The Unsung Women Who Piloted 12,000 Planes During WWII

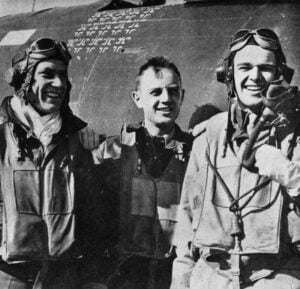

Photo by Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A War Waiting for Pilots

By late 1942, American aircraft factories were producing fighters and bombers faster than anyone could deliver them to the front. Thousands of planes sat idle on the assembly floor while the war raged overseas. Every male pilot ferrying an aircraft across the country meant one fewer available for combat. The problem wasn’t production — it was logistics.

The War Department faced a shortage that threatened to choke off air power before it ever reached Europe or the Pacific. Then Jacqueline Cochran, one of the most skilled civilian pilots in America, walked into a room full of generals with an idea no one wanted to hear: let women fly the planes. Her plan was simple — have civilian women ferry new aircraft from factories to bases so male pilots could focus on combat missions.

Building a Force Nobody Believed In

Cochran’s proposal met immediate resistance. Many officers argued women lacked the strength or technical knowledge to handle powerful military aircraft. Cochran knew better — a P-51 Mustang didn’t require muscle, it required skill. A B-17 Flying Fortress responded to training and precision, not gender. With determination, she secured approval for what became the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASP.

From 1,830 applicants, only 1,074 women earned their wings, matching the same rigorous washout rate as male programs. Their training lasted six months, covering navigation, weather, and emergency procedures. They learned to fly in all conditions and handle every type of aircraft — from small trainers to the newest bombers rolling off the production lines.

Fighting Bias While Flying the Best

Even as the women proved themselves, they faced constant skepticism. Some male pilots doubted they could handle emergencies; others feared for their postwar jobs. The War Department called the program “temporary.” The women were treated as civilians, not military personnel, despite flying military aircraft in military missions.

Their performance soon silenced many critics. Records showed that women pilots matched or even exceeded men in delivery times, safety, and mission success. They flew alone, often without radios or navigators, across unpredictable weather and mountain ranges. They mastered new aircraft with only a few hours of instruction — sometimes none at all.

The Real Test: The Machines Themselves

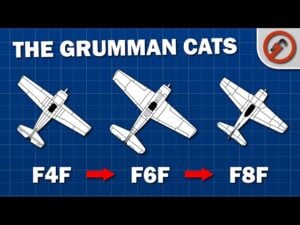

WASP pilots flew 78 different aircraft types. The P-51 Mustang demanded precise handling at high speeds — a small mistake could destroy the plane. The B-17 required managing complex engines and hydraulic systems, all done solo. Even “safe” trainers like the AT-6 Texan could spin out of control if handled incorrectly.

Their missions were dangerous. Ice storms froze controls, engines failed over mountain ranges, and navigation errors could mean disaster. Thirty-eight women died in service, their sacrifices unrecognized at the time. They were buried without military honors because, officially, they weren’t soldiers.

Achievements Hidden in Plain Sight

Despite the risks, their results were extraordinary. Over two years, WASP pilots delivered more than 12,000 aircraft and flew over 60 million miles. They ferried everything from light trainers to the massive B-29 Superfortress, often with only hours of preparation. Their precision reduced delivery times by nearly a third, matching experienced male ferry pilots with full military training.

Their work freed hundreds of male pilots for front-line combat. Analysts estimated that WASP operations increased available combat manpower by 15 percent — a hidden contribution that helped sustain the air war in Europe and the Pacific.

Recognition That Came Too Late

When the war began winding down in 1944, returning male pilots replaced the women. The program was quietly shut down. Records were sealed, benefits denied, and their role nearly erased from history. It wasn’t until 1977 that Congress finally granted them veteran status — 33 years too late for many who had served.

In 2009, surviving WASP members received the Congressional Gold Medal, honoring their courage and skill. Their story remains one of the most overlooked achievements of the war — proof that ability, not gender, defines a pilot.