy further improved visibility.

These refinements slowly reduced accident rates. By 1944 the U.S. Navy approved the Corsair for full carrier duty, and newer versions included softer landing struts and the British-inspired improvements.

From Hazard to Dominance

Once pilots mastered its demanding nature, the Corsair proved a fearsome weapon. Marine and Navy squadrons shifted tactics, using high-speed dives and rapid climbs rather than tight turns against Japanese fighters. With six .50-caliber machine guns, and later rockets and bombs, the aircraft excelled as both a fighter and a ground-attack platform. By the war’s end, official records credited the Corsair with destroying more than 2,100 enemy aircraft while losing fewer than 200 in air combat—a kill ratio of about eleven to one.

The F4U Corsair’s early record of deadly training accidents shows how innovation in wartime can outpace preparation. Only through engineering fixes and hard-earned pilot experience did the aircraft change from a dangerous experiment into one of the most effective fighters of the Pacific war.